by Katherine Preston

Published by Liveright, 2014 | 336 pages

When he came wholly forth I took him up in my hands and bent over and smelled the black, glistening fur of his head, as empty space must have bent over the newborn planet and smelled the grasslands and the ferns. -- Galway Kinnell

A human head. No other body part—an electrifyingly herniated disc, a lover’s member, nothing—has ever compelled my focus with such sheer animal intensity as the head of my child. It took me a good two years before I could palm that small skull without a visceral flash of its emergence. Diameter versus aperture: truly, the part that most distinguishes us—blushes, tears, manipulation, calculation, apperception, abstraction, rhetoric, art—evolved right to edge of our common mothers' bones. Bones don't stretch.

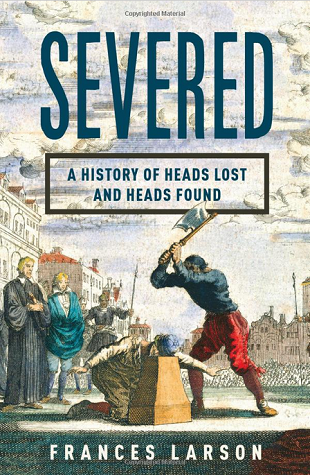

Cranial sacrosanctity, however, is not the concern of Severed: A History of Heads Lost and Heads Found, the latest popular account out from anthropologist Frances Larson. Instead, it explores what happens when our cognitive apparatuses are severed from their respective persons and used as things. Heads in Severed are dead, objectified, sold, commissioned, manipulated, preserved. A series of thematically constellated anecdotes (e.g., “shrunken heads,” “deposed heads,” “dissected heads”), the book has the effect—sordid, arresting, pleasantly unpleasant and unpleasantly unpleasant—of a torture museum: immersed in its darkness, the human body entire comes to seem as a very vulnerable thing indeed.

The neck, for example. In Larson’s telling the neck takes on a tenuousness appearance. As the stalk of a dandelion invites plucking, so too it seems from an analysis of history – most recently evidenced by the gruesome string of recent videos released by ISIS – that the distinct thinness of our necks invites decapitation. Other mammals don’t have big heads on necks so thin and unmuscled. Massage your neck: one can feel the clear contours of its vertebrae, nodes, tubes. Other mammals don’t lend themselves to easy decapitation. Try chopping off the head of a bear (or a lion, for that matter, as we recently learned was done in a game hunter's killing and decapitation of Cecil, a Southwest African lion who lived in Hwange National Park in Matabeleland North, Zimbabwe).

Not that a human head is by any means easy to sever. Larson provides plenty of evidence as to the difficulty of the task, including accounts of ax-men requiring three, four, even five strokes. From pre-guillotine seventeenth-century France, Comte de Lally (five strokes) is one unfortunate example of the Poorly Excecuted Club. Across the Channel, Mary, Queen of Scots got a blow to the head, a blow to the neck, some sawing, and only then a final axe-blade mercy.

Larson also details the significant force required to separate brains from skulls in the dissecting room: “The dissector must hold [the brain] steady within its cramped, dark chamber while the spinal cord is cut below, as well as the many arteries and nerves that attach it to the body.” After the cutting, the dissector grips the brain firmly in hand and dislodges it by physically tearing through the remaining attached tissue.

Janus-face to the technical difficulties of decapitating a body is the ease with which markets develop around the trafficking of human skulls as spectacle, specimen, collection. Severed heads have their own—granted material—afterlives. We see European colonists, for example, selecting heads of live Maori slaves to be tattooed and then cut off for use as souvenirs. Larson describes the necessity of cleaning skulls so as to prevent stench and other fleshy unpleasantries. Across the Pacific theater of WWII, American soldiers "souvenir hunted" and "field stripped," weighing the ease of dogtags and gold teeth against the prestige of body parts and skulls. They enjoyed mixed success with their various head-defleshing and bone-polishing techniques; ants, for instance, did not work quickly enough before the stench became unbearable. Hawaiian customs agents are known to have found at least two rotting heads in GI's luggage. As many as 60 percent of skulls were decapitated from some Pacific Islands, and while officials issued stern warnings, the fact remains that "Skulls were hung from bulletin boards and lashed to the front of US tanks and truck cabs as macabre mascots."

American collectors sometimes continued to meddle with the resulting trophies in the years, and decades, to follow. Larson documents how one Japanese soldier’s skull, which floated around suburban America for decades after the war, was wired to operate as a Halloween lamp. Elsewhere, Larson introduces us to the Victorian adventurer who paid “African soldiers to murder, dismember and eat a girl while he watched.” (The price? Six handkerchiefs.) As in this example, Larson ventures freely at times outside of a strict focus on severed heads—presumably under the assumption that these broader anecdotes illustrate larger ideas about how dehumanization and objectification operates.

The subtitle of the book labels it as a “history.” It isn’t. In offering the reader anecdotes from a potpourri of Western historical atrocities, Larson’s text gives many colorful examples of human cruelty. What is fails to do, however, is give any insight as to how to understand the gruesome practices it documents. This is especially frustrating as a penetrating analysis of the nature of just this sort of violence is already available. Philosopher Michel Foucault opens his great work Discipline and Punish with the vivid and excruciating scene of a man being drawn and quartered. His limbs are tied to four horses. The horses are roused into action by an explosion or some other agitation. Torture here is read as a means to ensure societal control via the public display of the king’s power. Severed resembles a Discipline and Punish that never gets beyond the drawing and quartering.

The small child whose skull I bore once accompanied me to the subterranean bone church of Kunta Kora, Czech Republic. In Baroque horror vaccui, the bones of fifty thousand skeletons ornamented every wall, every surface, the altar, the chandeliers. The child, too young to be afraid, tottered ahead alone. Above her hung the skulls of children. Larson’s catalogue gives us, in our thanatos-phobic modernity, occasion to look into the gaping eyes of the death’s head. Larson’s volume makes visible the abyss that is within us. Memento mori, certainly. And yet what I remember most clearly about that bone crypt was that when my child finally turned back around to look for me, it was to wave and smile.

Newly repatriated from Vienna, Austria, Meredith Castile lives in Palo Alto, California. She works in literature at Stanford and in educational publishing in Silicon Valley. She is the author of the cultural studies book Driver’s License (Bloomsbury, 2015) and numerous reviews and articles.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig