by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Open Letter, 2011 | 278 pages

September 16th, 1955. A violent military coup ousts the repressive Peronist government and ushers in a new chapter in Argentine history. Although it ended a decade of censorship and political imprisonment, the ejection of Perón’s populist regime also struck a blow against a newly awakened national consciousness. Those hit hardest by Perón’s downfall were the working class, who for years thrived under Peronist policies of trade unionization, nationalization, and urban development. For them, the coup in the Plaza de Mayo not only signified a new age of political and economic uncertainty, but also a crisis in their nascent national identity.

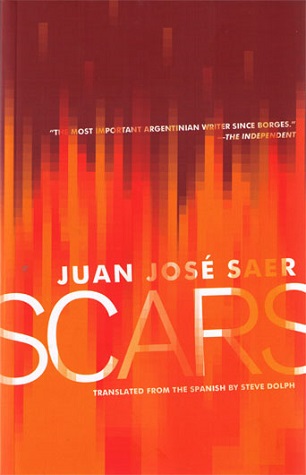

Juan José Saer’s Scars, originally published in 1969, explores, through four interlinked narratives, thirty-nine year old laborer Luis Fiore’s violent shooting of his wife on May 1st, Argentina’s Labor Day. Set in the backdrop of post-Peronist Argentina, the novel at first appears to be a murder mystery. However, as the novel unfolds it gradually becomes evident that the where, why, and how usually found driving the plots of mystery novels are instead empty fixtures here, remnants of a world devoid of meaning.

Telling the story is: Angél, a young courtroom reporter; Sergio, a failed attorney turned gambling addict; Ernesto, a misanthropic judge obsessed with translating Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray; and finally, Fiore, the murderous husband himself. In our introduction to this character, Fiore pleads, “Whoever finds me first should kill me.” Peering into his nightmarish existence, we glimpse how hard rock bottom can be. Fiore’s superficial motive – a fit of rage following an unhappy hunting excursion riddled with his wife’s accusations of cowardice on a day of union worker solidarity – belies a deeper sense of existential despair. To the extent that each of the four narratives shares in this hopelessness, they are found to be equally involved, if not equally complicit, in the forces that finally push Fiore to the brink.

As the title suggests, the four narrators struggle to cope with the scars left in the wake of the personal and national identity crises suffered in the wake of political upheaval. Angél, Sergio, Ernesto and Fiore are all estranged from human conscience in a world perpetually enveloped in suffocating, drab ennui. Ernesto, who by day misidentifies people as gorillas and by night is terrorized by the inevitable return of a crushing depression, describes the novel’s hellish existential terror in a hauntingly captivating line:

The sun is coming up, but the wet fog surrounds the car so closely that all I can see is the inert body of the car and the slowly drifting whitish masses that have erased the waterfront, if there really is a waterfront, and which completely obscure my vision, if – beyond the fog – there really is anything for my eyes to see.Throughout Scars the four narrators struggle desperately to find meaning in a perceptibly meaningless world.

Saer masterfully interweaves personal disillusionment with the shattered ethos of a broken nation: Sergio unwittingly participates in a trade union rally the day of his wedding, which, incidentally, falls on the day of Perón’s coup. His haplessness lands him in jail. After waiting two years for his release, his newly wed wife inadvertently poisons herself in a failed plea for attention. This interlinking between personal tragedy and national tragedy is reminiscent of works like Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children or Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. And yet here the technique shifts the work outside the literary inheritance of magical realism to a place instead somewhere between Dostoyevsky’s literary realism and Sartre’s existentialism. Although often described as the successor of fellow Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, Saer, in this regard, departs from the fantastical to confront the grim everyday reality of political instability, demonstrating how we all may find ourselves a little bit sociopathic should the very seams of society ever rip open.

Although each of the four narratives describe the same sequence of events from different perspectives, each could stand alone as a vignette describing a disjointed whole. Saer’s work could thus be read as an instance of Argentine high modernism with the narrative complexity of Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury or Joyce’s Ulysses. Or, conversely, Scars sometimes reads like four interrelated short stories that lack the narrative cohesion to become the novel it aspires to be, but accordingly demonstrate the fragmentary nature of Argentine political consciousness.

What links these four stories is not just the permeating sense of hopelessness, but also the faintest moments of dry humor that punctuate their telling, particularly the jabs at literary high culture. Ernesto, when he is not gambling away his life savings, pens essays with titles such as Professor Nietzsche and Clark Kent, Tarzan of the Apes: A Theory of the Noble Savage, and The Ideological Evolution of Mickey Mouse. Saer’s irreverence towards the same authors that he is most influenced by (Ernesto dismisses Dostoevsky’s The Gambler as mostly a “waste of time” for not discussing any actual gambling games) demonstrates a metafictional playfulness about genre and literature that cuts away at some of the otherwise overwhelming gloom and doom.

Saer’s description of the aftermath of Perón’s exile – through the personal tragedies of Scars’s four characters – and his depiction of the subsequent death of a nation’s spirit are significant achievements. Whenever Scars seems on the verge of becoming too heavy-handed, Saer pulls us back with his dry wit and self-deprecating humor, without ever making light of one of the darker chapters in Argentine history. Ultimately, it is the coupling of levity and sorrow, hope and despair, that transports Scars from its generic conventions as a post-war murder mystery novel to an insightful, even profound commentary on the human condition.

Allen Zhang is a PhD candidate and Mellon fellow in the English Department at the University of California Los Angeles, specializing in postcolonial literature, speculative fiction, and the digital humanities. He was the recipient of the Arthur Feinstein award at Dartmouth College for his work on Chicana poet Gloria Anzaldúa.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig