by Katherine Preston

Published by Yale University Press, 2017 | 288 pages

I admit it. I love Hugh Grant movies. While stuck inside this past week, it was Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994), where Grant plays Charles, a bachelor with no real worries in life except to survive the matrimony of others. He’s perpetually single and fine with it, until he meets the similarly charming Carrie (Andie MacDowell). “Charles keeps running into a fascinating American girl at various weddings—can they ever get together?” reads the Amazon description. The third wedding is Carrie’s to the stiff Hamish, and the fourth is Charles settling for old Lydia, so the answer seems to be “no.” But just as Charlie is about to say, “I do,” Carrie shows up single and divorced. After rejecting Lydia at the alter and surviving a simultaneous fist to the face, Charlie proposes to Carrie in the final scene, her “I do” an agreement for them never to be married. You’ll have to see it to find out about the funeral.

How is the plot anything but ridiculous? It turns on Charlie’s brother David (David Bower), who is deaf. He attends every wedding, where Charlie speaks to him in sign language. While Charlie just can’t tell Carrie how he feels, David is someone he can confide in privately, someone who knows the truth. That’s why when Charlie’s about to be married and the priest asks anyone who would object to the marriage to “speak now,” David publicly signs for Charlie to translate out loud that the he is in love with someone else. Though it is a truth voiced through the translation of his brother’s signing, Charlie thus speaks his truth for the first time. And then he gets the girl.

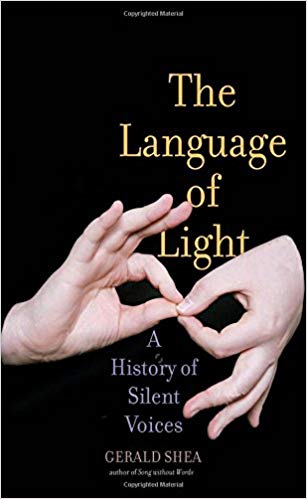

The film tickles all the spots that a romantic comedy should, but it also, I think, stirs up several important questions: how is disability, specifically deafness, related to social institutions? What sort of narrative structures does disability help stabilize? David is a character (and an actor) with a disability, but in some sense he is also a metaphor—a flat character that symbolically represents Charlie’s inability to fit the normative structures of marriage. The inability of Charlie to speak his truth is made an ability precisely because of David’s disability. The plot of the film, while it is really about a character’s struggle with the pressures of marriage, reproduces another form of normality: that of the able-bodied. As Gerald Shea’s The Language of Light shows us, these questions about normality, disability, social institutions, and representation are not merely the purview of romantic comedies (hardly!), but also the stuff of history.

Shea describes his book on the opening page as “intellectual history, an exploration of certain ideas about language,” and it is certainly that. But it also very much a history of pedagogy and deaf educational institutions. In 1785, Charles-Michel de l’Épée established St. Jacques, the first school for the Deaf in Paris, where he developed his own complicated “methodical” signs—signs he created by studying French grammar and etymology; l’Épée was succeeded by Auguste Bébian, who helped shift Deaf education at St. Jacques away from methodical to more natural signs, or signs that deaf students were already using; Laurent Clerc followed in Bébian’s footstep, bringing French Sign Language (LSF) to American shores in 1816 and established, along with Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, the first American institution for the deaf, and the first to use American Sign Language (ASL); and into the 20th century, William Stokoe, Chaucerian scholar turned linguist, broke ASL down into three essential components, what Shea helpfully calls “a specific motion,” where “a certain shape of the hands” is made “in a particular place on or near the body.”

There are certain limits to the content of Shea’s intellectual history. To any scholar of deaf studies, the stories will be familiar, and this narrative can often read as a cataloguing of historical figures. Also, because Shea restricts his analysis to the histories of France, England, and the United States, one is left wondering about the other ways in which sign language intersects with identity outside the history of white Europeans. This restriction does, however, have the benefit of shedding light on the ways in which the debate over how to educate the Deaf is also a debate about nationalism. As Shea reminds us, the history of deaf education begins not with any attempt to make the deaf better educated, but rather from the desire that they be able to “speak” normatively at all. For, as it turns out, “a central problem of aristocratic families in Europe was that Deaf offspring had to be able to speak in order to inherit.” So controlling deaf education became a way for the nation to control the bodies of a population that did not conform to able-bodied norms.

Shea’s most compelling narrative in this history of ideas is this one of educational control. In fact, it’s in this narrative that the “ideas” in a “history of ideas” takes on a double valence: the book is an history of changing ideas about deaf education, but Shea also shows how for much of history, hearing educators attempted to suppress the notion that Deaf peoples had any original ideas themselves or were even capable of independent thinking. His main narrative structure in this historiography is framed around a debate between those who favored sign language and those who favored “oralism,” or what he describes as the “unflagging belief in communication by speech and lipreading.” This latter philosophy, which had no basis in scientific fact or the personal experience of the Deaf, still became an insidious ideology for the suppression of the Deaf and the protection of hearing educators’ jobs.

This debate narrative gets heated, for it features family vendettas and workplace competition (as when Bébian is dismissed from his job after hitting a colleague—one who favored the oralist method—over the head with a set of keys). The Language of Light has its heroes who, though mostly hearing persons (l’Épée, Bébian, and Stokoe were not deaf), championed sign language as an effective pedagogical tool and an important mode of cultural expression for the Deaf. But it also has its villains: Alexander Graham Bell, for example, the famed inventor of the telephone, was a staunch eugenicist who viewed deafness as an illness and actively campaigned against the teaching of sign language. In a chapter entitled “Helen Keller: A False Symbol,” we learn that Anne Sullivan, Keller’s companion and teacher, worked to suppress any sort of independent communicative ability Keller had. The final villain of the book is not a person but a technology: cochlear implants. One can’t help but associate the success of this now billion-dollar industry that touts itself as a “solution” to the “problem” of deafness as an extension of the oralist ideology, where “the very faculty that Deaf children lacked should be the instrument”—in this case, the literal technology—“of their instruction.”

Shea follows a recent turn in Deaf scholarship, as Carol Padden and Tom Humphries pioneered in their Inside Deaf Culture (2005), toward combining scholarly research with personal experience. Though much of The Language of Light resembles Shea’s earlier memoir Songs Without Words (2013), the narrative here doesn’t revolve around Shea’s biography; a good thing, too, as Songs Without Words can at times read like a cringeworthy resume of white privilege and access. In The Language of Light, the personal details are more tactfully placed within the historical narrative. Shea, partially deaf since the age of six due to scarlet fever, at times introduces his personal experience with sign language and lip-reading into the history to refreshingly remind us that this history is often not told by the Deaf, and that this historical writing (like all good historiography) is situated.

Despite its Manicheism and at times overwrought style, especially in the portrayal of the war between the proponents of sign language and those of oralism, Shea’s book is a serious work of scholarship. And like Harlan Lane’s When the Mind Hears: A History of the Deaf (1984), it is simultaneously a history and a “study in the anatomy of prejudice.” Shea’s book avoids some of the pitfalls of Lane’s historiography (an entire first half of which reproduces the history of American Deaf culture by writing, awkwardly, in the first person from the perspective of Laurent Clerc), and it does this by striking a balance between rigor and accessibility. It’s worth reading simply for the appendices, which feature a fascinating lay description of how hearing does (and does not) function in the human ear. For anyone who just can’t seem to wrap their head around the way sound works or how the tiny bones in the ear function—this is the book for you.

In an otherwise very insightful essay on the sense of touch in 2016, Adam Gopnik wrote that “perhaps the reason that touch has no art form is that its supremacy makes it hard to escape. We can shut our eyes and cover our ears, but it’s with our hands that we do.” Against this assertion, The Language of Light asks us—as Christine Sun Kim’s work does more directly—to think of sign language as an art form in and of itself.

Alexander Ullman is a third year PhD student in the Department of English at UC Berkeley.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig