by Killian Quigley

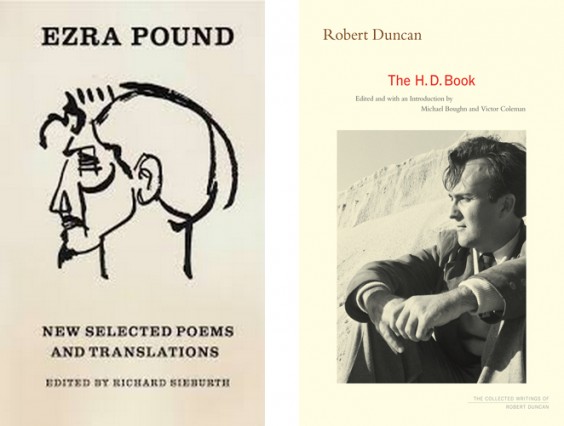

Published by University of California Press; New Directions, 2011 ; 2010 | 678 ; 391 pages

Robert Duncan's heresies are innumerable. Often overlooked in his poetry as the pardonable consequence of a theosophical upbringing, the publication of his massive scholarly appreciation of Hilda Doolittle throws light on the depth and extent to which the poet was committed to religious dissent and poetic nonconformity. Even those who have long appreciated Duncan’s poetry might be surprised to learn what this work shows him to have actually believed about his own art.

American poet Robert Duncan was born in 1919 in Oakland, California, to a mother who would die birthing him. With his father unable to rear the child, he was adopted by a family of practicing Theosophists. According to biographer Lisa Jarnot, the family selected him based upon astrological alignments for his time and place of birth, that his mother should have died after his birth, and that he should be of Anglo-Saxon Protestant descent. He was, it seems, chosen by this new family because he had been fated. His parents, deeply involved in the Western esoteric tradition, would interpret his dreams for him (reading his poetry, it would be interesting to know whether they were reading Freud or Jung for this), and predicted that he would witness a second death of civilization in his lifetime. Although he spent most of his career in and around San Francisco (he would later be lumped into “The San Francisco Renaissance” in Donald Allen’s seminal anthology, The New American Poetry 1945-1960), and was also a close friend and correspondent of Charles Olson, rector of the influentially experimental Black Mountain College where Duncan studied and taught, the California poet was singular in his commitment to hidden knowledge and the arcane tradition. Further alienating him from mainstream life, he was openly gay in the 1940s, publishing the pioneering essay, “The Homosexual in Society,” in 1944, fifteen years before the Stonewall Riots inaugurated the organized gay rights movement in America. Moving in bohemian socialist circles in the 1930s and 40s, Duncan was again singularly a Gnostic Anarchist. In his later life, his poetry would be gain worldwide appreciation, when published by City Lights Books and New Directions.

But, despite the efforts of the literary establishment to integrate Duncan into its reading lists, the remarkably puritanical attitude of literary studies remains challenged by this dissident and non-conformist. Canonizing Duncan already goes against the iconoclasm he struggled to advocate. Even his landmark scholarly study of H.D., which matches Hugh Kenner's monumental 1971 The Pound Era in scope and implication, is nevertheless filled with dreamy autobiographical reflection, opening with an account of the first poem he ever heard (the quintessential Imagism poem, "Heat," by H.D.). Bringing a memory of the high school teacher in Bakersfield who read it to him to bear on his lifelong feeling that poetry was a matter that "seemed to a contain personal revelation," he concludes that this teacher (Miss Keough) admitted, initiated, even baptized him into the mystical "rites of participation" in Poetry. Mingled with this conversion was the phenomenon of falling in love (with her and other teachers). And mingled with falling in love was "the communication of self." Poetry was from the outset about communicating personally with a kindred spirit. It was an interpersonal, if not an internuminal, art.

Poetry, Duncan believed, was ruled by a spirit that was manifest beneath or behind the imagistic poetics of H.D. and Ezra Pound. Pointing to their early interest in occult matters, he identifies and expounds upon an unrecognized tradition in 20th century American poetry: The Cult of the Image. Ezra Pound, who catalyzed the early 20c movement of Imagism, called for a poetry that was marked by its “luminous details.” Robert Duncan, reading the early Imagists, takes this luminosity to signify a supernatural element. He writes in The H.D. Book: "The concept of the eidolon inherited from Iamblichus in which primal and eternal images are the movers or powers of the universe, agents of reality, charged the poet[s'] reveries and visions with a radical purpose, a directive towards the heart of the matter. . . the waves throwing themselves down in ranks upon the shore." From Iamblichus to Plotinus to H.D. and Pound, Duncan traces a genealogy for the poet trucking in esoteric knowledge, a genealogy in which he is implicated. The orphan, he elsewhere suggests, must invent his own parents.

Having been raised in an occult tutorial, when Duncan became a student of the poet Hilda Doolittle (H.D.), he uniquely read her works as esoteric texts. For Duncan, Imagism had heathenish roots and magical potential: "The cult of the gods as it is found in the hellenizing poems of Lawrence, H.D., and Pound in the Imagist period cannot be separated from the reawakened sense of the meaning and reality of the gods in contemporary studies of the mystery cults." So it is that, with the rites of Imagism, "Gods float in the azure air." "'Image,' the 'intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time' was not simply an invention of the poet to convey vividly his impressions or sensibility in things but a form in poetry of trafficking with the daemonic and beyond the daemonic with the divine." Duncan’s Imagism was significantly more than descriptionism or “impressionism,” it was a religious persuasion with heretical underpinnings.

H.D. and Pound were implicated in what T.S. Eliot, in his suppressed lectures at the University of Virginia, considered chasing "after strange gods." Collapsing a xenophobic critique of religious heresy with one of poetic non-conformity, the Anglican convert attacked these pagan poets for precisely the reasons Duncan would later praise them. “What” Eliot later asks, “does Mr. Pound believe?" Pound's faith was akin to that which Duncan identified in H.D. and himself: The conviction that a poet could generate "a new dimension in which eternal companions appeared." In his search for Totemic Guides, Duncan reveals that the take which he has on twentieth-century Imagism is not only influenced by the Western esoteric tradition, it is also shamanistic in the tribal-primitivistic sense. In spite of the detailed history that he gives of theosophist Helena Blavatsky, her mystical circle and his adoptive family's association with that circle, the real gnostic teachers of The H.D. Book are H.D., Ezra Pound, and Sigmund Freud (and quietly Carl G. Jung). Interestingly, as for Eliot, Duncan finds that for this poet "even religious matters are literary in their character," and, notwithstanding that, of a lesser intensity even than they were with Miss Keough.

The links with shamanistic practice place Duncan in a group with which he seldom associated. He was, that is, also connected to Native American poetries. In his mind, Sigmund Freud was to H.D. as the Yaqui Don Juan Matus was to Carlos Castaneda, "H.D. being an initiate of Freud himself." But, whereas Don Juan's lessons on Nagual sorcery took place on the mysterious plane between "the world of ordinary people and the world of sorcerers," a plane that stretched from Sonora to the spectral Ixtlan, Freud's lesson for H.D. on unlocking the magical potential of trauma and Träume took place in a forbidden world of relations between psychotherapy and the Orphic mysteries. According to Duncan:

It is like a dream but not a dream, this going out into the world of the poem, inspired by the directions of an other self. It has kinship too with the séance of the shaman, and in this light we recognize the country of the poem as being like the shaman's land of the dead or the theosophical medium's astral plane. In the story of Orpheus there is a hint of how close the shaman and the poet may be, the singer and the seer.Further on, he quotes H.D. as she describes the Orphic point of entry: "Once a Dakota poet I knew said systematic starvation was a sort of dope. I don't mean we starved actually. But doing without non-essentials leaves room, a room. I walked into it here."

H.D.'s Freud was a starting point but, from here, Duncan draws out into more interdimensional environments. In his scheme, H.D.'s multiverse mysticism not only corresponds closely with the nature, forms, and interests of American shamanistic poetries such as ethnopoetics, it also has echoes in the fantastical work of Philip K. Dick, Ursula K. Le Guin and Robert Anton Wilson. Duncan's deep associations with the genres of Fantasy and Science Fiction are a somewhat forbidden relation. For instance, although in the early days of “The Berkeley Renaissance,” semanticist poet Jack Spicer and Science Fiction novelist Philip K. Dick were working on a Martian language together, the two are seldom thought of in the same light. Duncan likewise muses, twisting together Fantasy, Science Fiction, Poetry and Religious Esotericism: "In the teachings of theosophy this Astral Light was dreamland; but it was also fairyland or Wonderland. . . But if one could change the scale, that was the constant theme of theosophy, if one saw a "terrene" Mars in the String of Terra, in the String of Mars other planets, another earthly reality could appear." The heretical implication here being that to read Duncan in a serious way tests the limit against which readers are willing to have Science Fiction or Fantasy enter critical literary studies—or even just readerly appreciation. For Duncan, Mars is coterminous with the Dreamscape, the literary landscape and "the shaman's land of the dead." A study of one must be a study of all or, what he called, “a symposium of the whole.”

Of Duncan's self-confessed "suite of heresies" (some that I will not take the time to unpack include: Ascribing to Laura Riding's epigraph, "God is A Woman," while taking to task Robert Graves' softening of the same Female God into a White Goddess of dispirited benevolence; taking Ezra Pound's political anathemas on Douglasite Social Credit economics seriously, even going so far as to explore a mystical import in those ideas as they tie-in with the rites of the Image; flatly rejecting the presumption that literary criticism is anything other than an imaginative function; adding that that imaginative function is as intuitive and inexplicable as the writing of a poem; and in all this taking seriously a principle of play; etc.).

But the greatest of all Duncan’s heresies might have been to have even read H.D. at all. By the 1950s, H.D.'s reputation among the New Critical literary establishment had fallen to such lows that she had been removed from its influential anthologies, most notably Louis Untermeyer's Anthology of British and American Poetry, edited by Karl Shapiro and Richard Wilbur. Randall Jarrell had even concluded, "H.D. is silly in the head." "There were," Duncan remembers, "few who read [her] deeply." From the "burning or ridicule" by the "descendents of those ministers of the seventeenth and eighteenth century, holding out against the magic of poetry as once they had held out. . . against the magic-religion of witch-cults," Duncan steals H.D. And, in fact, recuperates her silliness, tracking an etymology for the “seely,” which once meant “blissful, holy; innocent, harmless; deserving of pity, helpless, defenceless; often of the soul, as in danger of divine judgment; frail, worn-out, crazy; foolish.” Saving holy H.D. from the fire, Duncan’s work is more than recuperation, it is heathenish act of defiance. The H.D. Book is the high blasphemy of literary genius that few have dared to achieve.

Duncan was not the first poet influenced by H.D. Ezra Pound's first book of poems was a hand-bound collection called "Hilda's Book," inspired by and dedicated to his love and muse between the years 1905 and 1907. Pound was a crucial invigorating force on 20c experimentalist poetry, leading a variety of movements, techniques and persuasions, including Imagism and Vorticism. He is also renowned for instantiating a world perspective for his poetry, with translations from Italian, Provençal, Anglo-Saxon, Greek, Latin, French, Spanish, Japanese and Chinese, bringing these and many other traditions into the expansive and controversial poem, The Cantos, of which the post war sections would be awarded the Bollingen Prize amid great controversy due to his wartime Fascist sympathies. Central to The Cantos’ movement across historical episodes and poetic traditions is what Pound called “the ‘magic moment’ or moment of metamorphosis, [the] bust through from quotidian into ‘divine or permanent world.’ Gods, etc.” Frequently comparing his poetry to a tree, its branches reached for celestial states with the elements of vegetation cycles flowing inside it, one can easily understand the significant influence he was to exert on Duncan.

Pound, in fact, started his career as a pagan nature poet. The Gnostic nature of Pound’s poetic reveries is precisely expressed by the early poem, included in the collection dedicated to his early love, H.D., "The Tree:" "I stood still and was a tree amid the wood/Knowing the truth of things unseen before." This poem opens Richard Sieburth's New Selected Poems and Translations, candidly placing Pound amid the same heritage of Gnosticism that brought about H.D. and, later, Duncan. The previous, and significantly smaller, Selected Poems of Ezra Pound (also published by New Directions) picked Pound up in a distinctly more masculinist troubadour aspect: "Bah! I have sung women in three cities,/But it is all the same;/And I will sing of the sun." That this aspect was constituent to Pound's poetics is irrefutable; yet the new organization and greater selection of poetry by Sieburth better conveys that it was an aspect and not an essence. In his poetry, Pound often wanders the valleys of 12c Provençe and, in the next moment, takes a turn into Jeffersonian political theory or a turn toward the alchemical formulas of the neoplatonic philosopher Marsilio Ficino. Sieburth's text carefully documents this variety of influences. This could surely be gleaned in the selection of Personae: The Shorter Poems of Ezra Pound, but that selection excludes the massively important Cantos and many of the translations that the new selection gainfully includes.

In addition to offering more poems and more different kinds of poems than even Personae, the New Selected, like Sieburth's previous editorships of Pound's The Pisan Cantos and A Walking Tour in Southern France, offers a substantial critical apparatus in the form of notes and essays. (This is a student's edition of a poet before whom most people are students.) The appendix of essays focuses on the challenges of selecting Pound, written by three of his selectors: Sieburth, Eliot, and John Berryman. They transmit a sense of the range of Pound's poetry and thought, whetting a reader's appetite for a similarly more curated and comprehensive selection of Pound's prose than is currently available from the same publishing house. Thumbing through Donald Gallup's 1983 Ezra Pound: A Bibliography, a student can measure how much Pound published against how little actually goes into shaping the popular opinions of the poet. Most of this published material is available in the massive Ezra Pound's Poetry and Prose: Contributions to Periodicals in Ten Volumes, but an expanded and annotated student's version of such a publication is yet to be seen. This is not to mention the large amount of unpublished poetry and prose that he left behind that remains unpublished. In this sense, Sieburth's work may still not quite be adequate.

That being said, Sieburth's editorship of the poetry and translations will be a useful addition to the libraries of both inveterate and newer readers of Pound. The New Selected Poems and Translations should be a welcome addition in the study and enjoyment of one of the twentieth-century's most technically versatile and profoundly knowledgeable heretics. Taking Duncan's spiritual ethos as my own, here, at least, I will say that it is gratifying to see a Pound gathered, like the limbs of Osiris, into "the soul-boat up out of the carnal and psychic mire into 'the body of light come forth from the body of fire.'" The body of poetry available to a reader at a given moment is the point source for personal communication with a kindred spirit that is made luminous in its details, of which both The New Selected Poems and Translations of Ezra Pound and Robert Duncan’s H.D. Book take great care.

Edgar Garcia’s poetry, translations and essays have appeared in a number of publications, including Damn the Caesars, Jacket2, Mandorla and Sous les Pavés. Author of Mayan Texts: A Galactic Birth Canal (Burnt Water Press) and Boundary Loot (forthcoming, Punch Press), he is also an editor of Hydra Magazine and co-curates the blog nagualli.blogspot.com. He is completing a PhD in American Literature at Yale University.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig