by Killian Quigley

Published by Knopf, 2010 | 50 pages

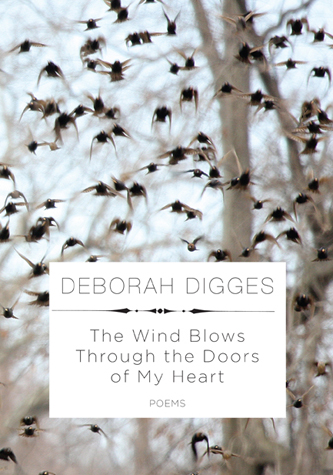

The Wind Blows Through the Doors of My Heart follows closely upon Deborah Digges’ death. Digges—an established American poet, the author of several prior award-winning books—had not finished revising and collating what would thus be her final manuscript. This task was completed for her by editors the volume’s introduction leaves anonymous. Sadly appropriate to its timing, The Wind Blows Through the Doors of My Heart records a work of grief and mourning. The poet undertakes these emotional labors towards her recently deceased loved ones, but they also seem to prepare the reader for processing the loss of the poet herself.

Most of the volume’s central concerns are announced in its title poem, The Wind Blows Through the Doors of My Heart, which is also the first poem of the collection. Digges describes her heart as a many-roomed house. The house is plagued by twin forces of motion and stillness, metaphors for two ways of experiencing a loved one’s loss. A “wind” is blowing into the house, throwing it into disarray and arranging its broken pieces into a new order centered around a missing presence. This wind “blows all my candles out” and “smashes birds’ nests.” At the same time, it “rakes the bedsheets as though someone/ had just made love,” turning what had been a tidy, self-contained room into a chapel of nostalgia. Some spaces this wind cannot penetrate; they are “the rooms of the dead.” These rooms are locked in a stillness that can no longer endure change but—for that same reason—can also no longer be inhabited by either the deceased person or by the house’s owner herself. Locked between these two options, the house becomes a map of two (e)motions of grief: turmoil and paralysis. The painful process of reorienting one’s life around a loved person’s loss is balanced against an unwillingness to make any further efforts at life now that the loved person is no longer there.

Poems that follow continue to work through these two aspects of grieving. Throughout, a careful tension is maintained between perseverance and despair, between attempts at making sense of the poet’s loss and urges to give in to a traumatized helplessness. The poems veer between the abstract and the episodic. “don’t cut your hair,” one of the more abstract poems of the collection, juggles mythologies and folk beliefs: comparing the lonely woman at its center to a sailor’s wife, a sailor, a siren, a fallen Eve, a fertility goddess. On the other end of this spectrum, “the coat”—one of the most moving pieces in the collection—describes a single poignant moment: a walk the poet takes in her deceased husband’s hospital clothes.

Digges’ most successful poems, such as “the birthing” and “the haying,” manage to stay on both levels of generality at once, domesticating mythology within a specific memory or event. “the birthing” opens with a quasi-religious incantation and goes on to describe the poet and her husband saving the life of a birthing calf. This rescued life hauntingly counterpoints the poet’s impending helplessness in the face of her husband’s illness:

“the haying” weaves the rupture made by the husband’s death into a detailed account of rural flora and farm work, dramatizing the disparity between the poet’s continued presence in the rural life cycle and her sense of dissymmetry without her husband by her side: “I have lain down across such orchard grasses on your grave/ smelling the deep that keeps you, tasting snow.”

Throughout, Digges’ tone is a sparse sincerity, at once dignified and vulnerable. She uses a pared-down vocabulary whose quirks come primarily from the natural world. Her uneven but generally long line is broken orally rather than visually, by pauses in breath meted out slowly like a cantor’s or a storyteller’s. Her strengths come not from formal experimentation or verbal flourish but from the simplicity and intense directness into which she manages to condense her lyrics; from the intimacy she manages to achieve without falling into emotional exhibitionism.

Not all the poems collected in The Wind Blows Through the Doors of My Heart were complete at Digges’ death. Interspersed among highly condensed, polished pieces are ones that seem looser and less self-aware; ones whose emotions are suddenly much rawer, or which—on the contrary—tangle in relatively uncombed metaphoric language. This unevenness does not compromise the volume, but it does make itself felt: if only as a regret that Digges had not had the chance to bring all of these pieces to the high standard many of them so successfully achieve, a speculation about what shape the collection would have taken had that chance been given to her. As her poems instruct us to do, it allows us to experience Digges’ death as it quietly echoes through the volume as both a movement and a stasis, a rupture her poetry keeps outlasting and one that must leave us questioning and helpless.

Marta Figlerowicz is a graduate student in English at the University of California, Berkeley. Her criticism and creative writing have appeared or are forthcoming in, among others, Film Quarterly, New Literary History, The Journal of Modern Literature, Qui Parle, Dix-huitieme siecle, Prooftexts, Romance Sphere, The Harvard Advocate, and The Harvard Book Review.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig