by Killian Quigley

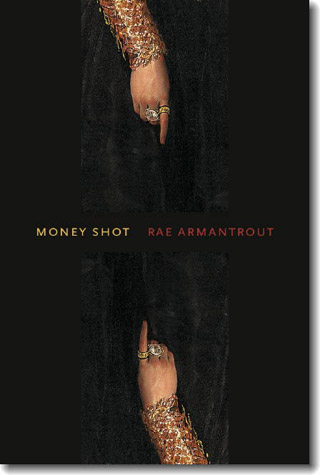

Published by Wesleyan University Press, 2011 | 92 pages

Reviewing Rae Armantrout's work after her last book, Versed (2009), won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award is a decidedly different affair than it might have been, say, four or five years ago. Not that anything has changed radically in her style or content. Her poems are still terse, elliptical fragments. They still interrogate identity, voice, language, politics, sex, media, capital. At their best they still buzz like Emily Dickinson's fly between us and the light of our casual assumptions. Reviewing Armantrout's new work is different now because those awards and the reviews that followed make her the most recent in a line of experimental poets to find her work applauded and more widely circulated by the center, aesthetically speaking, of the poetry community, and, as such, she has also become a cipher for the shifting terrain of contemporary verse. One is obliged to comment.

Armantrout is one of the Language poets, a group of experimental writers that come in East and West Coast flavors. She is of the second stripe, emerging from Berkeley in the 1960s and 70s alongside such writers as Ron Silliman, Carla Harryman, Barret Watten, and Lyn Hejinian. (The group has authored a collective autobiography in ten volumes, The Grand Piano, that makes for a fascinating read.) Their poetry aims to push back against the conventions of language that shape and constrain our lives: the language of commerce, the language of the news media, the language of liberal individualism. Their works are strikingly diverse, from Silliman's mammoth epic of parataxis, The Alphabet, to Hejinian's lyrically disjunctive memoir, My Life. They often emphasize collage and appropriation, fragmentation and repetition in an attempt to estrange language to political ends. Their investment in such procedures can produce an effect not unlike looking at the back of your mother's cross-stitch: the picture is still there, but all the knots and dangling strands let you know this is an emphatically made thing.

The poems of Money Shot tend, like all of Armantrout's work, to be short: short lines, one- or two-line stanzas, terse and epigrammatic (or "meta-epigrammatic," as one blurb would have it). This is not trivial, for the poet or her readers. Such brevity makes her poems more easily assimilable to the model of the short American lyric and is partially responsible, one might assume, for her domestication in such major reviewing outlets as The New Yorker. But their length is also part and parcel of the poet's attention to seams and fissures. A poet like Silliman—perhaps the most notorious poet-blogger and editor of In the American Tree, an anthology of experimental poetry—builds up huge swaths of language, approaching a totality of experience his own aesthetics would seem to resist. Armantrout, by contrast, has never needed more than those interstitial spaces. Her poems are all knots and strands.

Delighting in language that mixes registers within the micro-terrain of her compact stanzas, Armantrout is the practitioner of a particularly American le mot juste. A favorite mode is the single-sentence pivot, and a few examples will give the general sense:

Flipping insouciantly from theogony to design paradigms, from the Gospels to crime drama, these juxtapositions are usually intended to undercut the former in favor of the latter. The effect can be terrifying, if also somewhat slapstick. "Money Talks" shifts suddenly from sex to violence: "On a billboard by the 880, // money admonishes, / "Shut up and play."" The sense of assault perpetrated in these lines is an underlying threat felt across the entire volume. Money is lurid and seductive, playing out bondage scenarios on the internet, but also brutally authoritarian. A system of contracts and coercion hides in the playful language of advertising.The angels are the old godswith a new serviceorientation. ("Fear Not")For I so loved the worldthat I set upmy only sonto be arrested. ("Answer")-Hit the refresh button and this is what you get,money pretendingthat its hands are tied. ("Money Talks")

Thomas Browne, Gerard Manley Hopkins and William Wordsworth all make appearances in Money Shot, and Hopkins in particular is a strangely appropriate presence. His attempt to make language be the material thing it signifies, to break the barrier of mere representation, proves to Armantrout—a poet with an eye for the deceptions of language—a powerful ideal (or perhaps delusion). Wallace Stevens spoke of the "intricate evasions of as," but Armantrout retorts, "Like only goes so far" ("Outage"). The final poem in Money Shot is entitled "Real Article." It concludes:

The day is warm. "The."The title, it appears, was a pun, albeit a serious one. The poet proposes to give us reality, but authenticity as such is a property of language, part of the mobile army of metaphors. It is another variation on Stevens, this time from "The Man on the Dump," who asks, "Where was it one first heard of the truth? The the." A clever but simple repetition of modernism's greatest questioner? Armantrout, in any case, has already admitted to recycling: her poem begins, "Everything I know / is something I've repeated."

Having arrived at the center of contemporary American poetry, Armantrout looks neither more nor less experimental than before. But a close attention to her avant-garde pedigree or its complete effacement are both evasions of a sort. In the meantime, the work itself has become that of a major American voice, whether or not one enjoys putting "voice" in scare-quotes. Armantrout herself warns her readers against any assumptions they bring to her poems: "It rhymes and does not / confirm." Her work is a sustained labor of attention, and Money Shot demands an equal contribution of its admiring readers.

Justin Sider is a PhD candidate in English at Yale University. His poetry has appeared recently or is forthcoming in Boston Review, Bat City Review, and Indiana Review, and his reviews have appeared in Colorado Review and Meridian. He lives in New Haven, CT.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig