by by Margaret Kolb

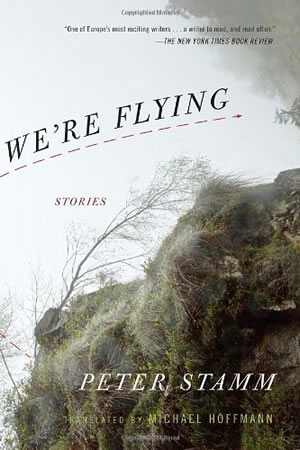

Published by Other Press, 2012 | 370 pages

Peter Stamm’s fiction shows no small degree of scorn towards its likely reading demographic. His subject is the average individual: average in age, class standing, talent, and ambition. With only a few exceptions, the men and women portrayed in We’re Flying live mediocre lives, possess mediocre talents, and pursue equally mediocre careers as academics, ministers, artists, and even organic vegetable farmers. Nobody is particularly wealthy, nobody is particularly successful, and nobody is really in love. Their lives all feel a bit pre-fabricated, and are furnished (literally and symbolically) by Ikea.

The overall tone is one of judgment over bourgeois condition and aspirations, which, We’re Flying implies, simultaneously impose delusions of grandeur and shut off the possibility of their realization. Shakespeare’s King Lear explored the dilemma of “accommodated man" over 400 years ago, and the conflicts that Stamm’s characters find themselves embroiled in suggest that not much has changed since then. Stamm’s text investigates the process by which, having satisfied our basic need for clothes, food, and shelter, we thereafter turn away from our fellows and towards maintaining a base material comfort for ourselves. It remains hard for those who live amongst comfort and convenience to experience empathy and to take professional, emotional or spiritual risks for their own sake, let alone for the sake of others.

Heidi (“Three Sisters”) wants to go to art school, but loses her nerve when she realizes that all of her abstract drawings resemble nothing more than a “load of cunts.” Unsure about her future, she enters an unhappy marriage with Rainer and has a child named Cyril whom she regularly abuses. Weschler (“Years Later”) returns to his hometown hoping to gloat about his success following a scandalous divorce from his first wife, Magrit, 20 years ago, but becomes upset when he learns that Magrit has died and no one has bothered to inform him. Alice (“The Natural Way of Things”) is irritated when a couple with two noisy children rent the home next door and disturb the peace and quiet of her summer vacation. She comes to regret her annoyance only after a freak accident ends the children’s screaming and laughter forever.

“We’re Flying,” the collection’s eponymous story, is about imagination, how imagination could in theory lead to empathy, and why it so often fails to do so. Angelika is a daycare worker who is stuck watching Dominic after his parents are late to pick him up at the end of the day. The school has presumably implemented measures to discourage this typical parental behavior – fines, the general shaming of the parents, even possible expulsion from the daycare – but these obviously have not worked. Angelika has a date, and because she cannot leave the child standing outside of the daycare alone, she brings him home with her. When her date Benno arrives, he plays with Dominic and the two get along swimmingly. Dominic climbs on Benno’s back and they imagine that they are flying.

This kind of imagination—this ability to imagine that one is flying when one is in fact sitting still, this ability to imagine that if someone picks you up, to help you fly, that this person will not drop you—is something that “We’re Flying” suggests only children and men who have remained stuck in a state of arrested development can access. Angelika, a professional childcare provider, finds it impossible to relate to Dominic in the way that Benno does, and wonders if “she could ever manage to offer a child such a home. It seemed to her she didn’t have the confidence, the security, or the love.” When the parents finally pick up Dominic, they give Angelika an obviously regifted bottle of expensive perfume as a thank you present. The story ends with an aroused Benno walking towards Angelika with a bulging erection, but instead of articulating her fears to him, she excuses herself to go to the restroom where she locks the door and sobs on the toilet.

As in Stamm’s other works, sexual anxiety and dysfunction play a key role in his characters’ (lack of) personal development. Sexual dysfunction appears so frequently throughout We’re Flying that it becomes almost banal; these stories are, arguably, about the banality of sex, of sexual anxiety and dysfunction. In Stamm’s stories, sex stands for the things that we feel we can’t talk about, and therefore don’t talk about, out of shame and guilt, or out of fear that we may expose ourselves as monstrous. In “Expectations,” the first story in the collection, we meet Daphne and Patrick, a May-December couple whose relationship is never fully consummated. We are never told why Patrick will not have sex with Daphne, and Daphne never asks. The story ends with Daphne, alone, fantasizing about Patrick having sex with her while she inaudibly whispers to him through the ceiling to “come” to her.

“Seven Sleepers,” which appears near the end of the collection, portrays perhaps the sole occasion in the collection where a man, instead of running, hiding, or letting a woman walk away, actually says something. Alfons is a lonely organic vegetable farmer who meets Lydia at a music festival that he has allowed to take place on his property. The two appear to have genuine chemistry, another first for the collection. Lydia accepts Alfons’ invitation to stay in his guest bedroom instead of driving back to the city after the concerts are over. When Lydia exits the shower wearing Alfons’ t-shirt, Alfons panics and offends Lydia by replying to her flirtations with an uncalled for gruffness. Lydia tells Alfons that she has clearly made a mistake, and that it is best if she goes home after all. Here, the story breaks off from the pattern that has been established throughout the rest of the collection. Alfons, seeing that her eyes are moist, “went up to her, wiped the tears away with his thumb, and kissed her, first on the forehead, then on the mouth. Don’t go, he whispered. I don’t want you to go.”

King Lear ends with the injunction that we must “Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.” This seems like a simple enough prescription for the avoidance of future tragedy, but, as Stamm’s stories demonstrate, the path of least resistance is often the one in which we say whatever we think we ought to say to maximize our own comfort. By forcing his readers to witness and inhabit the discomfort that mars his characters’ lives, Stamm powerfully illuminates the ways in which self-preservation too often amounts to nothing more than a life of cynicism, pain and loneliness.

Jeanette Tran is a scholar of early modern literature who also enjoys reading contemporary American fiction. She currently resides in New York.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig