by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Mariner Books, 2012 | 125 pages

Given their rarity, feral children appear to possess an inordinate amount of significance in our culture. From childhood to adulthood, we are fed stories of feral children—like Mowgli (The Jungle Book), Tarzan (Tarzan of the Apes), François Truffaut’sL’Enfant sauvage, and “Genie,” the real-life feral child who was found by a social worker after having been held in solitary confinement for ten years. The portrayal is a reliably romantic and sensational one. The idea of a child raised in nature, by animals, who inherits the best of the human—language, compassion, uprightness—and of the animal—strength, ferocity, loyalty—has become both the object of popular lore and fantasy.

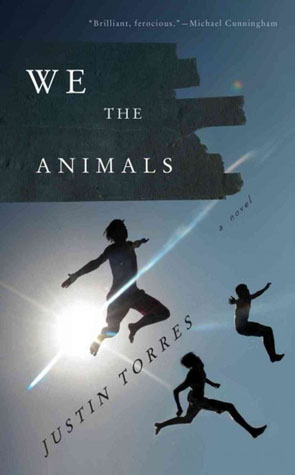

Justin Torres’ We the Animals, an autobiographical coming-of-age story about three brothers growing up in a dysfunctional household, challenges readers to reconsider their romanticized notions of children as innately wild things who have a privileged relationship to the natural world. While the novel’s cover, which features three shirtless boys soaring across a sun-filled sky, nods towards the more playful and fantastical possibilities of the child-as-animal motif, Torres’ story soberly reminds us that feral or wild children are in fact the product of neglect and abuse. The child’s ability to survive and sometimes even thrive in the animal world, he suggests, may instead be more accurately read as a reminder of how thin the line between child and the wild actually is.

The border between parents and children, children and animals, and parents and animals is constantly blurred in Torres’ novel, both in the scenes as they unfold and in his sparse but lyrical prose. Within the first seven pages of the novel, it becomes apparent that the “We” in “We the Animals” refers not only to the children, but to their parents as well. The father, “Paps,” beats his sons—Manny, Joe, and the unnamed narrator—until their little round butt cheeks are “red, raw, leather-whipped.” The mother, “Ma,” is described as a “confused goose of a woman” who cannot tell the difference between Monday and Sunday, or night and day. She tells her children, “I hate my life,” causing her son Joel to cry, and her other son Manny to punch Joel in an attempt to silence him. One of the most tender and joyous moments the family spends together occurs in the bathroom when Paps and Ma make love on the sink while their children play in the bathtub.

We learn that the narrator’s mother was only 14, and his father only 16, when they had their first child, dropped out of school, and were married. The unexpected pregnancy is initially framed as a failure of education. The narrator states, “No one had explained sex to Ma when she was a kid—not the nuns at school and not her own mother.” Without knowledge, Ma is easily fooled by the teenage Paps who is only interested in satisfying his own teenage sexual desire. When the fourteen year old Ma “asked Paps, ‘Can’t I get pregnant from this?’ Paps had lied.” This ignorance Ma tries to remedy for her own children by sitting them down on the carpet and opening the encyclopedia to “Reproductive Systems,” showing them “cross-section diagrams of penises and vaginas and how they fit.” Ma’s innocence paradoxically leads to her devolution into a more adult and yet animalistic state, a transformation she simultaneously embraces and resists. As a “teen mom,” Ma finds herself trapped between worlds. The ability to reproduce distinguishes the child from the adult, just as the ability to control reproduction distinguishes the human from the animal, a fact made explicit when Ma commands her children to “make” her “born” by pretending to give birth to her. The children proceed to dress Ma in a raincoat so that she can keep her clothing clean as they spray a bottle of ketchup in her face to simulate the blood that covers a newborn baby’s body. When the ketchup covered Ma falls to the floor, the children scream “It’s a mom!”

It is perhaps unsurprising that the narrator struggles with his own development as an adult and sexual being. The family’s discovery of the nature of the narrator’s sexual experience constitutes the climax of Torres’ novel. The narrator has always been the outlier in the family. Of the three brothers, he is the most intellectually gifted, a point which his parents often comment upon. His book smarts bring his parents great pride until they discover the ways in which he uses writing to explore his darkest sexual fantasies. However, his parents’ emotional and sexual immaturity has left him with no one to turn to except his journal as a means to explore and articulate the person who he understands himself to be. In this way, We The Animals is something of a meta-text, a deeply affecting piece of writing about the expressive and emotional power of the written word.

Torres’ story is told in a series of carefully curated snapshots of memory from his childhood. Each set off in its own short chapter, we hear about the time his father bought a truck against his mother’s wishes (“Big Dick Truck”), how the family celebrates their half Puerto-Rican, half white background in (“Heritage”), or the time the narrator learns how to swim (“The Lake”). The chapters are for the most part ordered chronologically, though Torres does not make any obvious attempts to connect them beyond the thematic level. His resistance to narrative at times feels like an attempt to unsettle the Western bildungsroman tradition, and in this sense the structure and style of the novel is reminiscent of other Ethnic-American semi-autobiographical “first” works like Sandra Cisneros’ House on Mango Street (1984) and Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior (1975). Cisneros’ and Kingston’s text are also told in a series of episodic chapters, some shorter, some longer, that are linked thematically, but that could also be excerpted and read on their own as short stories. Torres’ work seems indebted to the works of these pioneering female authors from decades past in a way that makes the experimental qualities of his novel appear to be much more conventional within the tradition of Ethnic-American literature. Torres’ text may leave the reader wondering if the most experimental thing an autobiographer can do today is write a traditionally structured and compelling first-person narrative.

Nonetheless, like the best pieces of literature and the best works of autobiography, We the Animals challenges the reader to investigate what it means to be human and what it means to grow up in, quite imaginatively, the most literal way.

Jeanette Tran is a scholar of early modern literature who also enjoys reading contemporary American fiction. She currently resides in New York.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig