by Alexander Ullman

Published by University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012 | 322 pages

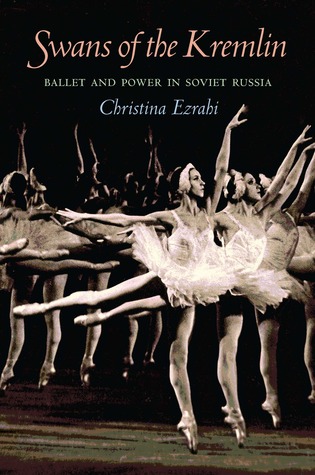

Ballet held a curious place in the Soviet imagination. As the cultural jewel of the tsarist crown, it was associated with both imperial power and the decadence of the elite. Accordingly, in the tumult immediately after the October Revolution in 1917, it was uncertain what role it might play in the new society, and for a time it seemed as if the whole apparatus of Russian ballet – expensive, elaborate and artificial – would be swept away. Yet not only did it maintain a foothold in post-Revolution cultural life, it actually rose in esteem and political favour, becoming one of the USSR’s most prized assets. In Swans of the Kremlin, independent scholar Christina Ezrahi tells the story of the two most famous Russian ballet institutions: the Kirov, in Leningrad (now known again by its pre-Soviet name, the Mariinsky); and the Bolshoi, in Moscow. Her narrative takes us from the turbulent aftermath of the Revolution to the Brezhnev era, and provides a fascinating glimpse into some under-explored archives. Though ultimately the evidence Ezrahi presents does not quite support her central thesis, the facts under discussion make for a compelling story nonetheless.

In her first chapter Ezrahi paints a convincing picture of the confusion and uncertainty of the post-Revolution years 1917–22, when the theatres struggled to stay afloat. Fuel shortages, extreme cold and malnourished dancers were all serious problems, but a more fundamental threat was the ever-present possibility of closure. Various politicians and prominent cultural figures argued over whether ballet could be rehabilitated as a proletarian art form, or whether it was simply a “museum art”, a “hothouse plant” that should rightly be extirpated from the national culture. How, they demanded, could the stylised, aristocratic language of classical ballet possibly hope to express the concerns of the Soviet people? Ezrahi is right to observe that in many ways this was not a new debate – sceptical writers across Europe had been pointing out the inherent artificiality of ballet since its inception. Still, the debate took on a new urgency in the early Soviet era. Many commentators lauded pantomime or other (it was argued) more naturalistic forms of dance above classical techniques, declaring these to be more “Soviet” and appropriate. However, when free tickets to traditional ballets were made available to workers during this period, their opinion was made clear as they attended en masse.

As the Cold War deepened, culture became a crucial battleground. Russian ballet had an almost legendary reputation in the West, and the Soviet political regime realised that it could be a powerful tool of propaganda both at home and abroad. Ballet was, like all forms of art in the Soviet Union, closely monitored and controlled precisely because it was considered to be significant – those in charge of cultural policy believed that art could mould better socialists (could ‘engineer the human soul’, to use an oft-repeated Soviet political slogan), but also that it could demonstrate the superiority of the USSR. This dual demand, however – that it should compete on the world stage, but also be proletarian – posed a significant dilemma for ballet. The dancers faced endless edicts, comments and committee meetings; every decision was a protracted negotiation, and every aspect of their work – from the ballets they staged to the tights they wore – was scrutinised. Ezrahi is painstaking in her documentation of these discussions, dissecting them in intriguing detail.

Ezrahi is less successful, however, in substantiating her central thesis: that, despite persistent state intervention and frequent attacks in the press, the artists of the Bolshoi and the Kirov found ways to resist the state and assert their creative independence. This is a familiar revisionist narrative, and one that often appears in scholarly discussions of significant Soviet artists (Dmitri Shostakovich is a prime example). Ezrahi attempts to demonstrate that “artistic talent and imagination proved stronger than ideological constraints,” and that artists played the unwieldy bureaucratic system to their advantage. In her attempt to demonstrate this claim, however, she is forced to dilute the definition of ‘resistance’ to the point of meaninglessness. One of her main examples of such artistic defiance is Kirov ballerina Natalia Dudinskaya’s reluctance to stage La Bayadère, an ideologically suspect work that would probably have fallen foul of the authorities, during a Kirov visit to Moscow. Ezrahi sees this as ‘protecting’ the piece, writing that “loyalty was often simply nothing more than pragmatic accommodation to the system,” but – true as this may be – it is hard to see how one can interpret such accommodation as a form of resistance, any more than one can read the infighting and score-settling played out through various official meetings as gaming the system. In addition, as a result of her decision to arrange her narrative chronologically, it is made all the more obvious that instances of artists pushing the political boundaries generally coincided with periods where state control was temporarily relaxed. Visionary choreographers like Fedor Lopukhov and Leonid Iakobson met with success during the great flowering of the Soviet avant-garde in the 1920s, or later during the Khrushchev ‘thaw’, but were otherwise isolated and disenfranchised. The history of Soviet art is littered with such dead-ends, and Ezrahi fails to demonstrate that the ballet ever proved victorious over state censorship.

As a result of Ezrahi’s insistence on this thesis, and her accompanying focus on the inner workings of the Bolshoi and Kirov administrations, the work largely neglects the reception of ballet in the USSR more broadly. Though she initially implies that the “balletization” of Russia will be central to the book, she never really addresses how this transformation occurred. One of the most intriguing aspects of the first chapter is the way in which Ezrahi begins to explore the reception of ballet among ordinary people: after the collapse of the aristocracy, a new audience for the Bolshoi and the Mariinsky was abruptly transplanted in place of the old – an audience for whom ballet was initially entirely foreign, but with whom it gradually came to be genuinely popular. She begins the story of these strange bedfellows, but leaves it unfinished.

Despite these criticisms, Swans of the Kremlin is a compelling read. Ezrahi has been meticulous in her research, and has unearthed some fascinating stories. Her account of the Bolshoi’s performances in London in 1956 vividly conjures up the atmosphere of distrust, tension and excitement occasioned by their visit, and her anecdote about the hat-stealing Soviet athlete Nina Ponomareva is one of many amusing details that enliven the book. Though flawed, Swans of the Kremlin is an insightful and engaging document of an extraordinary era.

Originally from the UK, Caroline Waight has studied at Cambridge, Oxford and Cornell Universities. Her work focuses on music in the early twentieth century.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig