by Killian Quigley

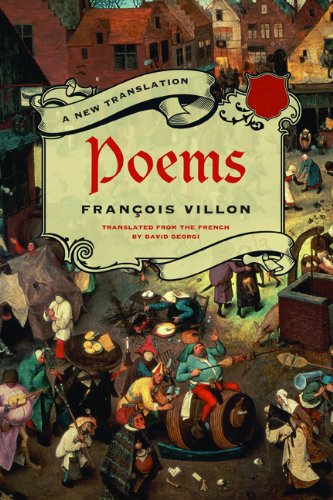

Published by Northwestern University Press, 2013 | 272 pages

In what may have been the last poem he ever wrote, François Villon thanks the justices of the Parlement de Paris for commuting his death sentence to ten years’ banishment from the city. His voice alone cannot convey his gratitude, so he marshals his various parts – his five senses, his heart, his teeth, his liver, lungs, and spleen – to chorus. This is fitting, for they’ve been reprieved from the gibbet’s hideous spoliations, vividly delineated in another short work, “Ballade of the Hanged Men.”

Villon had been condemned to die, in 1462, for his involvement in a fight in which François Ferrebouc, an attaché of the papal delegation to Paris, was killed. It was the last of the poet’s flagrancies, but not necessarily the most outrageous. In June 1455, he injured a priest named Philippe Sermoise in the course of a violent quarrel. After lingering for a day, Sermoise died of his wounds. Around Christmastime the following year, Villon and some pals broke into the Collège de Navarre and robbed the school of five hundred écus. Bodies, burglaries, and empyreal ballades: well over five hundred years on, the original poète maudit continues to mesmerize editors and readers with an uncannily modern poetic voice and a sensational, if sketchy, biography.The rain has soaked us through and washed us cleanand the sun has dried and blackened us.Magpies and crows have cored out our eyes,trimmed our beards and plucked our eyebrows.We never get a moment to rest:this way and that as the wind shifts direction,it swings us at its whim continually,more needled by birds than a darning thimble.(La pluye nous a debuez et lavezEt le souleil decechez et noirciz.Pies, corbeaux nous ont les yeulx cavezEt araché la barbe et les sourcilz.Jamais nul temps nous ne sommez assis:Puis ça, puis la, comment le vent varie,A son plaisir sans cesse nous charie,Plus becquetés d’oiseaux que dez a couldre.)

In David Georgi’s inventive new bilingual edition, Villon’s complete Poems are transfused across the spine from Middle French to cheeky modern English. Special care has been taken to preserve their discomfiting – and irresistible – sense of humor. Georgi’s Villon is sardonic and winking as he skewers our attention to vice, hypocrisy, love, and decay in medieval Paris. Above all, death: here it is final, agonizing, and grotesque. Its aspect is not mollified by sentimentality, religion, or philosophy, but is instead carved in high relief and painted in carnival colors. For some poets, the end of life exists primarily as an abstraction, infinitely malleable to the creative will. Not so Villon, for whom death asserts itself concretely, and pungently. The effect is to disappoint our desire to see in death the symbol of something else: the end of worldly suffering, an invitation to reunite with lost loves, an entrée to some moral truth through which we might better live. What we’re left with is brutally immediate, a living diorama that fixates our senses and refuses to release them from its spell. These poems are horrifying, but they’re edifying, too: they see things as they are, name them, and face them down with bitter, brilliant insolence.

Villon’s greatest and most ambitious composition is the acidly satirical Testament, a hybrid mélange of eight-line, eight-syllable huitain stanzas punctuated by numerous ballades and a smattering of other forms. The French ballade gained its apogee in the fifteenth century, and found its finest artisan in Villon: the Testament’s “Ballade of the Ladies of Times Long Past” and “Ballade of the Women of Paris” are its exemplars. They and the Testament’s other segments may have been intended first to stand alone, then artfully stitched into a grand tissue. This befits so capacious a poem, which unveils Paris – and everyone and everything in it – as decked with ostentation, slapped on to conceal hypocrisy and putrescence.

The Testament presents itself as mock will, doling out backhanded, often fantastical bequests to a litany of legatees, including several of Villon’s real acquaintances. The poet, a “poor peddler of words,” anticipates impending death, and settles his abundant scores by leaving his bar tab to one enemy, a decrepit garden that doesn’t belong to him to another, and so on. Since the late Roman republic, poets have deployed mock wills to illustrate – and lampoon – execrable characters, and character types. The Testament is a pitiless, ribald assault on pretense and priggish moralizing, especially of the religious kind. Villon promises “rich soupes jacobines and flan” to “the Mendicant Friars, / the Devotées, and the Béguines,” and explains, cuttingly:

Toward the end of the Testament, the poet speculates that his epitaph will memorialize him as “a poor impoverished scholar.” We read Villon with one eye trained on the tongue lodged in his cheek, but his relationship to poverty was real – born François de Montcorbier to poor parents, he adopted his nom from Guillaume de Villon, the successful lawyer, chaplain, and academic who had adopted him. Part of the Testament’s achievement is to make poverty visible, and to make it speak. It virulently impugns those who, puffed up by false modesty and sanctimonious asceticism, deprive themselves in pursuit of abstract virtue but lift no fingers to alleviate actual hunger.But it isn’t I who give this giftit comes from every child’s motherand as recompense from God himself,for whom they bear such bitter pains.The good Fathers have to live somehow—especially those living in Paris.If they pleasure all our parish wivesI’m sure they love the husbands too.(Ce ne suis je pas qui leur donneMais de tous enffans sont les meres,Et Dieu, qui ainsi les guerdonne,Pour quy seuffrent peines ameres.Il fault qu’ilz vivent, les beaulx peres,Et mesmement ceulx de Paris.S’ilz font plaisirs a noz commeres,Ilz ayment ainsi les marys.)

But beware plumbing sentiments like these for moral righteousness. Villon’s ingenious trick is to lure his reader, again and again, into a comfortable identification with his seeming sensibility, only to shove us away with a callous jest. The honesty we find so admirable in him brooks no sensitivity. In the Bequests, an earlier experiment in mock will, the poet stoops to crazed meanness:

The Bequests is not a great poem, but its form and preoccupations foreshadow the Testament. You could do worse than to describe each poem as an elaborate inside joke, slyly referencing dissolute persons and wicked histories without ever giving much of the story away. From Villon’s pen, the mock will enacts a delirious cluttering of the world with persons, things, and stories of uncertain meaning, which the world will be left to make sense of after he’s gone. The restless huitain does much to transmit this sense: its ababbcbc structure causes each stanza to fold in on itself in the fifth line. These recurring, half-note key changes keep Villon’s tone and meaning ever on the move. And the Testament is often absurd: to “Montmartre’s mount,” the poet will “give and attach the little peak / that’s known as Mount Valerien, / and furthermore one quarter-year / of the pardon I obtained in Rome.” After several hundred lines’ exposure, one feels a creeping paranoia set in – the joke is coming, to be sure, but one can’t be sure when, and after it arrives, the laughter will be awkward. This is something like the readerly analogue of looking nervously over one’s shoulder.Item, I bequeath to the poorhousemy bed-frame strung with spider websTo those who flop under market stalls,trembling there with faces clenched,wasted, hairy, chilled deep through,their trousers short, their smocks worn thin,frozen, beaten, wracked with flu-a fist in the eye for each.(Item, je lesse aux hospitauxMes chassis tissus d’arignie;Et aux gisans soubz les estaulz,Chacun sur l’eul une grongniee,Trambler a chiere renfrongnee,Megres, velus, et morfondus;Chausses courtes, robe rongnee,Gelez, murdriz, et enfondus.)

Villon’s ludic fabrications and misdirections declare the complexity of his art, and make us read him as something more than a transcriber of immediate sensory experience. His verse makes fifteenth-century Paris all but materialize in front of us, but our view is never anything but kaleidoscopic: the city’s spaces – and its denizens – are always somewhat deranged. This introduces a degree of paradox to some colossally influential critical accounts. Ezra Pound celebrated – and imitated – Villon as a poet of “irrevocable fact” and “grim realism”: “what he sees,” Pound wrote, “he writes.” In its directness, Villon’s poetry signaled, for Pound, a “modern outbreak.” Pound is not alone in this assessment – William Carlos Williams once referred to “an immediacy about [Villon’s poetry] that makes him a contemporary in all our lives.”

Georgi puts the thing more subtly in his excellent paratext, where he adumbrates the life and influence of “one of the first medieval poets to construct a detailed, individualized, psychologically nuanced performance of self.” The Poundian reading runs the risk of intimating that Villon was not a person, or a poet, at all, but was instead some sort of recording device. Ballades impose strenuous metrical and rhythmic demands on their authors, and are, by definition, artful in the extreme. And while it is true that the poetry violently asserts its presentness, it also looks beyond itself, to Roman and Greek mythology, to the Bible, and to French history. The lost women of Villon’s infinitely-anthologized classic, “Ballade of the Ladies of Times Long Past” (“And where is the snow that fell last year?”), range from Thaïs, mistress to Alexander the Great, to Joan of Arc, who was executed by the English around the year of the Villon’s birth. These networks remind us that Villon was a key contributor to the emergent French Renaissance, deeply rooted in his cultural and literary milieux, as well as an inspiring touchstone for Romanticism and the modernist avant-garde.

One has to read these poems out loud, in the Middle French. That needn’t entail understanding all the words – even present-day Francophones tend to read a modernized Villon – but it is imperative if one hopes to encounter their art. For the ballade, as it existed in France in the fifteenth century, had evolved but recently from song, and Villon’s is superb music. Walking from England to Constantinople in the 1930s, Patrick Leigh Fermor remarked that the sounds of London “never pluck at the heart-strings,” but that “Paris, from Villon to Maurice Chevalier and Josephine Baker, never stops.” For Georges Brassens, France’s preeminent twentieth-century singer-songwriter and everyman, Villon was always at close hand; his adaptation of “Ballade of the Ladies of Times Long Past” is magnificent.

In a preface to his rendition of Ovid’s Epistles, John Dryden mulled the rights and responsibilities of translators. “There is,” he explained, “a liberty to be allowed for the expression; neither is it necessary that words and lines should be confined to the measure of their original.” Most important, for Dryden, is the “sense of an author, [which] is to be sacred and inviolable.” In pursuit of Villon’s sense, Georgi has prioritized the preservation of the poems’ tone and voice over their rhyme. This is reasonable, considering the sonic distance between twenty-first century English and fifteenth-century French. The collection takes pains to deliver Villon’s humor, and the translations could never be accused of stuffy fidelity to their source materials. But they are occasionally silly, and clumsily familiar:

But Georgi succeeds more often than he blunders, and he never lets us forget that translation is a phenomenally complicated creative act, and that its potential rewards are sublime. His Anglophone Villon describes “Christmastime, the dead season / when wolves live on wind alone / and people stay inside at home”; after reading that, the holidays will always feel distinctly colder – and more stimulating – than they did before.Two fine and pretty gals they are,who live down in St. Généroux,by St. Julian-de-Vouventes,where Brittany borders Poitou.But I won’t say exactly whereyou’ll find them on a given day ;no, Lordy me, I’m not that dumb !I like to keep my lovin’ secret.(Illes sont tres belles et gentes,Demourant a Saint GenerouPrez Saint Julien de Voventes,Marche de Bretaigne a Poictou.Mais i ne dis proprement ouYquelles passent tous les jours;M’arme ! i ne suy, moy, si treffou!Car i vueil celer mes amours.)

When Villon’s poet enumerates the bits and pieces of his life, and of his city, his main aim is the unsparing exposure of ubiquitous falsehood and pretension. But when he cuts everyone and everything down to size, he is returning them to the human scale. This is the domain of the flesh, of low urges, and of corruption, but also of difficult, salubrious truths. Thus the danse macabre, one of Villon’s favorite motifs, in which humans of all social classes dance arm in arm with death, en route to the grave that will nullify all distinctions between them. Courage to state the facts, and spirit to raise a glass cheekily in their direction – these are the virtues that return us, half a millennium later, to Villon’s music. If we’re honest, we’re sure to keep listening.

And if someone should ask or wonderHow I dare speak ill of Love,this old adage will have to do:a dying man can say what he likes.(Et s’aucun mi’interrogue ou tenteComment d’Amours j’ose mesdire,Ceste parole le contente:Qui meurt, a ses loix de tout dire.)

Killian Quigley is an outsized Irish person and hummus cuisinier ordinarily resident in Nashville, Tennessee, but currently seeking uncomfortable truths at the Sorbonne Nouvelle, in Paris. He is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at Vanderbilt University, where he reads 18th century British and Irish literature.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig