by by Margaret Kolb

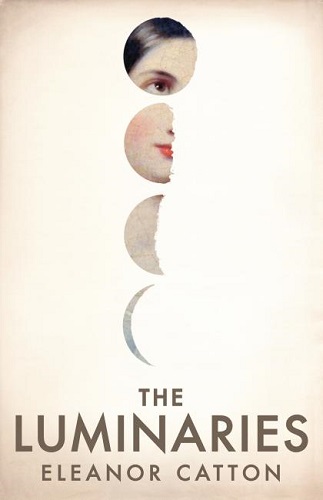

Published by Granta, 2013 | 832 pages

When Eleanor Catton’s neo-Victorian novel The Luminaries won the Man Booker Prize last year, the award made history twice-over: the text, clocking in at over 800 pages, is the longest work to have ever received the award, while Catton, at twenty-eight, became the youngest writer to have snagged the prize. And indeed, the novel is an extraordinary achievement. Set in the mid-1860s during the gold rush in New Zealand, The Luminaries is a detective-mystery that unfurls itself on a scale of immense, if not confounding, proportions. As the novel opens, a council of twelve men and one newly arrived interloper have gathered under the cover of darkness to investigate a series of strange events: over the course of one night, a prostitute has attempted suicide, a prospector has gone missing, and a hermit has been found dead with a stash of gold in his possession. The council’s task, and ours, is to uncover the facts of each case and to unearth the connection that exists between them—for we are given to understand that connected they must be.

To tackle these questions, The Luminaries mobilizes a cast of twenty characters to ply the reader’s senses with swashbuckling tales of shipwreck and buried treasure, forgery and blackmail, adultery and murder. Gold fever and opium dreams conspire, on a narrative level, to produce a sham of a séance, a trial scene worthy of prime-time television, and an old-fashioned story of star-crossed lovers to boot. It is, on the level of plot, a rollicking good time. And yet, reviews of the novel have been decidedly mixed. While Robert Macfarlane, the chair of the Booker judges who awarded Catton the prize, describes The Luminaries as “a novel you pan, as if for gold, and the returns are huge,” Kirsty Gunn, in an incisive review for The Guardian, calls the book “a great empty bag; an enormous, wicked, gleeful cheat.” “[T]he problem is that as we read on, we don’t read in,” Gunn writes, adding with particular sharpness, “It is a curious act of double-writing that Catton has achieved—that she could write more and more about a thing, only to have it matter less and less.”

If Gunn’s criticism—that the novel urges us to “read on” rather that “in”—strikes a chord, this is a consequence of the disjoint between the novel’s form and the reader’s function. Justine Jordan, in a review for The Guardian, offers a pitch-perfect précis of the former, observing that Catton

has organised her 800-page epic according to astrological principles, so that characters are not only associated with signs of the zodiac, or the sun and moon (the “luminaries” of the title), but interact with each other according to the predetermined movement of the heavens, while each of the novel’s 12 parts decreases in length over the course of the book to mimic the moon waning through its lunar cycle.But while Catton’s execution of her astrological plan on the level of narrative form is nothing short of masterful, the novel’s strict formal parameters come with a trade-off. Simply stated, a narrative structure derived from “the predetermined movement of the heavens” boxes the reader in, giving her the sense that it’s all been a priori charted for her, hook, line, and sinker. The result is a self-contradictory reading experience: The Luminaries is a novel that begs its reader to play detective while simultaneously thwarting that impulse; inevitably, the reader comes to feel herself less like a participant in the narrative and more like an onlooker tagging along for the ride. We can’t “read in,” in other words, because as we “read on,” there’s not much for us to do except, well, read. The Luminaries is so complex, so dexterously plotted that it leaves the reader wondering what’s left for her to do when confronted by a mystery that only its creator could ever solve.

And it’s not just that Catton’s novel exceeds the confines of the detective genre. As a number of reviewers have noted, in devising this immensely clever work, Catton bumps up against the limit-lines of the novel form as well. With a flourish, Gunn proposes that The Luminaries “[is] about what happens to us when we read novels—what we think we want from them—and from novels of this size, in particular.”1 Jordan, meanwhile, responds in a similar vein, observing that “…the reason the judges gave the prize to Catton…must be for its investigation into what a novel is, and can be. If a story is predetermined, does that change the way we read it? What are the consolations of fiction, and where do we find meaning: in personality or pattern, individual or structure? Such metaphysical questions underlie the confection of her plot.”

Implicit in both Gunn’s and Jordan’s readings is the sense that Catton’s neo-Victorian novel is concerned not just with exploring the boundaries of its genre, but also with reinvigorating us, its contemporary audience, as readers; in light of this, it ought to come as no surprise that the text brings with it its own brand of growing pains. Namely, if The Luminaries is a novel that undertakes to interrogate the novel form, then it does so by illuminating our present-day readiness to mistake the accumulation of information for the production of meaning (to use Jordan’s term)—in this case, by and within the text. In unraveling, step by step, the intractable conundrum it has set before us, Catton’s work delivers what we expect to get from detective novels—an account of whodunit and how—only to stir in us the inkling that this kind of knowing, the kind tethered to fact-finding and objective verifiability, might not actually satisfy. If The Luminaries is a novel about what it means to know, therefore, it is also a novel that makes us feel that “knowing,” taken as an endpoint in and of itself, doesn’t quite suffice.

Insofar as The Luminaries does develop a theory of how we know—an epistemology of detection—this theory amounts to the proposition, delivered by the novel’s detective-figure Walter Moody, that “to know a thing is to see it from all sides.” After all, from all sides is how the reader comes to “know” the solution to the mystery that the novel has staged—by entering into the experience of all the novel’s characters, each of which is brought into and out of the spotlight as that master-sleuth of a third-person narrator sees fit. Perhaps it ought to come as no surprise, therefore, that from the moment the narrator steps in to revise and order each personage’s fragmentary story so that it fits within the narrative as a whole, something is irrevocably lost. By way of example: as the novel sets the stage for the blustery Thomas Balfour to dive into his account (“I shall endeavor to acquaint you, Mr. Moody, with the cause of our assembly”), the novel breaks off into a new chapter, where we are assured that we are to be delivered into better hands than his:

The interruptions were too tiresome, and Balfour’s approach too digressive, to deserve a full and faithful record in the men’s own words. We shall here excise their imperfections, and impose a regimental order upon the impatient chronicle of the shipping agent’s roving mind; we shall apply our own mortar to the cracks and chinks of earthly recollection, and resurrect as new the edifice that, in solitary memory, exists only as a ruin.Here, the ethical imperative of fiction-reading—that of entering into the mind of another and meeting it on its own terms—is undercut by that all-knowing narrative voice that “appl[ies]…mortar to the cracks and chinks of earthly recollection.” In being decreed to be “[un]deserv[ing]” of “a full and faithful record in the [man’s] own words,” Balfour’s “solitary memory” is co-opted and reduced to a mere building-block of the larger narrative structure of the novel as a whole. Essentially, Catton gives us an either-or choice, and then makes the decision for us: the knowledge we gain about the facts of the case is secured at the expense of our access to the characters who are bound up in it.

If there's anything that the novel ultimately makes clear, however, it’s that this faith in the capacity to see things from all sides doesn’t suffice. In the end, the effect of this “mortar-to-the-cracks-and-chinks” method of narration is to turn the novel’s large cast of characters, none of whom is given substantially more page-time than the rest, into a collection of personages whose deepest longings and most trivial desires are all made to carry the same weight. Catton’s characters only take the stage to the degree that they relate to the mystery at hand; anything that lies beyond its bounds is a priori excluded. Take, for instance, one of Catton’s most finely wrought characters, the spineless bank clerk Charlie Frost, who receives an unexpected thirty-pound commission from the sale of the dead hermit’s property, only to have it suddenly revoked:

The receipt of this banknote had a sudden and intoxicating effect upon Charlie Frost, whose income was devoted, in the main, to the upkeep of parents he never saw, and did not love. In a frenzy of excitement, unprecedented in his worldly experience, Frost determined to spend the entire sum of money, and at once. He would not inform his parents of the windfall, and he would spend every last penny on himself. He changed the note into thirty shining sovereigns, and with these he purchased a silk vest, a case of whisky, a set of leather-bound histories, a ruby lapel-pin, a box of fine imported candies, and a set of monogrammed handkerchiefs, his initials picked out against a rose.This account of Frost’s childish shopping spree is as much a portrait of interiority as any we find in Catton’s novel. It is an ironic portrait painted from a distance, with a pure gold nugget—the offhand observation that Frost doesn’t love his parents—tossed in for good measure. The comic effect is augmented when it turns out that the sale of the estate is to be revoked and Frost stands to be liable for the money he has squandered: “He would be forced to go to one of Hokitika’s many usurers, and beg for credit; he would bear his debt for months, perhaps even for years; and worst of all, he would even have to confess the whole affair to his parents.” That a grown man’s greatest anxiety is getting in trouble with his parents is, of course, ridiculous, and pitiful, and maybe even a little bit tragic—but we’re not given an inside lane into his tragedy. “Is it worthwhile to spend so much time with a story that in the end isn’t invested in its characters?” Gunn asks.2 In seeking to shine its light from all angles, the novel raises a related question: does the view from everywhere end up being a view from nowhere at all?

In the end, what The Luminaries points to are the spaces between. In the movement from one character’s narrative to the next, the novel gestures toward what’s lost when we take human complexity and reduce it to knowledge to be gained, a mystery to be solved. The abysses between minds are not as easily soldered, Catton demonstrates, as the holes in a case. So, perhaps instead of striving “to see…from all sides,” we might take clergyman Cowell Devlin’s pronouncement as the novel’s latent mantra: “If I have learned one thing from experience, it is this: never underestimate how extraordinarily difficult it is to understand a situation from another person’s point of view.”

It is the gap between knowing and understanding that Catton, with her behemoth of a text, brings into focus. In making us harried solution-seekers long to know less (of the plot) so that we might understand more (of life), Catton’s novel confronts us with a rhetorical question: is it the job of the novel to show us how to know, or must it also teach us to understand? The latter, of course, is by far the more exacting enterprise: if knowing seeks out certainty, then understanding embraces indeterminacy; understanding comes without roadmaps or guarantees; it rejects totalities and mistrusts endpoints. In short, understanding lives in the space opened up by knowing that we can’t always know, and it takes comfort in the fact that meaning always amounts to more than the sum of its parts. If Catton plies us with knowledge “from all sides,” therefore, this is in order to inspire us, in the face of knowing’s insufficiency, to yearn for something more. Her point is well taken. In his 1884 essay “The Art of Fiction,” Henry James writes that “there is as much difference as there ever was between a good novel and a bad one: the bad is swept, with all the daubed canvases and spoiled marble, into some unvisited limbo or infinite rubbish-yard, beneath the back-windows of the world, and the good subsists and emits its light and stimulates our desire for perfection.” The Luminaries isn’t a perfect novel, but it is a good one—it is a novel that whets our appetite for more to read in hopes that we might thirst for more to understand.

C. A. Ciobanu is a Ph.D. candidate in English at Duke University.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig