by Katherine Preston

Published by Harvard University Press, 2015 | 632 pages

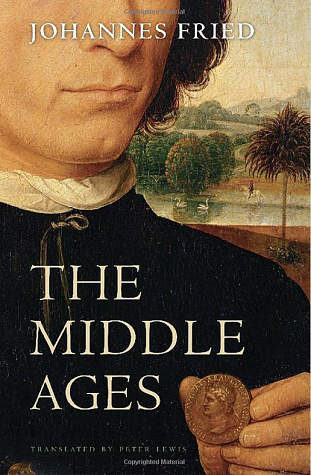

The cover of Johannes Fried's The Middle Ages, which features a detail of Hans Memling’s Portrait of a Man Holding a Coin of the Emperor Nero,hints at the rich cultural history of the late Middle Ages. Through its subject's act of displaying a coin of the Roman Emperor Nero, Memling’s (1430 – 1494) painting evinces the continued fascination with, and influence of, the ancient world on the period. On the other hand, the appearance of the coin takes on a different register when considered in light of the resurgence of trade and the emergency of the nascent capitalism of the period. Likewise, the pastoral beauty of the background landscape reveals the renewed interest in the physical world of the period, and points forwards towards the naturalism of the Romantic period. A more traditional history of the period would likely have use a more thoroughly Medieval work: perhaps the relative primitivism of a Romanesque fresco, or the anti-realism of a Byzantine icon or illuminated manuscript. The choice to use a Memling painting for the cover here is quite purposeful and apt, for Fried’s history is one that investigates the Middle Ages in all its rich complexity, looking backwards to its roots in the classical world, and forwards towards its legacy in modernity.

As its name suggests, the Middle Ages – which spans the fifth to the fifteenth centuries CE –is generally regarded as a “middle” period in history, sandwiched between the, it is implied, more historically consequential periods of the classical and Modern. As legend has it, poet and scholar Francesco Petrarch (1304 – 1374) “discovered” the Middle Ages via his discovery of Cicero's letters while rummaging through the archives of a monastery one day. Before this moment, the traditional history goes, the Medieval mind knew only itself, and thus lacked a true understanding of history. With Petrarch’s discovery of a civilization of immense learning and power that existed and then vanished over a millennia earlier, the modern age of subjectivity and uncertainty arguably began.

From the moment of its conception, the Middle Ages was construed as a period of decline. In their rediscovery of the humanist (Virgil’s Aeneid) and scientific (Euclid’s Elements) masterpieces of the classical age, early Renaissance Humanists rejected the past millennia as a period of abject barbarism. In 1602, Roman Catholic Cardinal Caesar Baronius dismissed the period not only as a “middle age,” but as a “dark age,” a term that most, even today, would recognize as connoting the Middle Ages. For centuries scholars dismissed the period as one of degeneration, and looked only to the classical and the modern in their studies of the histories of knowledge, technology, and more. Immanuel Kant was particularly critical, describing the Middle Ages as "childish and grotesque".

There were very real historical factors that encouraged this interpretation. The early Medieval period began roughly in the fifth century, with the fall of Rome and the barbarian invasions. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, a confluence of events converged to set Europe back in many ways. Depopulation and deurbanisation set in, currencies were devalued to the point where trade was reduced to barter, and literacy was lost for all but the most elite. The period was plagued by unceasing warfare, prompted by the often monstrous exultations of the Christian Church (“Time and again,” Fried writes, “promising new life through the Gospels but visiting death upon certain communities, Europe’s Latin Christendom revealed itself to be a ‘persecuting society’”), and, as the expected dark highlight of the chronicle, by the cataclysmic horror of the Black Death. At the very beginning of the period, St. Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430 CE), foreseeing the hardships that were to come, stressed in his The City of God Against the Pagans for the de-valuation of life on Earth in preparation for the consolations of the afterlife. In many ways, Augustine’s otherworldly brand of Catholicism emerged as the ascendant worldview of the period, as people looked towards the next life for reprieve from the hardships of this one.

Augustine’s worldview, however, was not the only one that influenced the period, and in recent times, scholars of the Medieval period have begun to re-evaluate the accomplishments and innovations of the period, and indeed to see it as foundational to modern thought. German Medieval historian Johannes Fried’s magnum opus The Middle Ages , an account of the evolution of the intellectual, artistic, theological, legal, managerial and proto-scientific ken of the period, is the most recent addition to this re-evaluation. He focuses on what he calls the "cultural evolution" of the Medieval era, and traces a continuous path of a culture of reason from the classical, through the Medieval, into the early modern period. The Renaissance, in this view, inherited a unique worldview perceptibly colored and benefited by its Medieval heritage, and is in fact a culmination of trends already underway in the Medieval period, rather than a rebirth of purely classical thought.

*

Fried's cultural historiography begins with Boethius (480- 524 CE), who lived in the court of a barbarian king, and contributed to early Medieval education and philosophy. Boethius’s introduction of the classical Greek quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy into Medieval Europe was to form the basis of intellectual education throughout the period. Fried charts the rise of Christianity, particularly with the authority of Gregory of Great, whose liturgical reforms helped define the Church of the Middle Ages. With this growing interest in Christianity came the establishment of monasteries across Europe, which became important learning centres and would prove crucial in the preservation of countless classical texts. As the centuries pass the new forms of political and economic organization arose: manorialism, the organisation of peasants into villages that owed rent and labour services to the nobles, and feudalism, the political structure whereby knights and lower-status nobles owed military service to their overlords in return for the right to rent from lands and manors.

The High Medieval period began around 1,000 CE when a number of key changes aligned to support travel, trade, and exploration. Technological and agricultural innovations enabled the rise of manufacturing, higher crop yields and production, while the Crusades reopened the Mediterranean to trade and travel. Centralised nation states emerged with kings at their head, reducing crime and (local) violence but making the ideal of a unified Christendom more distant. The recapture of Toledo, Spain, from the Muslims in 1085 led to the rediscovery of many classical texts, perhaps most importantly, at first, the works of Aristotle. His writings were incorporated into Medieval Catholic philosophy in a movement known as scholasticism, a philosophy that emphasised reconciling faith to reason. Around this time the first European universities were founded. The theology of Thomas Aquinas, the paintings of Giotto, the poetry of Dante and Chaucer, the travels of Marco Polo, and the architecture of Gothic cathedrals such as Chartres are among the outstanding achievements of this period.

The Late Middle Ages suffered a convergence of calamities including famine, plague, and war, which significantly diminished the population of Western Europe; between 1347 and 1350, the Black Death killed about one third of Europeans. Controversy, heresy, and schism within the Church paralleled the international conflict, civil strife, and peasant revolts that occurred in the kingdoms. But the ideal of reason inherited from the Greeks and sustained (if perhaps partially unintentionally) by the Church fathers and scholastics was not extinguished, and would blossom into a new world when the devastation of these years subsided.

*

Fried’s perspective in The Middle Ages celebrates the achievements of the Medieval period in all its forms, reaching beyond the familiar battles and monarchs of traditional histories, and engages deeply with the evolving landscape of ideas of the period.All the customary subjects in any history of Medieval times – the warring of kingdoms, the disease, the sieges, the feudal castes, the scholastics of monasticism – are included and well-covered. Such a monumental undertaking within a mere 632 pages is not without its tradeoffs, however, as such a vast array of topics can only receive a cursory treatment in a book of this size. Still, an exhaustive treatment of the immense diversity of materials here would take thousands of pages, a significant shortcoming in its own right.

The Medieval period was, Fried argues, "more mature and more wise, more inquisitive, inventive and with a finer feel for art," and its people "more revolutionary in their deployment of reason and their thinking" than we give them credit for. Ultimately, the ideas of the Middle Ages would culminate in the early modern breakthroughs of Copernicus and Kepler. A new world was being born, aware of its historical contingency, a world of uncertainty, power, and freedom.

Curtis Runstedler is a Ph.D. student studying Medieval Literature at Durham University. His research focuses on the moral implications for magic and medieval science in late medieval poetry and literature.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig