by Killian Quigley

Published by Coffee House Press, 2018 | pages

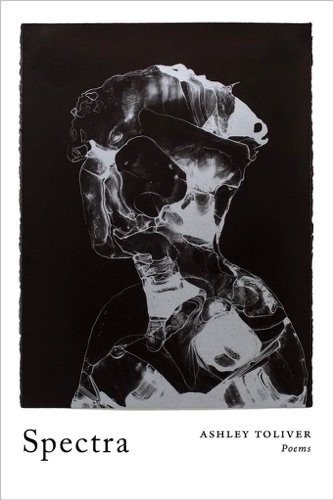

A human profile appears on the cover of Ashely Toliver’s Spectra, but rather than the features of a particular face, the surface of this form evokes lunar craters, daguerreotype photography, a CAT scan, or a specter. And indeed, to encounter Spectra is to be disoriented and unsure of what you see. Ambiguous and fragmentary in form, the book is meditative and introspective rather than explicit or explanatory. These textural poems conjure an environment, an atmosphere, or perhaps a dreamscape. It is as if, in the words of Spectra itself, Toliver is “purposely fraying an architecture you entered by looking,” to help us discover something “beyond…beyond…beyond the bridge lit / inside the mind.”

Often written in address to a “you” or in epistolary form, Toliver’s dreamscapes blur the boundaries of a self in relation to others—a husband, a child, a tumor, a natural environment. Her language flows and bursts as it blurs interiority and exteriority. Spectra was occasioned partly by Toliver’s experience of the unexpected pregnancy with and birth of her daughter, as well as the discovery and removal of a blinding tumor in her pituitary gland shortly thereafter. While these experiences clearly inform her work, the book also exceeds this personal context. A student of Claudia Rankine and C.D. Wright, and affiliated with Cave Canem, a collective dedicated to supporting the voices of African American poets, Toliver offers nuanced, socio-politically invested, and formally innovative poetry. While “spectra” is etymologically related to specters or the spectral, the word is actually the plural form of “spectrum,” and Toliver explores questions of what it would mean to recast the subject-object, self-other, internal-external relationships that define our perception of the world into gradients of myriad possibilities. Spectra gestures toward such radical reorientations of human perception as it expresses and transverses the (in)visible, the (im)measurable, and the (im)material.

Toliver’s epigraphic poem, “Kinesis,” introduces the book’s interest in the ways life and material exceed and defy modern logics of categorization and explanation. As the “globe is cross-hatched dark blue,” we can recognize categorization created through measurement as a basic structure of human perception—a horizon or “tent frame.” But the first lines of Toliver’s poem reveal the rationality we expect from categorization to be an illusion: “The specialist says we can classify species / by measuring height with our hands: / All but the smallest flamingos must stand / eight palm-lengths from the earth.” Here a specialist’s categorization reduces an entire species to a single, variable, imprecise, and human measurement. That the smallest flamingos escape this logic of categorization only undermines it further. “Kinesis” goes on to expose the subjective dimension of seemingly objective categorization, and expose the limitations of human perception in the description of natural events. The poem shifts from the anthropocentric, scientific perspective of its line “we are watching an ocean,” to grant the ocean itself agency as it asks “Can we say this is a continent, oceaning?” Yet the poem remains ambiguously invested as this shift appears only in question form – can we?

The consequences of ignoring or denying the subjective, human element in categorization and the attendant perception of events as determinate and inevitably sequential intensify as we move to the poem’s end. Like the fire that moves in the poem’s penultimate stanza “from the field / to the tree to the house in succession,” so too does the final stanza’s mother – who undresses her children before drowning them – reveal a violence in logical systems of progression through categories or stages. The ending of “Kinesis” offers a critique of the consequences of a humanity convinced of the inevitability of progress, and divested of a sense of human responsibility. While the poem does not explicitly racialize the mother or her children, we might remember that the categorical logic of racialization can make living impossible for those racialized, and drive them to ‘illogical’ conclusions. The force of this poem’s final scene ultimately resides in the realization that no one will intervene even if they bear witness to injustice or distress; no one stops the spiral of violence, be it contained in the intimacy of infanticide or the felt remoteness of planetary change.

Spectra expands and exceeds the questions raised in “Kinesis” across its three sections. Toliver’s language is evocative, halting lucidity shot through with arresting intensities. “Housekeeping,” the volume’s first section, is comprised of prose poems that abstractly portray a marriage through descriptions of defamiliarized natural environments. Making no reference to domestic chores, “Housekeeping” seems most interested in strategies of perseverance and preservation. Epistolary address in poems that begin “Dear night possessor” and “Dear stone fruit” evoke the speaker’s exhausted, unreciprocated, yet persistent attempt to make connection, to simply communicate with an other. Most scenes in this section occur at night, asking us to consider what can be seen, or perhaps simply known, in the dark, as well as what is seen in man-made light. As “light fractures in frame,” the poems meditate on the limitations of representation—which must always imply a frame, and therefore be partial or fragmentary, as Toliver’s poems themselves are.

These scenes describe movement, attachment, and arrangement, calling us to contemplate impermanence and intention in seemingly fixed relations. In extension of the book’s larger project of deconstructing boundaries between discrete, categorical objects, as well as troubling the boundaries between the internal and external, “Housekeeping” depicts violence, pressure, and force in the connections of hinges, stitches, and bindings. In contrast, this section is also preoccupied with “mess[es]” and “spill[ing],” with imagery of water and its fluidity. Similarly, the section takes special interest in sound, and especially immaterial light. Tension marks the poems in this section, but the cause of such tension remains largely abstract until we read in the section’s final poem—“Standing on the Lawn Outside Your House with a Match and a Gallon of Gasoline”—of “the first fist you seamed / into my cheekbone was to get to the proof, / to the pit of the marriage.” Confronted with explicit violence, we find in the last lines of the poem a speaker transcending the categorical question of “what kind of woman” to instead assert herself in unequivocal being—“I am.” Left on the precipice of her action, we can trust that the speaker has found herself: “I still don’t know what kind of woman / I am. But the flame nears the fingers / that trust the match, as close as the skin / can stand it to singe, I call this the nerve / to find out—.”

Toliver’s second and longest section, “Ideal Machine,” fragments language further than “Housekeeping.” Two columns of fragmented phrases descend down the pages of this section like falling ash and sparks. Symmetrical images of medical scans, a moth, and an ink blot intersperse these floating phrases, which intertwine but never quite cohere. The poems of “Ideal Machine” draw connections between the birth of a child and the excision of a tumor – both generated by the speaker’s own body – but are more broadly interested in slippages between all sorts of “matter.” The experience of this section mimics the vaguely hallucinatory experience of going under in surgery, where “everything is turning / into everything else.” Yet the experience is far from fearful, but rather full of wonder and awe. The epistolary form introduced in “Housekeeping” proliferates in this section, which frequently speaks to a “you” that slips between the speaker’s daughter, a tumor, doctors, a butterfly, the reader, and other ambiguous addressees. The speaker often articulates a relation of attachment to the “you” through the language of love or possession: “this mine,” “my sea glass my meteor.” This section is perhaps the most inviting of the book, as its sheer beauty combined with intense fragmentation permits readers to stop pressuring the language to produce coherent meaning. The section invites us instead to simply experience Toliver’s language like starbursts, or as an “unravel[ing].”

Toliver’s short third section, “Spectra,” is perhaps her most urgent and stunning. In these final pages we find ourselves at the end of the world, and perhaps the end of ourselves. “Spectra” imagines an un-alienated world or “second earth” – “it is dusk” – as it begins to describe “what survives” or what it might mean “to outrun the cantering dark.” Reversing the final image of “Kinesis,” here a child leaves the sea and “throws the light / back at the sky” in a move that might be read as an act of reciprocity with nature or perhaps a refusal of visual determinacy. While it problematizes categorization, Spectra retains an interest in the beauty of contrast in “cerulean singing against the clean / white buds.” This section seems to posit a world in which difference does not mean hierarchical categorization. Echoing her move from “kind of woman” in the final section of “Housekeeping,” Toliver here again replaces the question of what kind of thing with “the next kind thing.”

In the vein of Afrofuturism, “Spectra” gestures toward an alternative, emergent world “beyond dimension.” This world demands new affective relationships—an abundance of awe, an attention to magic—and a new mode of perception that recognizes the “certain aliveness” of other forms—tulips, apples, larvae. In this world creation is born of the saturation of self with world and world with self in dynamic relation: we are all “absorbed and absorbing the universe,” and “the totality will catch you / the totality will let you go—.” In its interest in totality, “Spectra” is particularly attentive to the ways in which totality or unity is not apparent, but rather a goal or a shift in perspective that requires a concerted attention, a responsibility: “there is a vigilance to it the desire / to include everything.”

“Spectra” leaves its readers with hope in the human capacity for change in its assurance that:

there is a way to the light if we want it:[…]Beyond the buoysBeyond the bridge litInside the mindOut of the only country we knowout where the darkness is a mirror seenthrough tothe place beyonddimensionbeyond the last blue rift in possibilitywhere everything splits and shimmersbeyond what brought us hereand what will take us back.

“Spectra” decenters without abandoning the human by reminding us that the world goes on without us, beyond our perception. The poem also asks us to recognize our perception as deeply relational: “I see / myself through you.” Instead of thinking the future as inevitable or predetermined, “Spectra” insists on human—and merely human—agency in “the wide-open field of the now,” where it is not too late and still “we can make an eden / out of even this.” Spectra as a whole ultimately offers a stunning expression of alternate modes of being and perceiving a world “beyond,” if only we would see it, want it, and make it.

Katherine Preston is an English PhD student at Brown University. She holds a B.A. in English and Political Science from Williams College. She specializes in poetry and poetics.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig