by Deborah Harris

Published by MIT Press, 2016 | 288 pages

On December 24, 1968, while in lunar orbit aboard the Apollo 8 spacecraft, astronaut Bill Anders snapped one of the most iconic photographs of the twentieth century. The 'Earthrise' photograph – with the “ground” of the moon’s surface in the foreground, and the earth floating in the distant above as if itself a moon – heralded a post-nationalist perspective of the globe, from which it would be possible to rethink the plight of humanity as a shared affair. From the vantage point of 2017, the iconic “earthrise” photograph is as likely to elicit anxiety as it is cosmic exultation. Of late, the image is perhaps most frequently deployed as an emblem of the planet’s imperiled status. New York Magazine, for example, ran a version of the image on the cover of its “Doomed Earth Catalog” July 2017 issue, in which the earth is pictured in dried up shades of brown and grey rather than the familiar marble of blues and greens.

That same year, 1968, saw the publication of the first issue of The Whole Earth Catalog (WEC), a compendium of articles, essays, and product reviews published by Stewart Brand and associates. Contrary to popular opinion, the 'Earthrise' photograph did not, in fact, adorn the cover of the first edition WEC, though it would become a symbol of that publication when it was included on the second edition. A publication issued regularly between 1968 and 1972, WEC was printed in oversized tabloid format (27.5 cm by 38.5 cm) in Menlo Park, California. The only specimen of the catalog genre to ever win a National Book Award—Brand and his staff received their prize in the “Contemporary Affairs” category—WEC offered in-depth reviews of eclectic and ostensibly revolutionary books and merchandise.

As one earlier reviewer put it, The Whole Earth Catalog was a “Space age WALDEN.” It’s an apt description. The publication was quite Thoreauvian. In its ecological outlook, of course, but also, interestingly, in its structural layout, where it deploys Thoreauvian textual divisions. While Thoreau divided his texts into categories such as “Economy,” “Reading,” “Sounds,” “Visitors,” “Higher Laws,” “Brute Neighbors,” WEC was divided into nine sections: Understanding Whole Systems, Land Use, Shelter, Industry, Craft, Community, Nomadics, Communications, and Learning. If Thoreau sought to write a speculative, and in many ways piecemeal “operators manual” for how one might better live on the margins of society, so, too, did WEC.

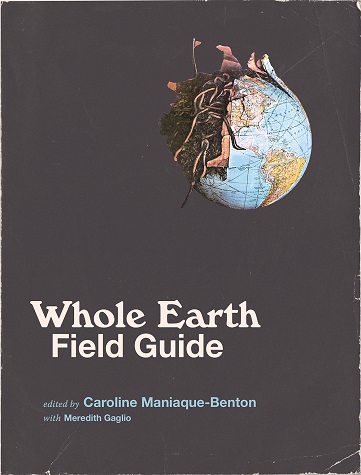

The Whole Earth Catalogue appeared at a revolutionary moment in American culture. WEC, with its ecological outlook and emphasis on self-sufficiency, DIY, and holism, epitomized that historical moment. As Neil deGrasse Tyson has put it, it’s no coincidence that WEC and its signature earthrise image appeared at a galvanized moment of increasingly global ecological awareness: indeed, the years of its publication saw the passage of the "Clean Air Act," (1970), the first Earth Day (1970), the foundation of the EPA (1970), the foundation of Doctors without Borders (1971), the Clean Water Act 1971, and the banning of DDT (1972), to name but a few specific developments. Like the “earthrise” photograph, the Catalog was immediately perceived to be a cultural touchstone. In his 2005 Stanford University commencement address, Steve Jobs referred to it as "one of the bibles of my generation." With time, however, The Whole Earth Catalogue’s fame has decreased, and today few are familiar with it. In their innovative new anthology The Whole Earth Field Guide, published by MIT University Press, Caroline Maniaque-Benton—Professor of History of Architecture and Design at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture Normandie, and the author of the previous volume French Encounters with the American Counterculture 1960-1980 (2011)—and assistant editor Meredith Gaglio aim to bring renewed attention to this significant text, delivering a compendium of eighty curated excerpts from WEC, as well as a useful array of context and assessment.

The Maniaque-Benton volume gathers together excerpts from the final edition of The Whole Earth Catalog, and provides a comprehensive bibliography. Instead of reviews of the sort supplied by the original catalog, Field Guide provides actual excerpts selected from the advertised texts. Not surprisingly, many of the readings contained in the volume represent recognizable greatest hits from texts circulating in the counterculture of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Highlights include selections from Richard Buckminster Fuller, Aldo Leopold, Norbert Wiener, and John Muir. The volume also provides a section on the history of WEC’s production, which is inflected by archival discoveries from Brand’s personal papers in the Special Collections of Stanford University Libraries and includes a selection of photographs of life at the office of WEC.

Crucially, Maniaque-Benton’s Whole Earth Field Guide is not exclusively devoted to its function as an anthology. Instead, considerable attention and analysis are devoted to WEC’s historical status as a pioneering “new media” text. Steve Jobs, for example, in the same commencement address cited above, described The Whole Earth Catalog as "sort of like Google in paperback form, 35 years before Google came along." Field Guide is one, though certainly not the first, of a series of recent academic treatments that investigate the ways in which WEC functioned as a precursor to the internet. Perhaps most notably, in the influential 2006 study From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism, the critic Fred Turner suggested the structure and content of the WEC, not to mention its influence on its early Silicon Valley readership in its hometown, directly foreshadows the “sociotechnical genesis of the internet.” Turner put the WEC on the map for a generation of new media scholars.

Where Manique Breton’s volume breaks new ground is by challenging the tendency within recent critical works of presenting Brand as a progressive icon and exemplar of the radicalism of the hippies, free-thinkers, and activists of the late sixties and seventies. Viewed in a nostalgic mood, the snapshots early in the volume of WEC staff (in bell-bottoms) enjoying their daily, lunchtime volleyball game can appear quaint, even utopian. But when interpreted by Maniaque-Benton as precursors to the mandated morale-building exercises of contemporary corporate life, these and many other aspects of WEC – the office culture at WEC, not to mention Brand’s military-style leadership and WEC’s ruthless, product-oriented business model – come to be seen as presaging the rise of techno-capitalism. For Maniaque-Benton, WEC cannot be detached from the consumerist, corporate structures of which it was inevitably a part, and which arguably problematize its ostensible political agenda.

So where, exactly, does the Field Guide fit into the broader legacy (and legend) of Brand and The Whole Earth Catalog? Insofar as Field Guide appeals as a surrogate or simulation of the original, the relationship between Field Guide and WEC might be described as skeuomorphic. One the one hand, Maniaque-Benton’s anthology not only responds to WEC, it all but functions as a belated supplement to the Catalog. Consider, for example, how Field Guide’s oversized 8 X 10.5 formatting, which while not quite as large as WEC’s, openly invites the reader to consider the volume a work of nostalgia. Maniaque-Breton permits us to be nostalgic about the physical object of WEC as well as its culture. On the other hand, however, and simultaneously, Field Guide Field Guide sheds light on the ways WEC not only exemplified, but even pioneered, innovations that brought about the modern techno-capitalist world. Indeed, regardless of whether or not we should assume a direct legacy between WEC and the present-day culture of Silicon Valley and internet consumerism more broadly—what lines, for example, can be drawn between Brand’s volleyball lunches to the complimentary heirloom kale salads and annual ski-trips to Tahoe provided as part of the hiring package for the twenty-first-century lords of Google and Apple and Genentech—a version of the ethical crisis embedded in the project of WEC surely occurs for us every time we order a book from Amazon, even if that book is Walden, or the Marx-Engels Reader. Or The Whole Earth Field Guide.

With The Whole Earth Field Guide, Maniaque-Benton examines The Whole Earth Catalog as a historical artifact, providing a complex glimpse of WEC’s literary innovation, as well as its problematic participation in the cultural logic of techno-capitalism. Ultimately, the most fascinating aspect of Maniaque-Benton’s volume is the way it highlights the paradox of the WEC: the fact that it is simultaneously an ecological landmark and a pioneering innovation in marketing and technological capitalism. Uncertainty regarding the best means of evaluating WEC’s historical legacy looms over Maniaque-Benton’s volume: how much authentic radicalism, for example, should we attribute to the rhetorical gestures of these catalogs of progress and social engineering? To what extent should we read them as archives of progressive innovation, versus consumerist and industrial/technological innovation? The new Field Guide succeeds precisely because it offers the reader an encounter with WEC as an instrument of both promise and paradox.

Kevin C. Moore is a lecturer in the Writing Program at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He earned his PhD in English from UCLA in 2013. His scholarly and creative work has appeared in journals including Writing on the Edge, Arizona Quarterly, Composition Studies, Souciant, as well as several edited collections in literature and rhetoric. His research interests include nineteenth- and twentieth-century American literature, writing studies, and the rhetoric of creativity. He is currently at work on a novel titled The Dog Massacres.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig