by Katherine Preston

Published by University Of Chicago Press, 2013 | 320 pages

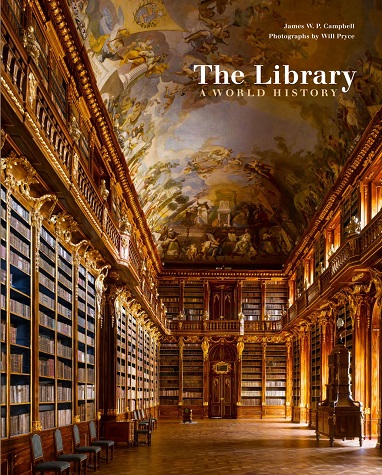

“Without libraries what have we? We have no past and no future.” So said Ray Bradbury, who wrote of a dystopian world without books in his novel Fahrenheit 451. In a gorgeous, if at times frustrating tome—illustrated with Will Pryce’s lush, glossy photographs—architectural historian James W.P. Campbell ambitiously attempts to document the glorious past, and speculate upon the uncertain future, of this sublime human institution.

Libraries can be divided into various types—academic, administrative, private, etc.—many of which have their roots in the ancient world. The first writing system—developed, it is believed, to record financial transactions—arose 5,500 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia. Early writings were captured on fragile, or unwieldy, materials—papyrus, clay—and the need was surely felt to organize and archive these documents. From early on rulers established libraries as means to both consolidate and expand their influence (star catalogues, for example, were used to chart the seasons for agricultural purposes), and demonstrate their political power to their citizens and rivals. The majestic Library of Alexandria, the most famous library of the ancient world, was created around 300 BCE by the successor to Alexander the Great, and lasted into the first centuries of the common era, when, legend has it, it was destroyed in an epochal conflagration (more likely it was destroyed gradually by a succession of secular (Roman) and religious (Christian and Islamic) enemies). Farther east, in Korea, wooden character blocks were devised around 1011 CE to print the Tripitaka Koreana, a central Buddhist text. The idea remained latent, however, until Johannes Guttenberg’s employment of a remarkably similar technology 450 years later, in the vastly different socio-economic setting of Early Modern Europe. In the following centuries innovations in printing technology and the declining cost of books led to exponential proliferations of knowledge and data, and ultimately to the emergence the modern scientific and industrial world. The modern public library as we know it—an institution that freely provides the broader public access to literature—appeared in the mid-19th century.

From its title—The Library: A World History—one would assume that Campbell’s history would dovetail closely with the history of knowledge. In addition, one would imagine the work would cover the diverse set of professions—librarians, scholars, patrons, etc.—who have played roles in the creation of this institution. The Library neglects most of this, and is instead considerably myopic in its focus on the history of architecture and the physical edifices themselves. True, it chronicles a protean architectural history (though even here it focuses overwhelmingly on the “high” and “monumental” constructions of the wealthy and powerful): from the ruins of multi-storied stoas (covered walkways) of ancient Greece to the sutra stores of Buddhist temples from the 11th century; from the gothic cloisters of the Middle Ages to the functional linearity and transparency of the modern age. And true, the physical structures of the ruins of libraries, as much as those of buildings which remain standing, do speak volumes as to the character and beliefs of those who would neglect, or preserve, them. Still, the degree to which the volume declines to provide a broader historical context is a significant shortcoming.

Throughout the history of the library key concerns transcended place and epoch: structure, iconography, function. But each era took on a unique and particular style specific to the materials and technology on hand, as well as that age's specific worldview. Some of the more interesting passages in the book concern the ways in which the mundane aspects of preserving books’ physical integrity —against, principally, mold, mites, and matches—have confounded librarians throughout the ages. In China, the mineral gypsum was placed beneath shelves to ward off dampness. Theft has likewise remained an enduring threat. In the Middle Ages and early modern period, books, which were often housed in monasteries, were regularly chained to the walls.

The images accompanying Campbell’s text complement and illuminate the details of the written history. Visually, the book is a jewel box of glossy photos. The sumptuous swirls of marble, gilding of gold, and the rainbow of Rococo frescoes recall the exquisite beauty of Faberge eggs. Campbell’s captions deftly illuminate architectural legerdemain invisible to an untrained eye: we learn, for example, that the stone elephant perched on a portal in the Biblioteca Malatestiana Library of Cesena, Italy, is a symbol of the Malatesta dynasty, whose motto was “The Indian elephant does not fear mosquitoes.”

In his preface, Campbell ponders the future of the library, and these speculations suffer as a result of his general neglect of immaterial facets of its history. He states, for example, that the library’s future will be as a museum for books that are curated, displayed, and preserved for posterity, and a workspace for the general public: “In a world in which space is expensive,” he writes, “free workspace is a popular attraction.” This is, of course, an astoundingly myopic reading of the library. Consider, for example, Wikipedia, or Google’s project of digitizing the world’s libraries. In his overlooking of the internet itself, beyond question the most influential library the world has ever seen, we see but one (albeit glaring) consequence of the fallacy of believing any history of the library, even a strictly architectural one, could neglect the immaterial aspects of that history.

If, as Campbell says, “the history of libraries has been a story of constant change and adaptation,” what then will be the future of the library? It has been said that WWI was the war of the chemists, WWII that of the physicists, and that WWIII will be the war of the mathematicians. That our world of algorithms and big data is swiftly becoming, if it is not already, the world of the mathematicians is beyond doubt. In this light, one could argue that the history of future libraries will chart not humanity’s conquest of knowledge, but rather knowledge’s conquest of humanity. Though Campbell chooses not to engage with the idea, one could argue that the history of the library even up to the present day is the history of this same process. It is even possible that the peculiar myopia of Campbell’s text may in fact be symptomatic of our unique historical moment, his text a Benjaminian flashpoint in the history of the library, “an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again.”

Nora Nunn is a PhD student in Duke University’s English department.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig