by Simon Demetriou

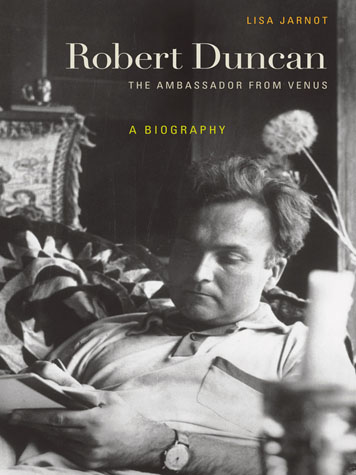

Published by University of California Press, 2012 | 560 pages

Robert Duncan had famous eyes. As a child he fell in the snow and his glasses shattered into his face and eyes, leaving him cross-eyed for the rest of his life. For him, this meant that he “had the double reminder always, the vertical and horizontal displacements in vision that later became separated, specialized into a near and a far sight. One image to the right and above the other.” Duncan’s poetry, too, is marked by this double reminder, though here one witnesses his mind’s sight, its displacement of entire worlds.

“The white peacock roosting / might have been Christ,” writes Duncan in the poem "What I Saw," from his 1968 book of poetry Bending the Bow. The single-sentence poem continues, pushing further back in time towards the common origin of the mythologies of Christ and Osiris:

The beginning of the poem overlays images: peacock, Christ, Osiris. How to understand this stratum? The last three lines: "the slit of an eye opening in / time / vertical to the horizon." Duncan physiologically saw things differently through his crossed eyes, but his upbringing and interests also attuned him to other, spiritual ways of seeing. The slit of the poet’s eye opens in time, but is vertical rather than horizontal. Duncan’s poetry attends not only to horizontal material—the Cartesian x-axis that plots time – but also the vertical, spiritual space – the y-axis reaching upwards and down, perpendicular to time – the space that has always been and always will be. Lisa Jarnot’s new, massive biography, Robert Duncan: The Ambassador from Venus, yokes together both poles, demonstrating how the full diversity of Duncan’s mythic creations—his poems and, indeed, his self—complement, but also partially misconstrue, the material life Duncan inherited and lived.featherd robe of Osiris,the radiant bird, a swosh-flash,percht in the treeand the other, the fumed-glass slidewere like night and day,the slit of an eye opening intimevertical to the horizon

It was easy for Duncan to mythologize his early life. He was adopted by two practicing theosophists, Edwin and Minnehaha Symmes. The Symmes, students of esoteric philosophy, chose Duncan on the basis of his astrological signs, which they read as suggesting he had worked in a past life as an inventor on Atlantis. Many of Duncan’s early memories involve being denied access into the rooms where his parents’ hermetic rituals were taking place. Still, he listened carefully and overheard them speaking about “things close to dreaming—spirit communications, reincarnation memories, clairvoyant journeys into a realm of astral phantasy where all times and places were seen in a new light, of Plato’s illustrations of the nature of the soul’s life, of most real Osiris and Isis, of the lost Atlantis and Lemuria, and of the god or teacher [his] parents had taken as theirs, the Hermetic Christos.” Based on popular occult groups like Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society of New York and India, the Symmes’ hermeticism created a home atmosphere that was erudite, inquisitive, and discursive—perfect for an aspiring poet. By four or five, Duncan was already monologuing to anyone who would listen, a practice that would continue his entire life. Consistently, the first thing mentioned during interviews about Duncan with friends and family, is the persistence of this voice over the years: “Attempts to keep up with his thoughts left me exhausted and sometimes dazed.”

Duncan was lucky to have a high school teacher—Edna Keough—who introduced him to the modernists, especially H.D.—an author he would spend most of his life writing a book about. Edited and reprinted recently as part of the University of California’s new multi-volume Collected Works, Duncan’s unfinished The H.D. Book, a book that served as the summa of his own theory of poetics, details his engagement with self-mythology, while rigorously engaging with H.D.’s work and the gnostic history that it, and his parents, celebrated.

During his undergrad years at U.C. Berkeley, two fellow students—Lillian Fabilli and Cecily Kramer—helped Duncan realize his latent poetic urges. At that time, in the late 30s, all male students were required to take part in ROTC drills but, one day, as Duncan describes in The H.D. Book:

I turned for the first time to read Joyce’s poems, cutting the pages as I went, I read aloud to two young girls—young women—whose sense of the world was deeper than mine, I felt, so that I was supported by their listening…”All day all night, I hear them flowing / To and fro,” I read aloud and paused before turning to the next poem. From the Campanile bells sounded…Turning from the book with dismay, I cried, “There is the bell, I have to go.” “You don’t have to go,” Lili commanded, raising her hand in a dramatic gesture that had been delegated its powers by the conspiracy of our company. “Stay with Joyce.” What we had been enacting, the reader and the listeners—the Muses, perhaps, for some serious amusement or enchantment had been worked out through our cooperation—celebrating this most high reading of the poem, was to become real. “Rejoice with Joyce,” Athalie commanded. A poem was to take over.Duncan soon dropped out of the ROTC and Berkeley to drift around, first to Philadelphia, and then to New York, where he fell in with Anais Nin and other artists. He moved frequently between different apartments and artist retreats on farms in upstate New York. Though it would take him another 20 years to publish his first major work, The Opening of the Field, Duncan was on his way.

It was during this period that he published The Homosexual in Society. A pioneering essay in its earnest, honest engagement with gay life in America, it is, in hindsight, both deeply moving and also quite problematic. In it, Duncan lambasts those homosexuals who cultivate a “secret language, the camp, a tone and a vocabulary that are loaded with contempt for the uninitiated.” He instead endorses a homosexuality that speaks not only to those “in the club” but to all mankind. Jarnot reads this as a transference of Duncan’s frustration with the exclusivity of the cultural avant-garde, and in this essay we see the beginning of the anarchist ideals that Duncan would espouse for the rest of his life, most famously in a late argument with the poet Denise Levertov over the proper reaction to the Vietnam War (Levertov preferring the agitprop, Duncan arguing for a deeply pained, mythological response). Regardless of its politics, the essay makes clear that Duncan was coming to terms with his new found life as double outsider—the poet and homosexual.

In 1946, Duncan moved back to San Francisco and befriended the poets Jack Spicer and Robin Blaser. These years are now known as the Berkeley Renaissance, coming a decade earlier than the more famous San Francisco Renaissance of the beat writers (both Spicer and Duncan were, famously, out of town when HOWL was first read). Sprightly in their bookishness, the three poets organized lectures, readings, and cooperative-writing evenings. It was a happy time—visiting poets and scholars lectured on Williams, Yeats, and Lorca, as a small community of mostly graduate student “disciples” assembled around Duncan.

During this period Spicer and Duncan developed one of the most important forms of post-modern verse: the serial poem, “a form similar to that of a comic book, where each poem overlap[s] narratively to maintain continuity between episodes of writing.” Though the form resembles, in its seriality, the more familiar sonnet sequence, the serial poem specifically reacts against the coherent reasoning of the sonnet sequence, as well as the totality of the epic form. Joseph Conte, in his fantastic essay "Seriality and the Contemporary Long Poem," notes how:

The serial form in contemporary poetry…represents a radical alternative to the epic model…The epic is capable of creating a world through the gravitational attraction that melds diverse materials into a unified whole. But the series describes an expanding and heterodox universe whose centrifugal force encourages dispersal. The epic goal has always been encompassment, summation; but the series is an ongoing process of accumulation. In contrast to the epic demand for completion, the series remains essentially and deliberately incomplete.Spicer is, perhaps, most well known for his use of the form—his After Lorca is a series of letters to, mis-translations of, and lyrics on Lorca—but Duncan would also employ the form in his later series The Structure of Rime and Passages.

Spicer and Blaser were important confidants and friends for Duncan—but in 1947 Duncan encountered a personality of a different magnitude entirely: Charles Olson, one of the dominant personalities of the Black Mountain School. If Duncan is famous for inventing an outsized version of himself, Olson simply was outsized—6’8,” powerfully loud, unceasingly energetic, almost singularly charismatic. Even in the company of luminaries including Buckminster Fuller, John Cage, Willem de Kooning, Max Dehn, Walter Gropius, etc. the force of Olson’s personality and intellect remains the stuff of legend. Olson was a Melville scholar who, though he had worked for the Democratic National Committee in his early years, grew increasingly disgusted with politics and instead threw his entire being into poetry. His manifesto, “Projective Verse,” and his epic The Maximus Poems, were to his contemporaries what Pound’s A Few Don'ts by an Imagiste and Cantos were to the preceding generation.

Duncan was taken up by Olson’s “open-field poetics.” Open-field poetics, or “composition by field” is a radically improvisational poetic method that, rather than beginning with form—say, a sonnet or rondel—and applying content—say, on love or death—begins instead with content from which, subsequently, form radiates. Or, in Olson’s more hyberbolic words: “FORM IS NEVER MORE THAN AN EXTENSION OF CONTENT.” In Olson’s poetics, as the content of open-field poem is never fixed, the poem’s form must also perpetually change in response. He writes: “ONE PERCEPTION MUST IMMEDIATELY AND DIRECTLY LEAD TO A FURTHER PERCEPTION… get on with it, keep moving, keep in, speed, the nerves, their speed, the perceptions, theirs, the acts, the split second acts, the whole business, keep it moving as fast as you can, citizen. And if you also set up as a poet, USE USE USE the process at all points, in any given poem always, always one perception must must must MOVE, INSTANTER, ON ANOTHER!” Olson thus introduced into poetry a formal equivalent to Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity.

Duncan met other poets associated with Black Mountain, as well—most importantly, for his own development, Robert Creeley and Denise Levertov. He corresponded with both throughout his life, though, as noted above, sometimes, begrudgingly. Still, his early letters to Levertov show how important both were to him, clarifying his own version of open-field poetics.

While most of his peers embraced strongly political (or auto-biographical) poetics, Duncan instead, as with Olson, developed a more chaotic approach, in which the material and the spiritual worlds entwined. Unlike Olson’s work, which churns with the history of Gloucester, MA, for Duncan the world is only partly material; the spiritual world is always immanently present. How Duncan understood this material/spiritual world is difficult to say. Certainly his ideas were influenced by his parents’ theosophy. Reading Duncan can be a challenge for the contemporary reader versed in the arguments of the New Atheism. In his poems one encounters the suggestion that there exists something beyond what we are able to perceive. The Opening of the Field begins with one of Duncan’s most famous and most anthologized poems, Often I am Permitted to Return to a Meadow. Its title is its first line, and the poem continues:

as if it were a scene made-up by the mind, that is not mine, but is a made place, that is mine, it is so near to the heart, an eternal pasture folded in all thought so that there is a hall therein that is a made place, created by light wherefrom the shadows that are forms fall.This made place, this eternal pasture that comes, not just from the poet but from the world, and yet is beyond the world, this is not new to modernist poetics—there are intimations of this in Yeats, Pound, and H.D., to name a few. Still, Duncan is among the most continually, and deeply, engaged of poets in his role as spiritual witness.

Read next to Duncan’s own writing, Jarnot’s biography acts, in its portrayal of the historical life, to rein in Duncan’s embellishments, to present a demythologized and quotidian portrait. Hers is a thorough and three-dimensional view of the man in all his complexity and at times, all too familiar blandness. While it is helpful, even crucial, to capture Duncan in this light and to present him as a working poet and craftsman rather than as a siphon for the godhead, it is also, at times, frustrating how close Jarnot holds her readings of his poems to the archival record. Her astute autobiographical criticism is, of course, good to have, and the book is a wonder of patient historical archeology. But with Duncan, who always, in his own telling, had one eye on the material world and the other on the spiritual, one wishes for a more open reading of the poetry. Still, there remains something marvelous in Jarnot’s showing that Duncan’s made place, his entirely extraordinary mythology, was the product of the most ordinary of men.

Devin King is a writer, musician, and teacher working in Chicago, IL. His long poem, “CLOPS,” is out from the Green Lantern Press, Chicago, where he is now the poetry editor. A new chapbook, The Resonant Space, is out from The Holon Press, Chicago. Both are available here. General info available here, and previous MAKE reviews available here, here, and here.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig