by Surya Bowyer

Published by Publication Studio, 2011 | 80 pages

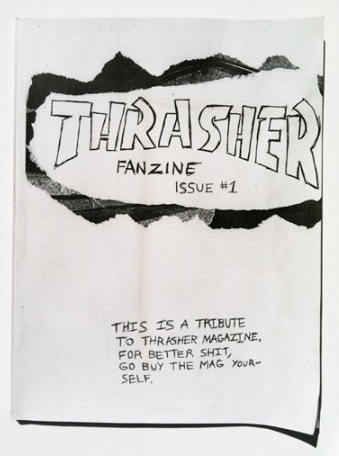

In Thrasher Fanzine, Sam Korman and Israel Lund have taken an innovative approach to the slow-burn genre of skateboarding retrospective: effacing the traditional function of editor/curator altogether. A ’zine-style book composed solely of unmediated photocopied highlights from old issues of seminal skateboarding magazine Thrasher, Lund and Korman’s book collection contains no original material at all except for their printed byline and a hand-drawn cover proclaiming in scribbled caps: “THIS IS A TRIBUTE TO THRASHER MAGAZINE. FOR BETTER SHIT, GO BUY THE MAG YOUR-SELF.” This is no nostalgia-washed memoir of a bygone Golden Age of Skateboarding or glossy reissue of iconic underground photography brushed up and made respectable by mythologizing captions or celebrity prefaces: Thrasher Fanzine is a pulp and ink wormhole linking twenty-first-century DIY revivalism to its eighties punk forebears. Thirty years ago the original Thrasher Magazine—now a publication with a circulation of more than 250,000 and a vibrant online community to boot—played a crucial role in fomenting the subcultural alliance between the worlds of punk rock, skateboarding, and street art that would eventually become a $2 billion lifestyle industry. Thrasher Fanzine, however, is less about the historical details of this evolution and more about lingering over the visual-photographic manifestations of a particular cultural moment and the force vector they represented for a generation of American youth. An authentic fanzine (despite a concession to the heavier, glossier stock of contemporary boutique publishing), Lund and Korman’s book is concerned with the Thing in Itself—not skateboarding, exactly, but classic skate images and their real-world materiality.

Skateboarding began as the spawn of surf culture in post-war California, but it wasn’t until the underground skate subculture of Santa Monica (Dogtown’s “Z-boys”) revealed itself to a wider public at the 1974 Del Mar Nationals that skating took on the trappings of its second incarnation: a brash countercultural attitude, new styles of banked and vertical riding, faster and more extreme techniques fostered by better board technologies like polyurethane wheels. In the skate press, the artist and photojournalist C. R. Stecyk III was the undisputed godfather of this new brand of skateboarding; the raw and revolutionary photo- and typographic vernacular of his “Dogtown” columns for Skateboarder magazine—lyrical, articulate, sneering, crypto-anarchist meditations on skate culture laid out with jaw-dropping photo spreads of Dogtown insiders, both on their boards and off—functioned as a voice in the wilderness for an entire generation of skateboarders raised in inland America. When the inevitable ebb-tide of the early eighties double-dip recession finally returned skateboarding to niche status, it was Thrasher Magazine—equal parts style guide, technical manual, ethnographic inquiry, and political manifesto—that took up the cultural and photojournalistic torch Stecyk had carried for the previous decade.

The true power and beauty of Thrasher Magazine is in its development of formal principles capable of transmitting the compressed intensity of skate sensibilities in its stapled pages. There is a true sense of violence—both troubling and potentially intoxicating—latent on nearly every page of Fanzine. Even beyond the raucous, confrontational attitude that manifests in the images and headline language (“$KATE FOR MONEY, DIE FOR FAME), beyond the possibility and reality of physical harm (“CARNAGE! SKATEBOARD INJURY BLOODFEST”), beyond the persistent sense of sheer social instability—childhood trauma? sexual violence? police brutality?—lurking just outside the frame in some of these floodlit, abandoned alleyways—there is the explosiveness of motion, the muscular tension and the impact of die-trying skateboarding itself and its equally violent capture in still photography. The slideshow sequences provide useful tutorials for the transmission and execution of a Bigspin Boardslide or a panoramic experience of the Little Haiti Stair Banks, but the real full-page showstoppers are all about amplitude, empty space, the as-yet-unrealized potential for acceleration, impact, pain, or sweet stuck landings. The arrest of the image paradoxically transmits its dynamism; the fisheye lens with the expanded center and vertiginous periphery collapses the distance between image and viewer. Lund and Korman’s Thrasher Fanzine, the fanzine of a fanzine, somehow amplifies that transmission even as it widens the distance it travels. We animate the arrested image, fill in the empty space not as ourselves but as the wrought-up adolescent through whose eyes we see it.

It’s easy to want to see this kind of production as symptomatic of a modern trend—call it a debasement of conceptualism—in which every artist is a brand, every idea a viable product. Still, it seems pretty clear that the curatorial impetus behind Thrasher Fanzine was less about making some dough and more about the desire to share something awesome. There is a distinctly analog feel to the book that differentiates it from its digital-born brethren, most clearly on display in its lack of an urge to comprehensiveness. Three decades of lossless-audio Grateful Dead soundboard rips or The Complete New Yorker Hard Drive this is not. The assorted cover images, spreads, and photo sequences that appear in Thrasher Fanzine—some wrinkled, some with visible tears and scissor-marks—hearken to an era of baseball cards with no plastic sleeves, of torn-out pages that accumulate scatter-shot patterns of pushpin holes as they get traded from bedroom wall to bedroom wall. On implicit display is the pre-aesthetic world of adolescence, where wear and tear is love and use-value reigns supreme. Each page or spread is a black-and-white Xerox of a color original, a degradation that adds rather than subtracts complexity—is that smear graffiti or blood?—and that holds up under the weight of close critical or loving scrutiny: the distorted posture that implies a trajectory, the spray-painted concrete that contains a history and a community.

Theoretically, much can be made of skateboarding as a generational orientation toward found-ness, toward space: the children who grew up skateboarding in the sixties and seventies—like their art-world contemporaries, the Situationists—approached the man-made urban environment in which they found themselves as a natural environment, replete with new kinds of resources and ripe for appropriation in ways that their original designers never would have thought possible. In a sense, this orientation was truly violent, disruptive of the prevailing categories of classification and the logic of means and ends. Today, with the rapid growth of “Landscape Infrastructure” as an urban-planning and architectural methodology, we are finally seeing the academic-institutional realization of the radical potential contained in that moment of violence. But before firms like the SWA Group began redesigning drainage canals and transmission corridors as urban waterfronts and linear parks, latchkey kids were transforming abandoned swimming pools and culverts into innovative gymnasia, arenas, and community hubs. As Stecyk famously put it in his first Dogtown column in 1975: “Two hundred years of American technology has unwittingly created a massive cement playground of unlimited potential. But it was the minds of eleven-year-olds that could see that potential.” Today, at thrashermagazine.com, the sidebar ad promotes an online bachelor’s degree in digital cinematography; Thrasher Fanzine is the product of an even younger generation for whom the world of images constitutes a new environment—the violence and the possibility of this new world we are still learning how to see.

Chris Catanese is a writer and editor living in Durham, North Carolina.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig