by Angela Moran

Published by Oxford University Press, 2010 | 259 pages

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop is obsolete. Visits to the Broadcasting Corporation’s Maida Vale Studios in West London scarcely reveal a groundbreaking electronic music factory these days. Rather, since 1999, when reel-to-reel tape recorders, analogue synthesizers and voltage-control amplifiers were replaced by chic suede armchairs, projector screens and coloured uplighting, the Workshop’s historic site has survived in a new guise: it is now the main recording studio for BBC television’s live weekly film review show. The advent of the personal computer and the increased availability of inexpensive but high quality digital recorders in the last decades of the twentieth century brought to an end the then unprofitable Radiophonic Workshop after some forty years of service to British broadcasts. Louis Niebur, however, in Special Sound, ultimately stresses the insignificance of the physical Workshop’s disappearance. For Niebur, the Radiophonic Workshop continues to survive, no longer in rooms 11 and 12 at Maida Vale admittedly, but in the sounds and semiotics of the multiplicity of electronic musics that have since spawned in its wake and influence. In Special Sound Niebur distinguishes the Radiophonic Workshop from simultaneous developments in music across Europe and America and positions it at the forefront of a uniquely British populist modernism.

Special Sound is a celebration. Niebur – whose own journey with the publication began as a doctoral thesis – situates the Workshop historically within the need felt for a specifically English brand of experimental music in the mid-twentieth century, in answer to the two burgeoning avant-garde sound centres in Paris and Cologne. The Radiophonic Workshop opened in 1958 after the lobbying of BBC studio managers Daphne Oram and Desmond Briscoe who (inspired by their French peers) sought permanent accommodation for innovative sound design, based on tape manipulation and ‘musique concrete’ (literally ‘concrete music’, the term coined by Pierre Schaeffer in 1948 to describe the then new technique of musical composition which involved the making of sound collages of distorted recorded music via the cutting and splicing of magnetic tape). The Workshop’s reputation, ranks and recording equipment rapidly increased as it complemented pioneering television and radio programming with original soundtrack composition. On closing in March 1998, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop had secured its international reputation as a principal electronic studio of the twentieth century.

With a superficially-linear narrative of reminiscence, Special Sound unobtrusively interacts with theories and issues at the forefront of contemporary musicological debate. Uppermost is Niebur’s challenge to the reader to reconsider just what constitutes music. To all intents and purposes, the ‘special sound’ of the Radiophonic Workshop blurred tonal music and synthetic effects. Hence internal tussles ensued between the BBC’s Drama and Music departments regarding ultimate responsibility. At a time when mass migration forced post-War Britain to negotiate its own identity – when the government assessed arrivals from Ireland and former colonies as ‘neither subject nor alien’ - the national broadcasting corporation mirrored these circumstances with the ambiguous rhetoric of its new audio hybrid, deemed ‘neither music nor sound effect’.

Niebur does not abandon us to our mulling. He makes, for instance, a convincing case for the growth of synthesised tonal music directly from the apparent non-music composed in the Radiophonic Workshop. Highlighting the BBC children’s television series, Look and Read, from the early 1970s, Niebur heralds a previously unheard harmonic sound that would leave the confines of Maida Vale as a new musical genre when its audience came of age. Look and Read, claims Niebur, has a soundtrack that reverberates in the electro-acoustic songs of the late seventies and early eighties made popular by the likes of Kraftwerk, Kate Bush and Mike Oldfield. Niebur discusses Look and Read in terms of dates of broadcast, nature of show and intended audience – a Gramscian approach that engages with the notion of cultural articulation between producer and consumer (Stuart Hall and Keith Negus have found this a relevant model for understanding the music industry). By explaining who was creating and who was watching certain BBC broadcasts at certain times, Niebur substantiates his claim that an entire musical fashion spread from the Radiophonic Workshop, situating their special sounds as a cultural intermediary for British society throughout the second half of the twentieth century.

Sociology and cultural studies are not the only forays outside the central story of Special Sound. Niebur makes the relevance of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop to an entire field of film music theory quite explicit, drawing on Michel Chion and Claudia Gorbman, in relating the ideas of ‘diegetic’ and ‘acousmatic’ music to his original study – these words distinguishing sounds whose source is seen by the audience (an orchestra playing on screen for example) and sounds providing a background atmosphere. Television references (also accessed on OUP’s companion website) prove that the Radiophonic Workshop was never strictly radiophonic. Indeed Niebur claims that the Workshop played a significant role in the success of science fiction on British television; and he goes farther, expanding his topic into the wider context of visual soundtrack analysis. The film theorist James Buhler’s championing of a soundscape combining musical scores, sound effects and spoken dialogue leaps to mind when reading of the BBC’s difficulties in defining those Workshop compositions as ‘music’, for example.

By prioritising the value of people, place, layout and studio design, Niebur raises a most pertinent academic enquiry. Echoing the ideas of French historian Pierre Nora, Niebur inconspicuously separates the realms of history and memory, such that, whilst the former is ostensibly the business of Special Sound – the property of a sequential account of an extinct music studio – the latter continues to be embodied in recollections about the venue, about the people involved and about social and musical attitudes. In short, Niebur implies that the compositions of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop are not simply those very real audible examples described, analysed and made privy online, but they are also understood as the space, equipment and interactions of the scene of their creation.

Despite an exhaustive tour inside the Radiophonic Workshop, Niebur’s is essentially a peripheral view that maps Britain onto wider national and international music movements. An interesting area of expansion would consider the more parochial ideologies and concerns at an increasingly self-conscious BBC from the 1950s. After all, the Radiophonic Workshop came into being at the same time as a new BBC series, the Radio Ballads, deemed to require strict censorship on account of their creation by known Communist-sympathisers. Intensified rules and strict regulations must have affected all at BBC Entertainment (encompassing the drama and features divisions) during this time, and surely hampered progress in the Radiophonic Workshop’s exploration of new territory. Niebur does not consider such concurrent projects within the BBC, although his is a trajectory from the hallowed halls of a 1950s electronic recording studio to a contemporary communal era.

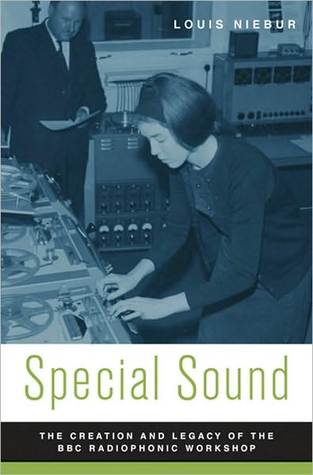

With Special Sound, Louis Niebur achieves a remarkable feat in subtly allying the private concept and design of a bygone BBC Radiophonic Workshop – from its inception, the Workshop implemented a largely closed-door policy to outside composers – with active political, social and academic debates. Niebur presents a gentle, nostalgic veneer to Special Sound’s theorising, making the work both accessible for the general reader and analytical enough for the specialist. Comprised of erudite musical analyses and a wealth of photographs and television stills, soundtrack cues, logbooks and transcriptions peppering his prose, and providing insights into not only the historical manifestations of the Radiophonic Workshop (on screen and radio), but also into the contemporary, post-Workshop translations of its compositions in the digital age – Special Sound is married to a website that makes available online many of the visual and aural clips to which it refers, although cross-referenced numbers for the Orpheus radio examples are slightly mismatched – Special Sound is a trip down memory lane for the BBC enthusiast; a unified lucid investigation for the scholar; and a museum of materials, data and analyses for all who applaud a living legacy. The Workshop is dead. Long live the workshop.

Angela Moran has recently completed a PhD in Music at the University of Cambridge. Her thesis is an urban ethnomusicological study concerned with the development of Irish music by diasporic communities. Angela’s other research interests include popular music studies, film-music theory and gendered musicology. She is also a competent performer on piano, viola and fiddle.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig