by by Margaret Kolb

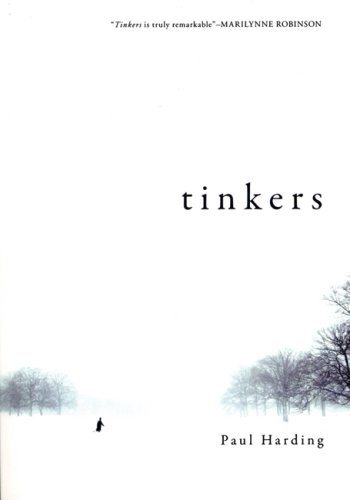

Published by Bellevue Literary Press, 2009 | 191 pages

Tinkers was Paul Harding’s first attempt to make a name for himself as a writer—and what a name it made him. His debut novel won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize, one of very few small-press publications ever to do so. It also received effusive praise from well-known novelists such as Marilynne Robinson and Barry Unsworth (both of whom taught Harding at Iowa’s MFA program). Tinkers is not an even novel, but its honors are well deserved. In spite of its lapses—which are primarily faults of lesser daring—it keeps our minds busy and brightened, held secure in the bubble of family memories it blows, then bursts, before its readers’ eyes.

Tinkers’ physical center is the dying body of George Washington Crosby. George is an elderly New Englander whose last lulls and agonies pace out the novel’s primary plot strand. Family histories—sagas, legends, instructions, anecdotes—flock towards the bedbound Crosby and flow out of him. The narrative shifts in and out of the first person, and from one mind to another—George’s, his father’s, his grandson’s—as we slowly, fragmentedly reconnect the dying man to his past and present and, more vaguely, to the future of the family he is about to fall away from. In its meanderings, Tinkers zeroes in most persistently on George Crosby’s relationship to his father Howard and on Howard’s life as it oscillates towards and away from George. Howard is an eccentric, suffering figure: an itinerant tinker, a failed poet, epileptic at a time when cures are sparse and the stigma considerable. George settles into a life much more staid and fastidious—juggling a daytime teaching position and an after-hours love of watchmaking. In his last days, he at once relives the instability of his childhood home and, through his illness, descends into a fragmented, helpless existence very much like his father’s.

In interviews, Harding fashions himself a transcendentalist. This is not inaccurate. He makes us yearn for a porous, spacious spirituality; for ecstatic experiences in which boundaries between particular human beings, or between a human being and his environment, are momentarily gone; for flashes of insight in which a person’s nature, or her attitude towards a loved one, is crystallized and definitively revealed. Yet, he also shows us, over again, that these lofty timeless states are unreachable. Throughout the novel every possible catharsis is frustrated. A young boy’s flash of pained sympathy roughens and coarsens as he tries to explain it to his grandfather. A hermit’s romantically secluded life is cut into by a grotesque, debilitating toothache. The characters’ and the reader’s ambition to grasp the Crosbys’ complex emotional economies is at once echoed and gently mocked in the confident expertise George puts into repairing a clock. Instead of climbing emotional heights characters fumble, withdraw, awkwardly shift their weight at ecstasy’s doorstep. Their moments of clarity are vulnerable and childlike. They bring these persons to understand not their depth but their smallness and frailty:

I should say that the sermons my father gave on Sundays were bland and vague. Parishioners regularly drifted off to sleep sitting up in their pews and it was common to hear snoring coming from this or that corner of the room. My father’s voice droned on about the importance of every little creature in the field. … There was no correspondence between these inept speeches with the passionate, even obsessive writing he did up beneath the pitched roof.This description of Howard’s father is almost allegorical of the novel’s overall tenor. It directly follows upon a more hopeful, near-transcendental moment. Sitting at the dinner table, the young Howard had glowed with silent admiration of his father’s mysterious, passionate writing process. He had fantasized about the father’s hidden wisdom, about his seeming ability to move beyond the ordinary reality of his family’s dinner table. In the eyes and ears of the congregation, this projected paternal universe contracts to a vulnerable introspective space. If we still feel for Howard and for his father—indeed, if we now feel for them all the more—it is because of how frail their emotional lives suddenly seem, how precariously tied to the quotidian present moment rather than the transcendence they hoped to anchor themselves in. We feel for them because of the unguarded pleasure and support they took from a small, easily smoothed fold of sensation: a pleasure and support we also, for a moment, partook of quite as needily as Howard himself. The novel’s aim is to accustom us to this affective pattern, gradually to make us accept such gentle anticlimaxes as the basis from which we, and the characters themselves, can come to grips with George Crosby’s death.

These emotional economies are consistent and moving; executed by Harding with as much humility and careful love as shines through his characters’ internal self-fashioning. If Tinkers occasionally wavers, it is because this affective and formal consistency is almost too firm, too self-restricting. In spite of the novel’s ostensible polyphony, we have the impression of being inside one mind only. A careful and beautiful mind, but one whose contours and emotional range remain the same; one always moved by the same order of detail, one whose desires retain the same structure in each character it voices even though the exact objects and conditions of its longing might be changed. This emotional uniformity is not implausible in realist terms. After all, Harding describes a series of related men raised in very similar circumstances. Harding also hardly attempts to hide this uniformity; even the idiom his novel’s many men speak is basically the same. Yet, as one keeps turning Tinkers’ pages, one does at points find oneself wishing for more: more verbal daring, more philosophical and emotional diversity, firmer—or more surprisingly porous—boundaries among the selves the novel draws. Or, if we are to remain within one mindset, one would want to see that mindset not only probe but also question itself. One feels this way especially since—though meticulously executed—Harding’s style is precise and self-effacing to the point of occasionally seeming impersonal, to the point of sometimes making it hard to hear a distinct person’s voice behind his sentences. Tinkers lacks little, if any, in craft and purposiveness. What one does miss is greater freedom, a more ambitious scope.

One only quibbles with Harding’s self-set limits, though, because one feels these limits are self-set; and because of how easily and deeply his novel draws us in nevertheless. If Tinkers is not yet a novel to knock the breath out of its reader, it is a work that promises its author might soon do so. While we still wait for further Harding novels to compare it to, it is an excellently crafted and engaging read on its own terms.

Marta Figlerowicz is a graduate student in English at the University of California, Berkeley. Her criticism and creative writing have appeared in, among others, New Literary History, Dix-huitieme siecle, Prooftexts, The Harvard Advocate, and The Harvard Book Review.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig