by by Margaret Kolb

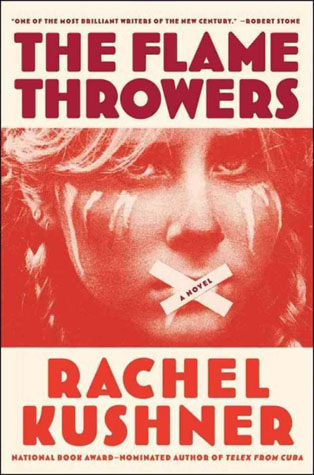

Published by Scribner, 2012 | 400 pages

Early in The Flamethrowers, our protagonist, Reno, witnesses a strange and startling scene. While motorcycling cross country, she stops for gas and overhears a couple half arguing, half flirting at the pump next to her. The man removes the nozzle from the gas pump and “jerk[s] it at the woman,” sloshing gasoline “on her bare legs.” He then pulls a book of matches from his pocket, lights one after another, and flicks them at her, “little sparks—threats, or promises—that died out limply.” The woman makes a meager protest, dries herself with a paper towel, and finally “smile[s] at him like they were about to rob a bank together.” This playful yet sinister exchange serves as a kind of synecdoche for Kushner’s work as a whole; The Flamethrowers is a novel that courts violence, keeping its reader tense, alert, and braced for impact. Or immolation.

Both unassailably cool and intellectually satisfying, Kushner’s second novel—after 2008’s Telex from Cuba—is about the trifecta of power, sex, and speed that drives modernity, as well as those forces that impede it. It explores these themes largely through Reno, “a Nevada girl and a motorcycle rider” who moves to New York City in the mid-seventies to become an artist. There, she meets the accomplished—and much older—minimalist sculptor, Sandro Valera; his best friend, Ronnie Fontaine; and other members of the city’s thriving art scene. Kushner’s “innocent and ambitious” protagonist quickly falls for Sandro, an Italian émigré and reluctant heir to the tire and motorcycle company his father founded after WWI. While the novel is mostly concerned with their relationship, it also examines notions of time, history, tradition, and upheaval. The Flamethrowers opens with Sandro’s father, T.P. Valera, as he narrowly escapes from a skirmish with German soldiers while serving in Italy’s cycle battalion in 1917. Kushner continues to cross cut between his story and Reno’s, priming readers for the many collisions between these seemingly disparate worlds that follow. As her narrative leaps from pre- and postwar Italy to Amazonian rubber harvesters to underground militant groups in the U.S. and abroad, Kushner demonstrates the ways in which history is yoked to the individual, and not the reverse. This is the very spirit of revolution, which animates each of the worlds she depicts.

Despite the fact that T.P. Valera comes of age in fascist Italy and Reno inhabits New York’s East Village in the 70s, the two have much in common. They are both drawn to speed culture and the machines that enable it, sensing in these things something “virile, metalized,” that sates their shared “need for risk.” However, while Valera channels the zeal of the Italian Futurists—whom he briefly joins—into engineering and industry, making his indelible, and, fundamentally, neocolonial mark on the world, Reno is interested in speed’s capacity for erasure. Her fascination with “[d]rawing in a fast and almost traceless way”—with the “trace of a trace”—suggests a desire to achieve something like “escape velocity” (in physics, the speed at which an object forever breaks free of another massive body’s gravitational pull). This concept subtends her artwork, her day job, and, in many ways, her gender—something with which Kushner’s text is deeply engaged.

As the novel progresses, a dynamic emerges among Reno, Sandro, and Ronnie that will be familiar to some readers. In her classic texts, Between Men and Epistemology of the Closet, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick argues that women often mediate the repressed, homosocial attraction two men feel for one another. Consequently, women are reduced to little more than convenient go-betweens—blank screens onto which male-male desire projects itself. In The Flamethrowers, Sandro literally instructs Reno to “be a conduit.” However, Kushner revises Sedgwick’s paradigm in a significant way. In positioning the female conduit center stage, she renders Reno’s experience of this role in its full complexity and thus, perhaps, at least partially redeems her.

Ultimately, Kushner’s portrait is too intelligent to reduce to any simple, dogmatic reading. Although Reno offers many astute observations regarding gender, she seems torn between wanting to subvert them and, well, not. “I wanted to be looked at. By men” she confesses even as she lights out for the territory, as it were, and breaks the 1975 land speed record on a Valera motorcycle: “I was, improbably, the fastest woman in the world, at 308.506 miles an hour.” In struggling to assert herself as an artist, a lover, a revolutionary, Reno oscillates between agency and passivity. Even in relation to the novel’s curiously elided climax—a kidnapping—Reno cannot escape the role of intermediary, of mere accomplice. Thus, while one might be inclined to read The Flamethrowers as a feminist text, much of what happens to Reno is instigated by men who understand (and manipulate) her better than she does herself. The power of this novel lies in its ability to resist any definite, unambiguous interpretation, political or otherwise. As one character observes, “What happens between bodies during an insurrection […] is more interesting than the insurrection itself.”

Toward the end of The Flamethrowers, Kushner’s tightly wound narrative begins to unravel, along with its central characters. The prose downshifts into a lower gear, allowing the reader to take things in—to assume a meditative, rather than reactionary, position. Although Kushner writes exquisitely throughout, the lyricism that characterizes these final chapters is simply stunning—the conclusion, both haunting and lovely.

Christine McCulloch received her PhD in English from Emory University in 2012. Her research examines representations of the techno-industrial accident modern American literature and film. Currently, she teaches English in Atlanta, GA.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig