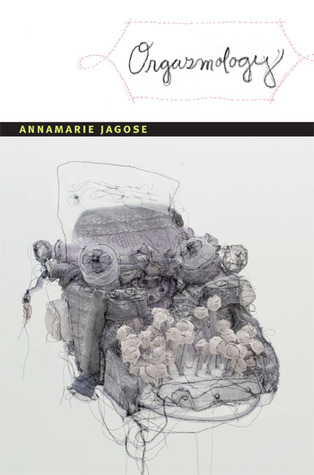

by Katherine Preston

Published by Duke University Press, 2013 | 280 pages

As primitively wild as we might imagine sex to be, it is nonetheless often experienced today through a surprisingly orthodox narrative arc, with orgasm, described by Annamarie Jagose in Orgasmology as “both a sexual and story payoff,” marking the neat conclusion. We see orgasm simplified, for example, in pornography, where orgasm invariably indicates a scene’s ending. We read orgasm as the end goal of sex in a variety of documents on sex including twentieth- and twenty-first century marital advice manuals, sex-positive feminist doctrines that promote orgasm as feminist liberation against masculinist ideals, and theoretical considerations of orgasm by queer theory giants Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze. It is not surprising, therefore, to hear from Jagose that popular media in New Zealand, where Jagose was teaching during her research for this volume, scoffed at her study as unwarranted, presuming orgasm to be too familiarly conclusive to warrant additional treatment. Upon learning Jagose was researching twentieth-century orgasm, the common refrain was “What other kind is there?”, implying that one orgasm shares the same story as any other.

To the contrary, orgasm, for Jagose, is no unified entity with a singular story. Her goal in Orgasmology is to examine orgasm not as the end of sex’s story, but as its beginning, to unsettle “cultural investments in narrative and sexuality” that “constitute” orgasm as “the nonnarratable, that which is incapable of generating any further narrative.” “The best of orgasm,” Jagose contends, “is its multivalent productivity, its availability for being read two, three, many ways.” More than any mere theoretical rethink, reconceptualizing orgasm as multivalent promises to refract the very “selves” of those who experience it into unstable multivalences as well; the extent to which one orgasms is the extent to which one’s sexual self is not stable but precarious.

Orgasmology’s analysis is rooted in a phenomenology of orgasm that argues that modern individuals experience orgasm as paradoxical. Orgasm, Jagose contends, spans binaries that include the “innate and acquired; voluntary and involuntary; mechanistic and psychological; literal and figurative; trivial and precious; social and asocial; modern and postmodern; liberating and regulatory; an index for autonomy and self-actualization as well as for the interpersonal and communal attachment; the epitome and the extinction of erotic pleasure; and indifferent and intrinsic to taxonomic categories of sexual difference and sexual orientation.” In orgasm’s oscillation between terms, in its “slip[s] from under the usual protocols of representation,” in its “insistent and unpredictable switch between registers, not one thing more than another,” it, Jagose writes, “figures less its own essential truths than the contingency and partiality of interpretation, which is itself always perspectival.” Orgasm manifests the modern sexual self, in other words, not as already known, familiar, and stable, but as a corporeal and metaphorical force contingent and partial.

Since orgasm is neither an entity of conclusion nor certainty, but of openness, contest, and ambivalence, so too is the orgasming self. That the sexual self could be ambivalent and multivalent challenges popular notions of personhood since at least the late nineteenth century. Indeed, as Foucault and other have argued, the conception of sexuality as the expression of an authentic and singular identity is a legacy of the late nineteenth century, when sex in legal and medical discourses began to dictate a natural, imperturbable inner truth of human beings. Accompanying this narrative has been the suggestion that the extent to which one orgasms is the extent to which one achieves an authentic sense of self, so tethered is the modern understanding of authentic selfhood to sex.

But, as theorists argue, such “naturalisms” do not express any veritable, authentic, or natural sexual selves, but instead are fabrications meant to delimit sexuality to the service of Western modernity (productivity, efficiency, and standardization, for instance). To accept identities like “heterosexual” or “homosexual” as “natural,” theorists have argued, is to overlook sexuality’s status as culturally manufactured and to accept, rather than to challenge, a model of sexuality that curtails erotic potential. Indeed, much feminist and queer scholarship since Foucault, suspicious of nature and its associated biological determinism, has challenged arguments that ground anything about sex in nature, heralding culture as the shaping force of the sexual.

Jagose is particularly interested in the nature of the mainstream cultural endorsement of orgasm as a biological, natural reflex. Her argument departs from previous critical thought in that, so far, she supports this mainstream view. However, Jagose stresses, biology does not delineate static, singular “norms”, but is instead amorphous, volatile. To think of orgasm as partly a biological entity is for Jagose the furthest thing from asserting orgasm’s simplicity or uniformity. For her, biology is a capricious force of change. To be sure, feminist scholars have shown the ways in which biological discoveries are never outside of conventional narratives about the sexual, and Jagose does not deny this; cultural presumptions about sex mold what we have the capacity to see in biology. But, Jagose insists as well, the body’s physiology itself has the capacity to shape the stories we tell about sexuality.

By way of example, Jagose cites discoveries about the clitoris made by a neurology team led by Helen O’Connell at the Royal Melbourne Hospital in 1998. “Medical mappings . . . since classical and early modern” times, Jagose relates, have considered the clitoris rather than the vagina the orgasming agent of the female sexual body. But O’Connell’s research into the physiology of the clitoris showed that it “is not a minute organ located flat to the pubic bone but a substantial three-dimensional structure extending across the perineal region; that it is closely connected to the urethra and distal vagina;” and that “the cavernous bulbs previously associated with the vagina are more properly part of the clitoral complex.” What had culturally been a “conceptualized . . . opposition” between the clitoris and the vagina, “persistently dividing female erotic capacities against themselves,” is now considered a physiologically multiplex structure that nonetheless offers a coherence, if in multiplicity, to female sexuality that had been denied to it since ancient times.

Jagose’s interdisciplinary archive – spanning science, philosophy, the arts, and media – structurally parallels the multivalence of her research subject and offers exciting contributions to the fields of feminist and queer studies. In chapter 1, Jagose studies twentieth-century marital advice manuals by Marie Stopes, showing how the popular promotion of simultaneous orgasm among married couples manifests perceived shortcomings and incompletions of heterosexual coitus. In chapter 2, Jagose explores what she calls the “double bind” of the sexual as manifested by orgasm, its simultaneous expression of both selfhood and also impersonal structure (urbanization, secularization, industrialization). It is this contradiction, Jagose argues, which provides the conditions of possibility from which modern sexual identity emerges. Chapter 3 argues that sexual reorientation techniques (the medico-scientific attempts to convert homosexual men into heterosexual ones, spanning the late-1950s to the mid-1970s), in their behaviorist bent, counterintuitively underscore “unexpected affinities with queer critical paradigms” of today. Having challenged the so-called objectivity of science and medicine in chapter 3, Jagose critiques modernity’s easy pairing of the visual with objectivity in chapter 4; we have no direct, all-encompassing access to orgasm, but access it only partially through representations or limiting visual cues like faces and ejaculation. After critiquing the fantasy of a fully accessed orgasm, Jagose’s final chapter explores one of orgasm’s most invisible and undocumentable varieties: fake orgasm.

Given Jagose’s commitment to orgasm’s multivalence and its “ability to be read two, three, many ways,” one can argue her study could have benefited from including more non-white, non-bourgeois, and non-able-bodied perspectives on and experiences with orgasm. Scholars of queerness of color, working class queerness, and/or queer disability studies (such as Jose Esteban Muñoz, Scott Herring, and Ellen Samuels) might notice the ways in which the orgasms Jagose examines are overwhelmingly white, middle- to upper-class, and able-bodied. Orgasmology seems to overlook a critical reflexivity on these limitations to its arguments’ applicability. As far as I could tell, Jagose highlights only one non-white sexual subject in her study: Sofia from the film Shortbus (2006). To her credit, Jagose includes a blind woman in her examination of the relationship between orgasm and visual culture, but too quickly moves on. There might be more underrepresented subjects in Jagose’s study, but if so we don’t know it, which some might see as at cross-purposes with her commitment to multivalence.

Jagose’s overlooking of these communities, however, is productive, for it invites other scholars to build from the impressive work she has begun. What Jagose convincingly shows is that approaching orgasm as multivalent is just the beginning. Orgasm has ripple effects: as a site of multi-dimensionality and paradox, orgasm is culturally implicated in – and complicates – ongoing “questions of politics and pleasure, practice and subjectivity, agency and ethics.” Given orgasm’s “talent for spilling beyond its apparently proper confines” of the body, representation, and legibility, “coupled with the widely documented difficulties in apprehending it even at the moment of its literal specification or definition,” orgasm serves as a “rich cultural repositor[y]… for thinking about sex unindentured to sexuality and about sexuality beyond disciplinary paradigms.” Jagose’s commitment to thinking orgasm in terms of a beyond, of elsewheres previously unkown, is compelling, exciting, and inspiring for anyone interested in busting the paradigms, and reinventing the possibilities, of the sexual and indeed the human.

Ben Bagocius is completing his PhD in English literature at Indiana University-Bloomington, and his dissertation examines the ways in which fin-de-siècle science offers vocabularies for literary artists to unsettle axioms of and reinvent the sexual. He received a B.A. in English from Kenyon College in Ohio, an M.F.A. in creative writing from New School University in New York City, and is book review editor of Victorian Studies. Ben is also the 2006 and 2010 U.S. Figure Skating adult Midwestern champion.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig