by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Sarabande Books, 2018 | 32 pages

Love may be one of art’s most universal themes, but it is the particulars with which we experience love that make it so precious. Three fingertips trailing across a forearm. The smell of a partner’s hair. A certain joke about a cat and a Russian accent that no one else would understand. In details like these, love transforms. Yet it is these same details––visible from the inside, obscured from the outside––that can also make love so perplexing. One person's devotion, another's obsession. A degree of intimacy that confounds others. A second honeymoon phase in a marriage, reborn after betrayal.

In the short story Puro Amor, Sandra Cisneros takes these liminal spaces between what can be grasped and what can be felt and turns them into her canvas. The author paints a portrait of late-in-life love between husband and wife, crafting a tender story of commitment, creativity, and imperfection. In deft, brushstroke-like prose, Cisneros explores the gaps in our rules and ideas about faithfulness and desire––and reveals the vibrant chaos thrumming at love’s core.

Puro Amor is the story of the Mister and Missus, a reimagining of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in their later years in Coyoacán, Mexico City. The 1983 collection of young adult vignettes A House on Mango Street made Cisneros famous, and here, too, a house is the dominant structure of the story's imaginative world. The Mister and Missus live their eccentric, much-gossiped-about lives at the large and ramshackle Casa Azul, a house that is not just blue, but a "gaudy cobalt" the townspeople call "bizarre." The Missus, ill and frail, no longer leaves Casa Azul, and the story––like her life––is confined to this one place.

Yet this one place is full of life. It is particularly full of the animals the couple have taken in. There are six hairless dogs who "radiat[e] heat like meteorites." There is "a passionate, possessive macaw." There are cats both feral and tame, including one who looks "like a dirty bath mat" and one who says nothing all day but "Me, me, me, me." There is also a "little fawn," tapping through the house with her "ears and nose swallowing air.”

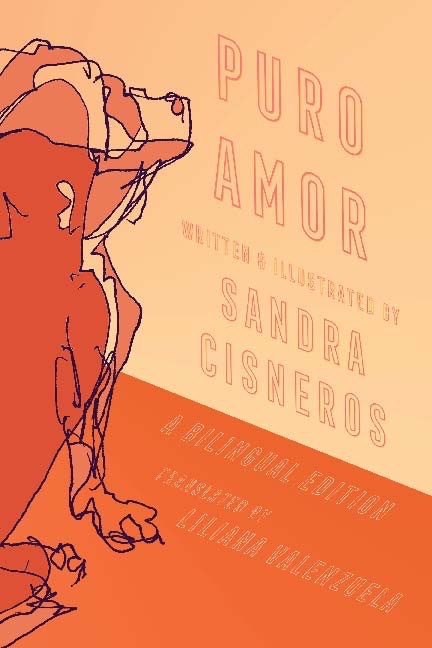

Puro Amor is the first work of fiction for adults that Cisneros has published since her 2002 novel Caramelo. It was originally published in English in 2015 by the Washington Post, and in this edition, appears alongside a Spanish translation by Liliana Valenzuela. The sparse bilingual text is interspersed with line drawings also by Cisneros, a fitting addition to a story where visual beauty plays such a central role. Here, too, the animals' presence is overpowering, with crooked dogs snoozing in the manuscript's upper corners or squatting abstractly over a two-page spread.

The townspeople view these animals as an indulgence. Some find the menagerie of rescues and exotics unhealthy. And perhaps they do place demands on the Missus’s attention. She walks them when she would rather be sleeping. They dirty her bed and commandeer her pillow. They scratch at the Missus's bedroom door, even when she locks it. They ruin "the wood with their urgent devotion." She calls them “troublesome” and tells them: "Whew! What a lot of work it is to love you."

It is a lot of work to love her husband, too. The Missus had to learn to cook from the Mister’s former wife, knowing “if she didn’t, he’d go back there hungry for more than food.” She embroiders him a dishtowel with the words “You Are My Sky.” She takes him a clean change of clothes when he sleeps in his workshop. She arranges flowers in ceramic vases, stacks fruit in high pyramids, and does her own hair in elaborate braids so that when the Mister “raise[s] his eyes from his soup” he will feel happy and at home. When she has time left over, the Missus paints or lacquers a table. The story makes clear that the bulk of her creative energy is spent making life beautiful for her husband.

The townspeople have the same doubts about the Missus and Mister's love that they do about their animals. While the Missus sees this love as “her gift to him,” the townspeople say it's “too much.” They say he’s a “toad” and that he chases after other women. They say he has politicians' mistresses pose nude for his paintings. The townspeople are not entirely wrong. The Mister is “honest[…] about his dishonesties,” but has no wish to change. The Missus, meanwhile, sees all this “only too clearly” and stays with the Mister anyway.

Of love, Cisneros writes, “No matter how much it bites, we enjoy and admire the scars.”

Puro Amor poses many questions. Why do lovers love? How can complete dedication to another be so destructive and so beautiful at the same time? How does a relationship between two passionate lovers become both more and less than it once was? Is love itself a kind of artistic creation––with all the allure and mastery and giving over of oneself this implies?

In her self-portraits, Kahlo turned her own face and body into a symbol, using her aspect as a jumping-off point for exploring pain and illness, femininity and masculinity, Mexican culture and folk art, the connection of the personal to the political. In the years since her death, Kahlo’s face has become so recognizable that the token unibrow and colorful headwear is now something of a shorthand for feminism, queer rights, and artistic flourishing in the face of physical and psychological trauma. Interestingly, Cisneros presents a much less familiar version of “Missus de Rivera” here: one who spends her days tending to her husband and her animals, not particularly concerned with her own artistic legacy. Cisneros also avoids many of the biographical specifics of Kahlo and Rivera’s historical relationship––the age difference, the divorce and remarriage, the politics and who’s-who list of their extramarital lovers. As noted, Cisneros mentions Rivera’s infidelities, but she does not comment on Frida’s, and barely gestures at the latter artist's complex relationship to the expectations of womanhood and hetero-passing marriage in the early-to-mid twentieth century. But this feels less like an oversight and more like an intentional choice, one with which Cisneros echoes Kahlo’s treatment of her own body and identity as a starting place for examining life. As in Kahlo’s art, here too, though the artist may be the subject of this portrait, the work is not ultimately about her.

In Puro Amor, it is not the Mister and Missus that take center stage, but love itself, in all its illogical messiness. And though the story only edges toward answering the questions it poses, here, Cisneros seems to argue––through Kahlo's devotion to Rivera and her peculiar, beloved menagerie of pets––the obvious answer to the question why do lovers love? is the simplest of all: because they can.

Erin Becker is a freelance writer, editor, and translator. She is an MFA candidate at Vermont College of Fine Arts and a graduate of the English and Creative Writing program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig