by Killian Quigley

Published by Pen & Anvil Press, 2019 | 92 pages

“The less said about our professions the better, for we have been most things in our time,” explains Daniel Dravot—soldier, scoundrel, and Freemason—to the narrator of Rudyard Kipling’s “The Man Who Would be King” (1888). Dravot and his colleague Peachey Carnehan will set out for Kafiristan, a remote region of Afghanistan, to follow in the footsteps of Alexander the Great. “We’re not little men,” he notes, “so we’re going away to be kings.” Played sharp and bluff by Sean Connery and Michael Caine, respectively, in John Huston’s film adaptation, these lower-class adventurers live out the romance of British imperialism from underneath. They are its instruments, yes, but also some of its best critics.

When their fantastic ambition falls apart and Peachey returns alone to the narrator’s newspaper office in Lahore, he places the desiccated head of his friend on the desk, an emblem of imperial hubris: “You behold now,” said Carnehan, “the Emperor in his habit as he lived — the King of Kafiristan with his crown upon his head. Poor old Daniel that was a monarch once!” Randall Jarrell wrote that the problem of reading Kipling is that we know too much about him, and his imperialism and jingoism have become commonplaces of his reception. Kipling’s shortcomings are very real, yet fixating on them risks obscuring their counterpoints: Kipling’s tenderness, his bitter and poignant skepticism, animated by an instinctive grasp of the contradictions of empire and his sympathy for figures on the margins of history—the water carriers, colonial functionaries, and Cockney soldiers.

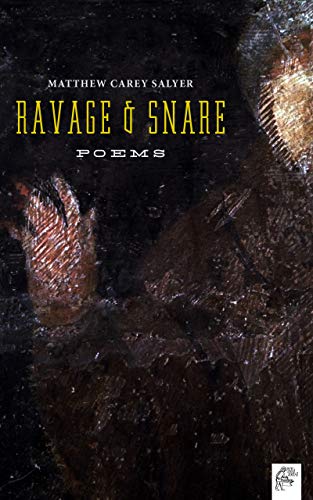

Far away and after, poetry of a different empire, Matthew Carey Salyer’s debut collection Ravage & Snare shares something of this sensibility. These are the poems of a soldier; Salyer teaches at the United States Military Academy at West Point as both doctoral faculty and Army reservist. These striking poems offer, however, neither the grim frontline phenomenology (think Wilfred Owen’s gas-choked trenches) familiar from the history of war poetry nor the moral certainty of the protestor. Instead, Salyer has a keen eye for how a life gets caught up in the machinery of bureaucracy, system, and government.

The poet’s sympathies, like Kipling’s, catch on the pathos of underdog and outcast: a brawling, ear-biting, bird-loving Mike Tyson (who provides one of the book’s epigraphs); boys stick-fighting in the yards of Inwood; a Haitian man trying to buy guns from visiting American soldiers in Aux Cayes. One poem ponders the thoughts of a former Union soldier advising the armies of the Khedive of Egypt and quotes Edward Said on the theatricality of orientalism. Another tracks the mind of a New York state trooper at the end of a slow shift as he finds strange beauty in “the night work” of “a grovel of tweakers / walking on mole hands.” These characters suggest an important refusal to sympathize only with ideal or unobjectionable figures; sympathy need not be the convenient function of virtue or identification.

One of the book’s more affecting dynamics is the interplay of loneliness and family-feeling. “[W]hat good is loneliness if we must share it?” the poet asks. The mood recalls William Carlos Williams’s “Danse Russe,” in which the speaker, a husband and father, wakes before his wife and children to

The intimacy of family life has a remarkable way of drawing out more essential kinds of isolation. Salyer’s poems shuttle back and forth between withdrawal and absorption (in the emotional lives of his daughters; the history of his immigrant family; the imagined life of the father whose absence haunts these pages). In “Silly Old Bear,” the poet speculates on the uses to which his daughters put him: “Girlhood looks so arduous, and it must feel good / to have a killer beside you, // buttoned in bearskin.” In “Do-Right Man,” he imagines a knight set forth from Camelot: “the hero / my kid believes I am at turns and O I swear I do / turn.” That lovely archaic apostrophe, the sudden plea—let me lay claim that, be that person—conjoins devotion and distance: the self forced back on itself, like Williams’s dancer, by the needs of others.dance naked, grotesquelybefore my mirrorwaving my shirt round my headand singing softly to myself:“I am lonely, lonely.I was born to be lonely,I am best so!”

The poems in Ravage & Snare are dense, allusive, witty, and quarrelsome. Salyer’s poetry loves not only the play and texture of words, but also their indexicality, their history. This is a poetry of high artifice, though not in the urbane, laminated style of an Anthony Hecht or James Merrill. Rather, these poems find ancestors in the poetry of Allen Tate, Geoffrey Hill, Derek Walcott, and Les Murray—writers who hold the language in their hands to test the moral weight of words. But the influences are wide-ranging—the obscure, loquacious monologues of Richard Howard; the edge-of-sense soundscapes of Lucie Brock-Broido; and the unsettled aesthetic geographies of Ishion Hutchinson. Hutchinson, in particular, is a kindred spirit—a fellow poet of empire who distrusts the ready-to-hand moral cliché.

Salyer’s lines and phrases have a way of making their own effort tangible. They’re full of densely impacted images, thickened with alliteration, and with the articles boiled off. In these poems, we watch “hares flick oaks’ / great nerves from within / like restless thoughts” (charged monosyllables tripping us up before releasing into the simile). We discover a bride and groom with “dowries arrayed like perfect dioramas / of settled wars” (a beautiful phrase for the wreckage we carry into our relationships). One poem plays at “princess rehearsals” and “doll covens” with the poet’s daughters, while another withdraws into that “inner world where I am / griever and God.” A “Wild Colonial Boy” and “stairwell rat,” the poet builds “experimental architecture for ghosts / two decades before I was born.”

Throughout Ravage & Snare, Salyer’s poems make the private and personal responsible to the institutional and collective. A standout in the volume, “Everything Is Permitted” turns an episode of the original Star Trek into an improbably moving reflection on violence, desire, masculinity, and colonialism. Titled “Red Shirt” when it appeared in Soundings East in 2017, the poem conflates the poet’s ten-year-old self with one of the ubiquitous “redshirts” of Star Trek—the uniformed cannon-fodder that crew the ships of the United Federation of Planets. In the episode “The Man Trap,” Captain Kirk and company encounter a monster that has taken the guise of a beautiful woman (actress Jeanne Bal). Each man in the episode sees her differently; the monster sees them as food—sources of the salt it needs to survive. Eventually the monster is revealed and put down. The poem recounts the young poet’s infatuated response to this “creature-of-the-week”:

The poem offers a touching study of a child’s desire. Careful formal turns hold together and apart the twin perspectives of boy and redshirt: the “rapt” redshirt has literally been transported—beamed down to the rock planet on which he dies as a victim of the monster, but the line-break returns us to the mind of the plot-hungry boy “dying / to see.” The boy’s rapture comes not from a transporter beam but from his own erotic imagination. The context is explicitly colonial: the men of Star Fleet have arrived here like the violent Christian explorers in Elizabeth Bishop’s “Brazil, January 1, 1502,” chasing their fantasies in the forms of native women. The poem doesn’t forgive this desire; the landscape in full of plants “sized like remorse.” When the leading men compare the monster’s death to that of “the last bison,” the analogy seems more callous than thoughtful, and the final sentence—“We four without fault”—ironizes (but does not rebuke) the poet’s sentimental recollection of early desire.Rapt to the rock planet, I was dyingto see the outcome, the death I never didunderstand, at least not clearly at allof ten. The first episode’s “The Man Trap.”To recap, the three appear on the moor.Ruins, as in Canaan. The glade, the nakedball-root flowers, sized like remorse,and aren’t we all born for it, burdensome?Here, on the colonial horizon, the heathwoman’s creature-of-the-week, all glam.Two go down and fine, I’m in love: the camphorloneliness burns between the darling starsis us. She is everything I ever wanted and to herI am tall salt. When she falls, the leads talkas though they’ve killed the last bison. Threein the lazy evening. We four without fault.

Ravage & Snare could be called a difficult book—devoted to a semi-private idiom of wit and erudition, replete with allusions to Edmund Burke and Edward Said, Irish mythology and military history. Yet it’s striking how poems like these can give so generously of the world we share. Geoffrey Hill described difficulty as the compliment that poetry pays to democracy. Salyer would agree, I imagine, though perhaps with an addendum: difficulty and labor are also a part of grace. In Ravage & Snare, we may be glad for poems that let word and world join so joyfully—“consecrating real things to uses.”

Justin A. Sider is an assistant professor English at the University of Oklahoma. He is the author of Parting Words: Victorian Poetry and Public Address (2018). His poetry and reviews have appeared in Boston Review, Colorado Review, Southwest Review, and other journals.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig