by Killian Quigley

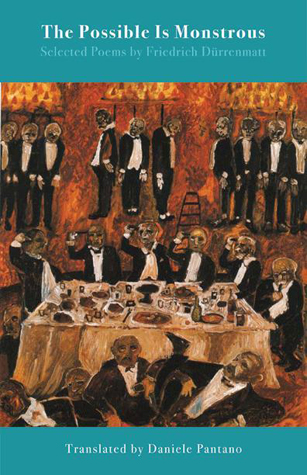

Published by Black Lawrence Press, 2010 | 216 pages pages

Over two decades after his death, Friedrich Dürrenmatt remains known as Switzerland’s greatest twentieth-century playwright. His plays are avant-garde staples. He’s also a confirmed part of the Western mainstream: in the sixties, one of his most successful works (The Visit) was made into a film starring Anthony Quinn and Ingrid Bergman. Dürrenmatt is praised for a brand of aesthetically and socially unsettling comedy: irreverent, discomfiting, virtuosically slapdash. Much of what makes his plays instantly recognizable as dark humor is their disconcerting, near-cacophonic polyphony. This polyphony comes from how many characters he tends to juxtapose but also from the way these characters fall in and out of different genres or conventions—occasionally even breaking into song—and from the sheer gaudiness of color and prop detail with which he insists on spattering his staging.

Comparatively more focused and monophonic, Dürrenmatt’s poems—of which The Possible is Monstrous gives a representative selection—at once echo his plays’ relentlessness and test the limit of their comically cynical voices. With no stage or interlocutor to offset them, his personas strike notes that the plays would rarely sound without irony: melancholy, helplessness, disappointment, guilt. These are surprising tones, and sometimes they seem to give you greater insight into Dürrenmatt as an artist and a thinker. They showcase Dürrenmatt’s horror at what he sees as our lack of discernment, the simultaneous voracity and blandness of our perceptions and desires. But at other times these poetic experiments fall a little flat. They tip too far into pathos or diagnosis, too far away from the irreverent, comedic lightness that otherwise makes Dürrenmatt’s work so poignant.

At his best, Dürrenmatt hypnotizes. His long poems are propelled by lists and repetitions that feel at once very regular and unnervingly unfocused. They stun you into a steady beat, but also make this stunned state feel shallow and blinding, unable to contain all of their represented worlds’ stray pieces or even properly to appreciate their diversity. In “Minotaur” Dürrenmatt has the monster’s labyrinth walled with mirrors: so that we always see dozens of Minotaurs killing, chasing, dancing. The Minotaur cannot at once appreciate both his world’s coherence and its richness—he either oversimplifies what he perceives or is baffled by it. The way Dürrenmatt recounts his story puts readers in a similar position: however we try to piece this refracted narrative together always seems too inattentive to anything but the broadest contours of this myth, too basic to help us navigate around any of this represented world’s specificities. Dürrenmatt presents these reductions and confusions as failures of vision on the Minotaur’s part, as well as on ours. It’s as if our rage for order kept vulgarly simplifying his world until it is entirely washed of color, whittled and polished beyond all sense of texture—without thereby making it any less chaotic.

Dürrenmatt diffuses his poems’ pathos into such uncomfortable, overwhelming blandness quite marvelously when writing about food:

The giant luce still caresses my thoughts like a distant lover, cooked in red wine and filled with lake trout, vendace, Blaufelchen and sour olives, pickled mushrooms, pearl onions and gherkins. All this pleased my stomach like a woman’s hand.Just this short fragment is nauseating—and much more precedes and follows it. Dürrenmatt makes you feel repulsed at how much you have apparently tried to bolt down all at once, at how poorly you can discriminate among these different potentially desirable dishes when they are mentioned to you in such multitudes, at such a rapid pace. Your attention is drawn not to these entrees’ specific appeals but to the undiscerning voracity you’ve just been lured into step with. Dürrenmatt renders this voracity even more repulsive by likening it to lechery. As he puts it in another poem, “There’s never been a cheaper collapse.”

At times Dürrenmatt is also able to condense this effect into a single stanza, as when he caps a long poem about repetitive-sounding comedians by stating:

But of course, each wave does resemble each other, and so did these actors as Dürrenmatt described them. This seems a fault of our attentiveness, not of sea waves’ and persons’ lack of particularity; and it’s not a fault Dürrenmatt gives us the means or even the hope of mending.Each of these comic actorsis great because he’s irreplaceable,No wave resembles another.

The poems quoted above are among the volume’s most performative pieces. Dürrenmatt is less successful when, almost against himself, he becomes aphoristic:

This stanza states up front the kind of philosophy poems such as “Minotaur” rhythmically illustrate. But eloquent as it is, the statement falls a little flat. It’s as if Dürrenmatt has let himself be defeated by the blandness for which he chastises his readers; as if he were mocking not our belief in our sensory sensitivity, but his own attempt to write a sensitively particular poem. The self-criticism, if that’s what this is, feels almost solipsistic: there’s little we as readers can partake of or engage with. In other such excessively condensed poems Dürrenmatt lets his disdain for the contemporary world run down what feel like mental shortcuts, into outbursts of anger indifferent to whether or not the reader will join in. These less successful poems are full of stars, Swiss banks, “electric brains” that “calculate” the world “without us,” elitist clubs, old ladies who hold too much social power. Though many of his personas claim to be speaking in a hurry, you have the sense that you are made to linger with them for a little too long: that there’s not enough depth and complexity in these persons, whether this depth be comic or tragic, to warrant the intensely attentive half-sympathetic, half-repulsed engagement they demand.The possible is monstrous. The addictionto perfectiondestroys most things. What remainsare splintersthat have been filed at needlessly.

As a counter-voice to Dürrenmatt’s plays, The Possible is Monstrous is food for much thought. The juxtaposition sheds much light on the way he achieves his effects of comic numbness, dispersion, and revulsion, as well as on the philosophy behind them. But those who already know and love these plays will probably most readily appreciate this collection also because these poems are as remarkable for their successes as they are for their comparative weaknesses or failures. Daniele Pantano, Dürrenmatt’s translator, does a good job of capturing his bitter, overwhelming language. If anything, the translation sometimes seems to veer a little too much into the aesthetically pleasing, especially in Dürrenmatt’s lesser poems.

Marta Figlerowicz is a graduate student in English at the University of California, Berkeley. Her criticism and creative writing have appeared or are forthcoming in, among others, Film Quarterly, New Literary History, The Journal of Modern Literature, Qui Parle, Dix-huitieme siecle, Prooftexts, Romance Sphere, The Harvard Advocate, and The Harvard Book Review.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig