by Killian Quigley

Published by Prospecta Press, 2013 | 608 pages

Basil Bunting’s Complete Poems is a slim volume: 150 pages of poems selected by the author, with another 20 or so pages of posthumously collected poems and errata. He grumpily explains his choice in To a Poet who advised me to preserve my fragments and false starts, written when Bunting was 29 (quoted here in full):

Narciss, my numerous cancellations preferslow limpness in the damp dustbins amongst the peeltobacco-ash and ends spittoon lickings litterof labels dry corks breakages and a great dealof miscellaneous garbage picked over bycovetous dustmen and Salvation Army sneaksto one review-rid month’s printed ignominy,the public detection of your decay, that reeks.

In what seems an ostensibly tossed off poem about tossing poems, we nevertheless find themes on display which run through Bunting’s work as a whole—myth, the working class mundane, stoic humor, and just a touch of mordancy. We hear hints in his language of the sonic heights of his later work; we hear its thick, musical beginnings. The alliteration is obvious throughout, but follow the tense, short “I”s in the third line releasing into an “A”: “spittoon lickings litter / of labels.” In the second stanza he loosens the “I”s, they dance around“O”s: “review-rid month’s printed ignominy.”

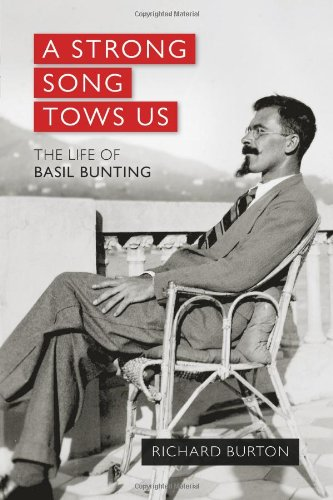

The bile of his poem is directed, principally, at the “printed ignominy” of reviews. This comes partially from the fact that biography and historicist explanations of Bunting’s work were anathema to him; he felt his major poem, Briggflatts, had all the personal history a reader needed. And so Richard Burton’s new biography, A Strong Song Tows Us: The Life of Basil Bunting starts with handwringing: “Is it altogether decent to write a biography of someone who loathed the idea of one, who destroyed all the letters he received and who urged his friends to destroy his own in order to make a project like this as difficult as possible?” Burton, acknowledging the concern, decides to push on.

One worthy goal of Burton’s is simply to raise Bunting’s profile. Bunting was part of the younger generation of modernists who followed Pound, observing his call for a poetry focused on melopoeia, phanopoeia, logopoeia: words charged with music, words casting images, words dancing with intellect. Bunting learned these things from Pound himself. At 24, Bunting moved to Rapallo, the small Italian island and modernist vacation spot: “I climbed a mountain, and on top of the mountain, to my astonishment, Ezra appeared.”

Born in 1900, in Scotswood-on-Tyne, about 8 km from what is now Newcastle in north England—Bunting was educated in a Quaker school where he wrote bad historical fiction, overly rhythmic poetry, and essays on Whitman, Blake, and Poe. In 1981 he recalled his early reading: “by the end of my childhood I was familiar with most of Wordsworth, except for a good deal of “The Prelude.” When I was about the beginning of my teens I read Rossetti’s translations of the early Italian poets. And when I was about 15 I came across Walt Whitman…At a later date I would have to add Horace, in Latin.” Bunting’s literary inclinations and Quaker upbringing instilled a loud pacifism in reaction to the First World War. When he graduated, he was arrested and put in jail for conscientious objection. It was a quick but, nonetheless, isolating experience, one that would mark the commencement of Bunting’s adult life. The impetuous wandering and drunkenness that followed seem more the result of a moral fortitude in response to imprisonment rather than the shenanigans of someone refusing or unable to grow up.

Pound introduced Bunting to Ford Madox Ford, who got him a gig as the copy-editor of the transatlantic review. Bunting would only last for the first issue, but it was an important experience. The review published only 12 issues, but the list of contributors is astonishing—the first two volumes alone featured H.D., F.S. Flint, William Carlos Williams, e e cummings, Pound, Joseph Conrad, John Dos Passos, Jean Rhys, H.G. Wells, T.S. Eliot, Erik Satie, Georges Braque, Gwen John, Man Ray, Pablo Picasso, Nina Hamnett, Constantin Brancusi, Gertrude Stein, Paul Valéry, Havelock Ellis, Djuna Barnes, James Joyce, Jean Cocteau, and Ernest Hemingway. A year later Bunting would be living on Rapallo, studying with Pound. Though he continued to travel through his 20s and 30s—eventually marrying Marian Gray Culver, having three children, and then divorcing (Culver’s decision, based on their constant poverty, and Bunting’s depression in the midst of it).

Two years earlier than To a Poet… Bunting translated the opening of Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things, the Roman poet’s epic about atoms and the Epicurean lifestyle. The translation ends, “…Alma Venus! trim my poetry / with your grace; and give peace to write and read and think.” Key: “trim my poetry.” Bunting, like his friend Louis Zukofsky, saw pruning to be a key element of poetry. The tension and torque of reduced words, no sound or meaning that wasn’t necessary. My favorite example, the first line from his late poem, At Briggflatts meetinghouse: “Boasts time mocks cumber Rome.” The younger English poet Tom Pickard, who was mentored by Bunting, remembers bringing him pages of work to look at over a few pints. Bunting crossed out all but two lines and told him to start over with them.

The main pleasure of reading Bunting is auditory, which he learns partially from musical form; he calls his six longer poems sonatas. Burton’s analysis in A Strong Song Tows Us is especially strong when he examines the role this musical form plays in Bunting’s first major long poem, Villon. Finished when Bunting was 25, the poem, which begins as an homage to the fifteenth century French poet François Villon, is a meditation on death and poetic memory. In response to Villon, Bunting notes that, for the poet, sound is all: “My tongue is a curve in the ear. Vision is lies.” Burton brings together Bunting’s writings on sound with David Gordon’s work on Bunting’s version of the sonata form to elaborate how Bunting, in Villon, maps the structure of the classical form onto his poem, allowing him to vary rhythmic pacing while combining and recombining themes—imagination, beauty, and imprisonment—as a symphony in sonata form overlays melodic content.

Burton argues that Villon is, along with Eliot’s The Waste Land and Pound’s Homage to Sextus Propertius, the “third pillar of the modernist revolution in poetry.” The biographer’s preference comes in response to years of critical dismissal of Bunting for being a poor copy of Pound and Eliot. Certainly, the poem should be more famous. It is formally virtuosic and a window into its age. And yet it is also hard to deny Bunting’s heavy dependence on his predecessors; Pound is always a dominating presence in his work. It’s a charge that followed Bunting throughout his career, even as he came into his own. In a poem he wrote at 49, On the Fly-Leaf of Pound’s Cantos: “These are the Alps. What is there to say about them?” If in Villon, Bunting shows the invisibility of the poet who scratches on something, in this poem it is clearly Pound who is the unknown artist “who knows what the ice will have scraped on the rock it is smoothing.” Bunting, however, vocally rejected the reactionary conservatism of Pound and Eliot. In a letter to Pound: “every anti-semitism, anti-niggerism, anti-moorism, that I can recall in history was base…it is not an arguable question, has not been arguable for at least nineteen centuries.”

World War Two arrived when Bunting was 40, divorced, deeply poor, hardly writing, and he joined the Royal Air Force. His first post was flying defensive hot air balloons over Sheffield but he found the work ridiculous and so, applied for a posting in Persia. In 1930, Bunting found an incomplete French translation of the Shahnameh, the Persian epic by the 10th century poet Hakīm Abu’l-Qāsim Ferdowsī Tūsī Ferdowsi. So struck by the incomplete story, he sought out a full version and learned classical Persian to translate the poem. A selection of his Persian translations, edited by Don Share, was released by Flood Editions in 2012. Based on this knowledge of the language, in September of 1942, Bunting was stationed in Iran, at a base in Ahwaz. After the war, Bunting got a job at the British Embassy in Teheran—“chief of all [British] Political Intelligence in Persia, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, etc.” There he married the fourteen-year-old Sima Alladadian—an age difference that Bunting explains away by its relative normalcy in Persia—and, because of rules forbidding foreign officers from marrying locals, became a correspondent for The Times. It was the beginning of another downturn in his life. Though personally he was in good health—Sima had their first child in 1950—in 1952 Bunting, and all other foreign journalists, were expelled from Iran by Mohammad Mosaddeq. He chased low paying newspaper jobs for the next 15 years, finally ending up at home writing copy in Newcastle.

Late in his life, Bunting’s fame as a poet finally began to grow. In 1964 the 18-year-old Newcastle poet Tom Pickard (on a tip from the American Black Mountain poet Jonathan Williams) showed up at Bunting’s door, was fed Persian caviar from an almost bare cupboard, and given a poem to publish. At the time, Pickard was running an important reading series, library, and press out of the Morden Tower in Newcastle, and Bunting easily fell into his role as an elder. With this youthful energy underneath him, Bunting was able to return to his poetry, writing the long poem his reputation now stands on, Briggflatts.

Burton not only devotes an entire chapter (one of only six) to Briggflatts, but A Strong Song Tows Us is organized according to quotes from each of Briggflatts’ section. This emphasizes the quasi-biographical nature of the poem, and Burton, the dutiful biographer, teases out the most important personal aspect of the poem: Bunting’s youthful relationship with Peggy Greenbank near Briggflatts, the Quaker meetinghouse Bunting visited as a child, and the poem as an act of retrieval. Burton quotes Bunting’s simpler organizational principles: “Commonplaces provide the poem’s structure: spring, summer, autumn, winter of the year and of man’s life, interrupted in the middle and balanced around Alexander’s trip to the limits of the world and its futility, and sealed and signed at the end by a confession of our ignorance.” Don’t think too hard—“All old wives’ chatter, cottage wisdom. No poem is profound.” If Briggflatts isn’t profound, it is because it is a collection of knowledge too precious to be the exclusive province of poets or intellectuals. Briggflatts on love:

We have eaten and loved and the sun is up,we have only to sing before parting:Goodbye, dear love.

And stars:

Furthest, fairest things, stars, free of our humbug,each his own, the longer known the more alone,wrapt in emphatic fire roaring out to a black flue.

As in all of Bunting’s writings, the poem astonishes through sound. For Bunting, sound leads us to the unknown, and in it we may find (enough of) an answer for our existence. Briggflatts’ Coda begins with Burton’s subtitle:

A strong song towsus, long earsick.Blind, we followrain slant, spray flickto fields we do not know.

The poem is 20 pages of concentrated sound and prosaic, concrete ideas. It brought him some fame and friendship with younger poets late in life, and posts on different boards and committees of British poetry (all headache causing). He was able to tour the US for readings a few times, but otherwise he mostly drank scotch and beer at his local, and kept up correspondence with his colleagues. After Briggflatts, true to his stoicism, he wrote only a handful more poems. He died quietly, and without much to his name, in 1985. If he wouldn’t have appreciated Burton’s biography, we can at least do as much for him. For a poet who didn’t write much about himself, it’s good to have a little more.

Devin King is a writer, musician, and teacher working in Chicago, IL. His long poem, “CLOPS,” is out from the Green Lantern Press, Chicago, where he is now the poetry editor. A new chapbook, These Necrotic Ethos Come the Plains, is out from The Holon Press, Chicago. General info available here, and previous MAKE reviews available here, here, and here.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig