by Killian Quigley

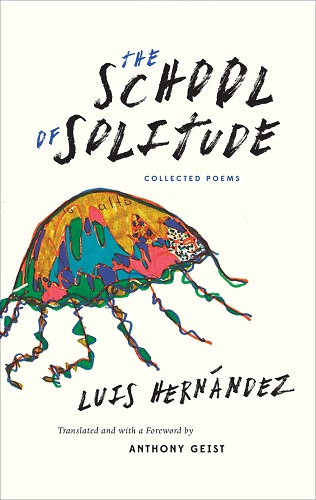

Published by Swan Isle Press, 2015 | 167 pages

Luis Hernández’s poem “[What’s that Flower]” begins whimsically with the four-line refrain to the sappy 1972 Tanya Tucker song “Delta Dawn”:

As the poem progresses the song’s refrain recurs as if in chorus, intermingled with a description of the pianist Shelley Álvarez playing Chopin. Tucker’s “Delta Dawn” is as stylistically different from Chopin as one might imagine. And yet it is precisely in this juxtaposition that “[What’s that Flower]” functions. Hernández repeats the four-line refrain throughout the poem, thereby adding both a quirky expressiveness and an improbable lyricism. While not semantically linked in any way, the refrain resonates somehow with the emotion of the pianist. “[What’s that Flower]” ends with the following lines:What’s that flowerYou have onCould it be a faded roseFrom days gone byAnd perhaps it will speak to you of me.And perhaps it will sayShelley Álvarez was feeling sentimental. This strange state only rarely overcame him.

And affect disturbed him stylistically. One afternoon, moved by these feelings, he left off a B-flat notation and recalled a certain sorrow: but the Prelude gained something: that must be how Frederic Chopin dreamt it in Palma de Mallorca: What’s that flower you have on.In the end, the two discourses have merged into a moving vocalization of sorrow.

Peruvian poet Luis Hernández (1941 - 1977) published three astonishing poetry collections by the age of twenty-four. From the publication of his final volume until his mysterious death twelve years later, he continued to write, but his life was plagued by drug addiction and he never published again. His later writings were largely comprised of notebook jottings – poems, drawings, musical notations – that he distributed freely among friends, family members, other poets, and strangers he met in bars.

Hernández kept no record of his unpublished writings, and in the decades since his death, an immense scholarly labor has been undertaken to discover and archive his oeuvre. The resulting collection resides in various private and public institutions, mostly in Peru. The School of Solitude, translated by Anthony Geist and recently released in a bilingual edition by Swan Isle Press, provides U.S. audiences with an excellent introduction to the work of this celebrated, enigmatic poet.

Hernández’s poems feature disjointed syntax, unexpected diction, and the intermingling of vastly different subject matters. Many of the poems in The School of Solitude challenge conventional notions of authorship. Frequently he excerpts from other texts without bothering to acknowledge (or hide) the sources. His “Things Incompatible with Nietzsche,” for example, is comprised almost exclusively of lines plagiarized from Nietzsche. He begins another poem with an epigraph, attributed to Aristotle, which makes anachronistic reference to a composition by Richard Strauss.

While this resembles much postmodern work, Hernández isn’t interested in deconstruction. His interest, instead, is in coherence, or, at least, in approaching coherence. While he continually undermines traditional elements of sense making, he employs other means, especially repetition and humor, to create alternative forms of meaning. Playfulness and the desire to push boundaries are always in the forefront, but what makes his work notable is his use of these elements to express underlying emotion.

The poem “[This Is Luisto Hernández]” demonstrates Hernández’s imaginative balance of disorientation and emotional resonance. The first half of the poem, which features multiple shifts in perspective, tone, and voice, offers little insight into what is important to the speaker or to the poem. However, Hernández’s use of syntax does offer some stability: the word “and” joins the opaque thoughts as though all are part of the same argument.:

Toward the end of the poem, Hernández shifts to three short pastoral descriptions, each repeating Christ’s admonition to forgive those who wrong us “seventy times seven” times. The following description ends the poem.This is Luisito HernándezFormer welterweightChampionAnd they asked him:How many timesMust we forgiveAnd he repliedSeventy timesSeven.And becauseI’ve been stabbedIn the backI know whereI’m going. And my heartStill chooses you

Hernandez offers no explicit connection between forgiveness, the landscape, and what lies deep in the speaker’s heart. But the invocations of landscape and forgiveness wash over the poem, even if the dramatic arc is more felt than understood.. . . OverThe hierba there isWind and prairiesHeldBy the silent hillsAnd he answered themSeventy times

The centerpiece of The School of Solitude is a series of eight consecutively numbered elegies addressed to a mysterious “you.” This person, while never identified, is clearly a loved one no longer in the speaker’s life. These poems recall small, intimate moments. There is no praise of the deceased, no solace for the living, no finality at the end in these elegies, only loss. In “Elegy Number One,” the speaker recalls a time they spent by the sea:

The writing is disjointed but the sentiment is direct: memories of a time with the beloved by the sea intertwine with expressions of love and loss.You toyed with omensCast by water in the wornPlumbing and with kelpOn the silent pierOh, take me with you,I who recallYour ways of smilingAnd your eyesAnd with the kelp

Hernández’s characteristic repetition recurs not only within individual poems but throughout the entire series. An idea in one poem is picked up and extended in another; entire passages are repeated or reworked. The effect is to give the impression of obsessive longing, of memory ceaselessly finding itself returning again and again to contemplate the absent beloved.

Which is to say that these poems enact a grief that cannot be contained or dissipated. In this sense, although the poems are called elegies, they actually function to expose the inadequacy of the elegy, with its traditional air of finality and completeness.

Distributed throughout The School of Solitude are photocopies of Hernández’s handwritten poems and drawings, all done on lined school notebooks. They provide a sense of the physical form of the poem’s original renderings, as well as Hernández’s free, unconventional spirit. Luis Hernández believed not only in challenging and complicating poetic conventions within his work; he conducted his entire life as an expression of this belief. With this publication of Anthony Geist’s excellent translation of The School of Solitude, Swan Isle Press has presented a great gift to English reading public. We should receive these poems with the same warmth and joy as did those friends, family members, poets, and strangers to whom they were originally given.

Mike Puican has had poems in Poetry, Michigan Quarterly Review, Cortland Review, and New England Review, among others. His poetry reviews have appeared in Kenyon Review, Another Chicago Magazine, and TriQuarterly. He won the 2004 Tia Chucha Press Chapbook Contest for his chapbook, 30 Seconds. Mike was a member of the 1996 Chicago Slam Team and for the past ten years has been president of the board of the Guild Literary Complex in Chicago.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig