by Killian Quigley

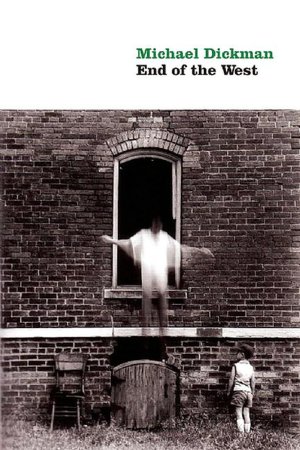

Published by Copper Canyon Press, 2009 | 96 pages

It’s tempting to talk about Michael Dickman’s life.

For starters, he seems to be writing about it—and the details are so dementedly disturbing, and his tone so disturbingly straightforward, that even the most courteous reader can’t help rubbernecking, and even the most hardened can’t help hoping that these are persona poems. If his poems beg to be fact-checked, in other words, it’s not because Dickman doesn’t seem trustworthy. It’s because he does:

And then there’s the twin thing. No, make that the young, handsome twin thing. No, wait—the young, handsome, successful poet twin thing. From their first New Yorker publications (four months apart) to their Fine Arts Work Center fellowships (one year apart), to their matchy-matchy MFAs (from the Michener Center for Writers at UT Austin, both class of ‘05), Michael and his twin brother Matthew have hit nearly every jackpot in the casino of poetic accomplishments—twice. Again, one wonders: who are these guys?I didn’t shoot heroin in the eighth grade because I was afraid of needles andstill amMy friends couldn’tnot do it—Black tara leather beltand sunlightScary parentsThe filled holesall afternoonthen we went to the movies(“Scary Parents,” p. 6)

So much for resisting temptation. In a way, though, there’s something heartening about the irresistibility of the Dickman’s biography, insofar as it suggests that poets can still achieve some level of celebrity. It’s to their credit as people that the Dickmans avoid using “the twin shtick” to market their work, and to their credit as poets that they really don’t need to anyway. These guys may be twins, but more importantly—they’re good.

The End of the West, Michael Dickman’s first book, is a spare, elliptical exploration of loss, violence, betrayal, and other inevitable disappointments suffered at the hands of friends, family, and God. If this sounds like a bummer, well, it is and it isn’t.

In Dickman’s world, the bummers and not-bummers tend to blur and overlap, as do other dichotomous pairs—life and death, for example, or violence and tenderness, poetry and profanity, universal and specific. The address in these poems is similarly blurred, as though the poet, talking to himself, hears someone else answer—or, expecting an answer, hears only an echo. Indeed, the self itself is dynamic, chameleon, duplicitous:

Or maybe more than one. Dickman’s verse is characterized by schizophrenic line lengths, associative leaps, slippery pronouns, and unattributed speech; he often seems to be having both sides of an argument. There’s something haunting about this technique, especially in a collection so saturated with loss. Not only does Dickman contain multitudes, he’s also surrounded by ghosts:There are monstershidingall over the neighborhoodMaybe you are one(“Little Prayer,” p. 28)

His dead friends do come back a dozen or so pages later, in a poem called “My Dead Friends Come Back.” And they’re not the only ones. Themes and images vanish and resurface throughout this collection. Shaved heads keep showing up, for example, as do churches, snow, “that first time, on her living room floor,” waiters, various fires, etc. As a result, The End of the West feels like a kind of elegiac riddle, each recurring image a clue to be gathered, the collection itself circling some central, mysterious truth that always hovers just out of reach. Or one might say Dickman’s telling that truth, but telling it slant. After all, success in circuit lies…Listendon’t let any of my dead friends come backThere they areWalking up the streetdragged up the streetby their hair…(“Little Prayer,” p. 29)

Perhaps one of Dickman’s dreaded/revered “dead friends” is in fact Emily Dickinson, back from the grave to reclaim this technique. (And also her em-dashes.) Often, though, Dickman’s friendship with Dickinson (and the circuitous lyric tradition she represents) seems more conflicted. It’s one of those arguments he’s having with himself, epitomized by the opening of “Late Meditation:”

But in the very next line, Dickman plays his own Devil’s Advocate:What are you going to do?Describe the lightfallingthrough the pitch pinesagain

Tell the truth straight, Dickman seems to insist, as he yanks his gaze from beauty to violence and back again, playing tug-of-war with his own lyric impulse. Perhaps another of his dead friends, Wallace Stevens, is the drill sergeant here, Dickman squinting at the snow man and repeating through gritted teeth: “One must have a mind of winter, one must have a mind of winter…”Yesterday we put all our kids in the car, doused it with gasoline, and lit it on fire.(p. 34)

Elsewhere, Dickman uses a gentler touch. In “Returning to Church,” he soothes: “Do you want to be home forever? / It’s all right if you do” (p. 25) Later in the poem, he’s defensive but defiant: “I don’t have to explain… // I don’t have to be embarrassed” (p. 26) Here, Dickman seems to be positioning himself against those salient contemporary lyric trends: obfuscation and irony. “Returning to Church,” in case you missed it, is a poem about church—so where’s the knowing wink? The playfulness? The complex allusion? The secret critique of belief? Could his tone…could it possibly be…earnest?

That earnestness is so often portrayed as a risk here is a function not only of the ironic zeitgeist that is contemporary poetry, but also of Dickman’s overarching worldview within The End of the West. When everything is blurry and equivalent, it’s risky to care, to hope for one thing over another. We should know by now that the tender outstretched hand will suddenly, inevitably clench into a fist. This is a world where a mother “[leaves] hypodermics / between the couch cushions / for us to sit on,” (“Scary Parents,” p.8 ) where a father:

Still, Dickman has his moments of optimism, and they come at predictably unpredictable moments. Smack in the middle of “Scary Parents,” for example:Stumbling into the bedroom at three in the morning the two of us asleepand all that moonlightand beat his son’shead againstthe headboard

You fucker you fucker you asked for it

The moonHis jaw splashed across the pillowcase(“Some of the Men,” p. 11)

Yes, that’s the same poem mentioned above—the one with the hypodermics in it. Again, the blurring goes both ways; behind each carrot is a stick, but behind each carful of flammable children there’s also the lovely light. Friends may die, but they also come back. Every so often, in the midst of all the horror, Dickman lulls us into thinking that maybe it’s okay, just this once, to hope.Stillthere is a lot to pray toon earth(p. 7)

Then again, maybe not. Variations on the phrase “asked for it” come up on multiple occasions in The End of the West, as though hopefulness is not only futile and risky, but actually incites punishment. The most notable example can be found in the final, jarring lines of the collection, when we get close enough to hear what those dead friends are actually saying:

And that’s it: the end of The End of the West. There is no neat bow, no cute wink, no lyric description of the light, to bid us adieu. It’s a startling, effective move, at once deeply unsettling and mischievously satisfying. If we readers had our hopes up for some respite, for the tidy optimistic lyric ending—well, we learned our lesson. What’s more, we had this shit coming. We probably even asked for it.You had this shit coming, they whisperfrom the cornerYou’re going to be sorry(“The End of the West,” p. 88)

Ali Shapiro is an MFA candidate a the University of Michigan. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in RATTLE, Redivider, and Linebreak, among others. She’s won various awards for her writing and other exploits, including two Dorothy Sargeant Rosenberg Poetry Prizes and a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig