by Killian Quigley

Published by Birds, LLC, 2010 | 72 pages

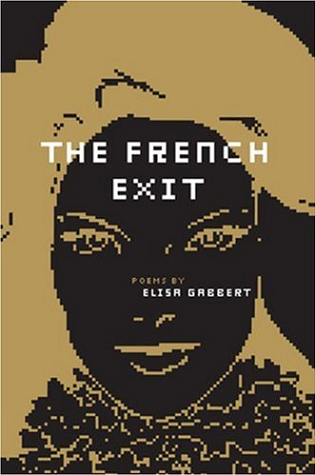

The cover of The French Exit, Elisa Gabbert’s first full-length collection of poems, depicts a woman’s face disintegrating into pixels. The text on the cover, too, is pixellated—the “X” in “Exit” a criss-crossed matrix of squares, all the B’s and S’s angular, digitized, like on an old Texas Instruments calculator screen. The overall effect is at once archaic and au courant, and as such there’s something disjunctive about it—technology (the zoom-in, the ultra-close-up) revelling in its own pixellated deficiency.

Of course, you can’t judge a book by its cover—or by its title, which, in case you were wondering, means “to leave without saying goodbye.” In the case of The French Exit, though, both title and cover offer useful angles at which to approach the collection. Like the title, many of these poems employ a sly brand of humor to temper the painfulness of goodbyes, though Gabbert’s cleverness and wit belie the seriousness of her project; at its heart, this collection is a relentless examination of exits and all that comes after them—memory, nostalgia, longing, questioning, regret. But close examinations of such hazy realms prove necessarily difficult for this poet, and so like the cover-woman’s face, many of Gabbert’s poems have a certain pixellated quality—she zooms in so close that things lose their meanings. Language, for example:

Here, form fits content: Gabbert’s shifting italics allow a reader to experience, rather than simply understand, the fickleness of language and “meaning.” Writers before her have tried similar tricks, but few are as playfully accessible; reading Gabbert is nothing like reading, say, Gertrude Stein. Still, a familiar thread of semantic uncertainty runs through The French Exit, as when a poem ends:It doesn’t mean anything.It doesn’t mean anything.It doesn’t mean anything.It doesn’t mean anything.(“Poem With Negation,” p. 64)

Or when images refuse to be pinned down:…The mica sparklesthrough him/her/it.(“Near-Life Experience, p. 51)

Or when even the physical world and the physical body’s responses to it no longer hold their shape:…One is like dust.Cricket legs/wings. Another: approachingthe treeline to find they’re not faraway, just very small trees.(“Poem With Intrinsic Music, p. 22)

Again, it’s not just the images or themes that prove slippery in these poems, not just the description of the treeline confusion or the simile of the car—it’s the words themselves, “pain” in quotation marks, nouns backslashed and inexact; it’s the sense that not only memory, but language itself is unstable. The words used to describe a memory begin to seem like the pixels on the cover. The remembered world is a constructed thing, Gabbert suggests, a series of words we assemble and reassemble to try and conjure the people, places, and things we have lost. Zoom in too close, and the seams start to show. Pull too far back, and the whole thing seems like a dream.You kick a car, and it crumples apartlike a death-hollowed tree.“Pain” ripples out in a wave.(“Commissioned,” p. 9)

Dreaming and memory tend to blur in The French Exit, and the details of the dreams and memories Gabbert depicts are often further blurred. One obvious culprit here is the human mind, its weakness exposed by Gabbert in “Poem With A Snowman” (p. 63): “Think nothing / and you’re still not thinking nothing.” As in “Poem With Negation,” the playful italics in this Stevens homage call both perception and the language of perception into question. But a second clear culprit is time, which in the world of The French Exit proves even more fickle than language. In “Decoherence,” she describes a “sex-dream-cum-anxiety dream” (even her dream-types are blurred!) involving a former lover:

Indeed, there’s something “quantum” going on in many of Gabbert’s poems, and as in “Decoherence,” these moments often coincide with gestures towards film:my ex decides at the last minutehe’s not interested in giving me another chance—my current bedroom, where he’s never been.The light black & blue like night on film.A dream of the future, blurring the past……He was doing this quantum thingeverytime I looked away—half in the bed and half leaving.

Film is one way of recording the past, and so Gabbert’s interest in it follows with her inquiries into the construction of memory. But film is hardly the only recording medium in contemporary culture, and The French Exit – the central section of which is comprised entirely of “Blogpoems” – is firmly rooted in the contemporary. If Gabbert’s inclusion of Internet vocabulary were purely for its own sake, the idea of these “Blogpoems” – of which Gabbert wrote one-a-day as part of a project for a friend’s blog – might seem precious or overly clever, fluffy as Flarf. But in the context of The French Exit, the blogging urge—to record, to tell, to preserve—takes on larger significance, as does technology itself.It goes backwards, starting in the oubliette—the end of my life as we know it—and then I’m tumbling up the rabbit hole.Hair billowing out like I’m underwater.The Seven Sisters in the distanceThe Well-Tempered Clavier in reverse.The man who pushes me pulls me up,embraces me. We enter a roomby way of an exit. It’s an inquiryinto causation…”(“Must-See Movie,” p. 19)

Technology makes cameos outside the blogpoems, too, as in “Screenshot For Allen” (p. 61), which begins:

There’s a certain earnestness here, too, a sense that technology, despite its apparent capacity to record and preserve and connect us, is not exactly a cure-all for distance or the passage of time. The speaker in this tender, longing poem is reduced to just a speck on a screen. Which would seem to be better than nothing, but is it? “My emotions are all set to default,” Gabbert writes in another poem (“Poem With A Plot, p. 58), and the computer-speak is no accident; if the self is just a speck, if every single tiny thing is recorded and preserved, if we can, in a sense, “skip back to [our] fave / scenes”—what then do we make of memory, not the “storage” of our hard drives but the kind in our hearts and heads, the kind which still blurs and shifts and refuses to mitigate the inevitability of loss?Here’s you. Here’s your street. Now zoom out—way out.That speck on the right-hand side by the scroll bar is me.

Gabbert senses danger here; technology in The French Exit is a force both powerfully appealing and powerfully alienating. She wonders: “How does my x-ray vision / know when to stop” (“Poem With A Superpower,” p. 26)? Or, faced with a world that often seems abstracted, surreal, she asks: “Where is the war? I can’t see it” (“Walks Are Useless II,” p. 54). But there are limits to technology’s power, as Gabbert articulates sidelong:

Gabbert’s use of weather as the “for instance” in this poem might seem a non-sequiteur, as its literal connection to “our desires” is a bit oblique. But it’s the leap, the sense that the speaker is grasping at straws, that so poignantly renders the simultaneous helplessness and awe the speaker feels in the face of the “problems” of the world. For all their heady questioning, Gabbert’s poems are still deeply touching, saturated with a sense of longing not only for the past, but for a present reality that is tangible, meaningful, real. “The problem of weather” might as well be the problem of memory, or time, or something else equally overwhelming and unsolvable. In the face of such problems, The French Exit is torn: on the one hand, wanting to believe that technology (or, for that matter, the recording device of poetry) can solve them; on the other, to believe that they’re too personal, unique and meaningful to be solved.…And yetas far as we’ve come, technology still lags behindour desires. For instance science hasn’t solvedthe problem of weather: how much of it there is,and how it is literally everywhere.(“Blogpoems Are Ideas,” p. 39)

Gabbert does propose one solution:

But this is the same poet who believes “the whole point of a stab wound // is the poignant memory” (“Poem With Variation On A Line From Saturday Night Fever,” p. 25) — grim, perhaps, but also reverent, fierce. Though Gabbert certainly wrestles with memory, the human heart at the center of The French Exit can’t help but believe it’s all worth it, even the stab wounds, even the scars—which, after all, are the details that make up this book.In the best of all possible worldsyou die instantly, beforethe formation of memory, scars.(“X”, p. 14)

And because Gabbert strikes such a perfect balance between heart and head, between cleverness and earnestness, between language that demonstrates its own fallibility and language that is surprisingly, perfectly precise—this book, too, amounts to a great deal. Contrary to the quick, clean getaway implied by its title, The French Exit is a kind of quantum goodbye, a gnomon of a book the very presence of which is defined by all the exits it keeps trying—and charmingly fails—to make. Gabbert’s observation of a roadkill squirrel could also be applied to her poems – particularly her last lines, which are so tightly crafted that we relish their completeness even as we ache for them to continue — and to The French Exit as a whole, in all its quantum bittersweetness:

…It wants to keeprunning forever, butit can’t stop stopping.(“Elegy at Chestnut and River,” p. 57)

Ali Shapiro is an MFA candidate a the University of Michigan. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in RATTLE, Redivider, and Linebreak, among others. She’s won various awards for her writing and other exploits, including a Dorothy Sargeant Rosenberg Poetry Prize and a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig