by by Margaret Kolb

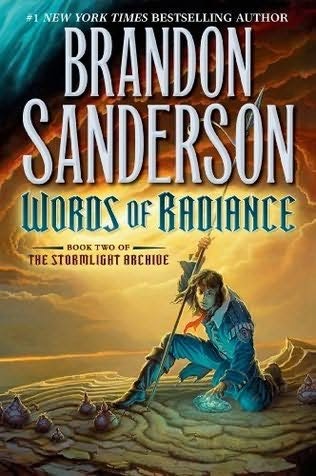

Published by Tor, 2014 | 1087 pages

Brandon Sanderson, as fantasy readers know, was the author brought in to finish Robert Jordan’s epic series The Wheel of Time after Jordan’s death in 2007. The Wheel of Time, begun in 1990 and finished by Sanderson last year, was massive both imaginatively and textually, and was arguably the most important fantasy series since The Lord of the Rings; as Edward Rothstein wrote, in an oft-quoted line from a New York Times review, Jordan came “to dominate the world Tolkien began to reveal.” In particular, the scale of Jordan’s imagination took the genre a step beyond Tolkien’s work: his elaborate alternate mythology (based on Celtic traditions) and complex magic system, along with a complex network of political and historical details, formed the backdrop for a massive epic that took fourteen volumes to resolve. The Stormlight Archive, Sanderson’s own new series, is clearly influenced by Jordan’s approach to the fantasy epic form. Sanderson has said he expects the series to be ten books long, and they are no shorter than their Wheel of Time forebears; similarly, one of the major delights of the series is simply experiencing the depth of imagination in Sanderson’s alternate world of “Roshar.” The plot of the novel, the second in the Stormlight Archive, picks up immediately where the first book of the series, The Way of Kings, left off. Dalinar Kholin, one of the ten highprinces of the country of “Alethkar” and the uncle of the Alethi King Elhokar, is stepping into the role of “Highprince of War.” This position gives him de jure dictatorial control over all of Alethkar’s military forces, though he does not have, in a crucial plot point, de facto control. The novel’s second protagonist, the former slave Kaladin—rescued from certain death by Dalinar at the end of The Way of Kings—finds himself caught up in Alethkar’s political turmoil through his role as the leader of Dalinar’s and eventually Elhokar’s bodyguard. But the novel ultimately focuses on the third emerging protagonist of the series, the young scholar and artist Shallan Davar. Just as Sanderson built The Way of Kings around Kaladin through retrospective interludes on his past interspersed with the main plot, Shallan’s memories of her family recur regularly throughout Words of Radiance. Moreover, Sanderson gives Shallan the speech expressing most clearly the ethic of resilience and self-control that forms one of the major themes of the series. At one point, Kaladin and Shallan find themselves in conversation alone together; Kaladin having accused her of being shallow, Shallan speaks of “The crushing guilt of being powerless. Of wishing they’d hurt you instead of those around you.” Kaladin’s subsequent reaction to Shallan’s remark stands in, I think, for Sanderson’s and the book’s attitude towards the character: “He saw it in her eyes. The anguish, the frustration. The terrible nothing had clawed inside and sought to smother her. […] She had been broken. Then she smiled. Oh storms. She smiled anyway.” Crucially, then, Shallan’s constant humor is not a sign of shallowness at all: it is a form of confrontation with despair. Having known desperate sorrow, Shallan consciously chooses to be humorous, denying the sadness power over her life. Words of Radiance is thus in part a bildungsroman, with this dynamic as its central thread: it will be Shallan’s challenge to develop maturity, confront the secrets she has repressed out of psychological necessity, and find a way to integrate them with her self in a way that doesn’t “break” her. Perhaps more striking even than the three interlocking stories of Dalinar, Kaladin, and Shallan is the novel’s metaphysical thoughtfulness. The Way of Kings revealed that the world of Roshar is filled with ethereal entities called “spren,” which are quite commonplace: there are emotion spren, for instance, who drift around people anytime they feel an emotion particularly strongly, and entities like “rotspren” and “rainspren” which seem to respond to physical events. In addition, Kaladin’s acquisition of magical powers—he can manipulate gravity—turned out to depend upon his development of a relationship with an “honor” spren named Sylphrena. Shallan, speculating about spren with her mentor early in Words of Radiance, guesses that they are “living ideas”: her mentor agrees, explaining that they are “concepts that have gained a fragment of sentience,” or “elements of the Cognitive Realm that have leaked into the physical world.” Indeed, the spren that has attached itself to Shallan concurs with this explanation: while Shallan gets magical abilities out of her spren, the spren itself gets “sapience”—spren come to humans because they are “Ideas that wish to live.” It’s easy to miss Sanderson’s philosophical cleverness here. One truism, upon which Descartes relied, holds that you can’t have a thought without a thinker. “I think, therefore I am” is supposed to be axiomatic because we infer the existence of someone thinking from the evidence of a thought. But Friedrich Nietzsche pointed out that there’s a buried assumption in Descartes’ view: really, all one can infer from “I think” is that “thinking is going on.” Whether that thinking is localized in an entity one might call a self, and whether that offers sufficient evidence of the existence of “selves,” requires—Nietzsche argued—further assumptions about what thoughts and selves are. Sanderson depicts physically Nietzsche’s metaphysical point: spren are ideas independent of a thinker, and they attach themselves to humans to be thought—which lets them, in an interesting metaphor, “live.” Of course, the structure of a universe where this is possible would have to be somewhat different from our own, and it is to Sanderson’s credit that his texts go to some length to elucidate the laws underlying it. The reader learns that there is a sense in which the world of Roshar is one of philosophical idealism. I refer here to idealism in its metaphysical rather than its ethical register: the term describes a tradition, descending from George Berkeley in English thought and Kant in German thought, which holds that there is no physical world, or at least that if there was we could never access it. All there is that we can know are the “ideas,” or representations of the world, that exist in our minds. To illustrate how Sanderson does this, consider that one of the immediate problems idealism must overcome is the fact of agreement: the reason we can agree, for instance, that a table has the shape it does would seem to be the fact that there is actually a physical table there, whose properties do not depend on our perception of them. This consistency, Shallan’s spren explains, is not because of any physical law: instead, “because people have considered it, long enough, to be a table,” it maintains the shape of one. “It becomes truth to the table because of the truth the people create for it” (308-09). In other words, the matter maintains its shape because of the stability of our perceptions, not the other way around. There is, however, nothing permanent about this stability in The Stormlight Archive; in fact, one of Shallan’s magical abilities is “soulcasting,” the ability to turn one substance into another. This ability involves arguing with the raw matter, asking it to perceive itself in a different way. As Sylphrena rather gently explains to Kaladin, who at first blush is a naïve scientific realist, the gravity he manipulates when he climbs up walls isn’t so much a “law,” exactly, but “more like an agreement among friends” (130). Focusing only on the metaphysics of the book, however, risks understating the complexity of its political dimensions. One of the striking features of fantasy fiction since Tolkien—especially in contrast to science fiction—is how rarely authors depict democracies. Given absolute freedom in imagining alternative worlds, the political systems they select are almost invariably variations on feudal monarchies. In some authors, this is probably an accidental feature of the semi-historical setting. Sanderson, however, has made it an issue of thematic concern. In the Mistborn trilogy, the series of fantasy novels he completed before The Stormlight Archive, the anti-democratic ethos is in fact shockingly blunt: the hero of the series has a crucial epiphany where he realizes the naïveté of his democratic ethos and subsequently declares himself an emperor. The Way of Kings started The Stormlight Archive down a similar path: at the end of that novel, Dalinar realized that he could not persuade others to follow his ethical ideals and that he had to impose them through his position as Highprince of War. Words of Radiance extends this suspicion of democratic reform via Kaladin’s narrative arc, and particularly through his moral dilemmas as Elhokar’s bodyguard. In bonding with his spren Sylphrena and acquiring his magical abilities, Kaladin committed himself to what the book’s theology calls “The Second Ideal of the Knights Radiant.” He vowed, in dramatic fashion, “to protect those who cannot protect themselves.” Sanderson shows how a dilemma can grow from even this seemingly simple injunction: what if those we have to protect are politically disastrous? Don’t a king’s bodyguards, Kaladin asks himself, have a duty to protect the victims of a king as well as the king himself? Might not one ultimately protect more people by letting assassins kill a bad king? The way the novel ultimately represents this dilemma, however, and the possibilities for its solution which go ignored, are significant: Sanderson manipulates the reader’s sympathies so that the reader cannot help but agree that the political system should be maintained. There is thus a way in which the novel participates in what Friedrich Nietzsche would call slave morality: “protecting those who cannot protect themselves” ends up, oddly, leading to Kaladin’s decision to serve an oppressive political regime. The process by which the novel makes this reasoning appear adequate, both to Kaladin and to us, involves both a certain narrative sleight-of-hand and several distinct assumptions about political life. Crucially, Kaladin is a nascent political revolutionary. As a man with dark eyes, he is a member of the lower caste, and he is occasionally suspicious that Alethi morality is simply part of the social system that oppresses “darkeyes” for the benefit of the “lighteyed” nobility. Events seem to prove this to him when he saves the lives of Dalinar’s sons by entering a duel at great personal risk, only to find himself imprisoned when Dalinar’s plot goes awry. Visiting him in prison, Dalinar tells Kaladin that he must manfully bear the suffering. As he puts it, Kaladin won’t change the perception of darkeyes by “screaming like a lunatic”; rather, he must “be the kind of man that others admire,” stoically suffering and caring only about his duty (750). Kaladin, regarding this advice with a healthy skepticism, suspects that Dalinar is advocating slave morality: as he puts it to himself, Dalinar’s advice ultimately boils down to the injunction to “Stay calm,” “Do as you’re told,” and “Stay in your cage” (751). Moreover, as he realizes, Elhokar really is a terrible king who deserves to be replaced. Formally, however, the novel dismisses such political concerns and commits itself to the validity of ethical commitments. At the last possible moment, Kaladin concludes that he cannot allow Elhokar to be murdered, and the novel endorses this decision in numerous ways. While contemplating participating in the assassination plot, Kaladin lost his magical abilities and in fact deprived Sylphrena of consciousness, but both Sylphrena’s awareness and his abilities return when he re-utters his oath. What he concluded, he explains—dramatically standing over Elhokar’s wounded and bleeding body with only his pocket-knife—is that he cannot protect only the people he likes, since that would he mean he doesn’t care about “doing what is right”: “if he did that, he only cared about what was convenient for himself.” Tellingly slipping into free indirect discourse, merging his voice with the narrator’s, he thinks, “That wasn’t protecting. That was selfishness.” That this justification is inadequate should be obvious: the only thing it demonstrates is that personal preference alone does not offer a substantive criterion for moral deliberation. Crucially, Kaladin hasn’t offered any answer to the hard political question, namely, whether Elhokar should stay in his position as the Alethi monarch. He has just concluded that his decisions about whom to protect should be based on something other than personal affection. The novel, however, hides its lack of an answer by eliminating the other options that would demonstrate the importance of the question: it is only when the sole form of resistance to the regime is murder that Kaladin’s ethical qualms can offer sufficient reason for the political act of supporting the king. The notion that there might be non-murderous or even peaceful forms of protesting Elhokar’s rule or the system of Alethi segregation goes unrecognized. In this way, Words of Radiance demonstrates a fundamentally conservative mindset. One of the main precepts of Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, one of the intellectual bedrocks of modern conservative thinking, is the notion that citizens ought to resist attempts at political revision based on reflective analysis of the state, even if that analysis seemed correct. As Burke puts it, the “stock” of “reason” in “each man is small,” and “individuals would do better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations and of ages.” He explains further that wise men do not seek to overcome “general prejudices” but rather “employ their sagacity to discover the latent wisdom which prevails in them.” The point here is that we ought to know and recognize our limitations: even if a given change, like the overthrow of a king, seems obviously correct, wise citizens know that the traditions and “prejudices” of the state are in some ways wiser than they are, and thus suspect their own rational conclusions. In this sense, Kaladin is properly humble, falling back on his ethical principles—even while suspecting that they might be social prejudices—instead of seeking dramatic political change. One of the most fascinating interludes in Words of Radiance resonates with this line of thought. Elsewhere in Roshar, there is a city-state called Kharbranth, whose king Taravangian experiences wild divergences in intelligence: some days, he wakes up a genius, while on others he lacks even basic intelligence. Cleverly, he’s designed a series of measures to control his condition; for instance, he assigns his caretakers to give him a test at the beginning of each day to determine how intelligent he is, and he has laid down certain procedures for what he can and cannot do on a given day given his intelligence. “When he was dull, he could not change policy,” the narrator explains. Additionally and interestingly: “He had decided that when he was too brilliant, he was also not allowed to change policy.” This way of thinking about politics and intelligence reflects a deep sympathy with Burkean conservatism, insofar as it demonstrates a worry about people who believe themselves intelligent enough to have solved a problem, but who are in fact incapable of grasping the true dimensions of a situation. As Taravangian is on his mediocre days, ideal politicians are humble enough to recognize the limits of their own capacities: they don’t believe themselves smart enough to grasp all the complexities of life a set of prejudices represents, even if it seems possible to improve on some aspects of the state. In Sanderson’s telling, the complexities that one cannot explain or address, but which must simply humble the efforts of reforming characters, seem to follow from the fragility of the state. Citizens should not overthrow kings, the novel implies at a number of moments, because if they do civil society will dissolve. In particular, the tension in Alethkar is set alongside a civil war in a country called Jah Keved, whose king was assassinated in The Way of Kings; by the Words of Radiance, the ensuing civil war has virtually “depopulated a kingdom” (905). Concurrently, when Dalinar protests that the state ought to be strong enough to survive the loss of one man, his son speaks for the ethos of the novel when he says, “Well, it’s not there yet” (592). Again, this resonates with a Burkean idea. Looking at the French Revolution, Burke concluded that one could not regard the state simply as a contract between its citizens, which could be “overturned” at will, but must be “be looked on with other reverence.” A state based on the will of its citizens, like a genuine democracy, would always be liable to dissolution. Thus the real reason motivating the novel’s judgment that Kaladin’s decision to support Elhokar’s monarchy was morally correct is the fact that Alethi society will dissolve without the governing hand of a legitimate king. Of course, since Words of Radiance is a work of fantasy, it may very well be “true” that “society” would so dissolve. But it is worth keeping in mind that oppressive regimes throughout history have justified their reign by insisting that the stability of the state requires their continued rule. Now, two important caveats are necessary. First, Sanderson does not romanticize Alethi society. The novel is under no illusions about the oppressive nature of the regime it describes: if it is worth defending, it is so not because the current regime is ideal, but because the alternative would be so much worse. In addition, this is of course only the second book in what will be a long series: we do not know where Elhokar is headed as a character, and all of these ideas may look very different by the end of The Stormlight Archive. The thematic continuity with the Mistborn trilogy, however, suggests that the conservative and anti-democratic ethos of the series is likely to persevere. While chatting with me about this review, a friend observed that—in keeping with the Nietzschean overtones of the novel—Sanderson seems fascinated by worlds in which God is not merely dead, but has died recently. The Way of Kings, in fact, concluded with a vision where God—speaking from beyond the grave—literally tells Dalinar that he is dead, and that “Odium” has killed him. In a brilliant but dark plot twist, Words of Radiance reveals that all that remains is the spren of God: not an independent entity at all, but a being constituted precisely by the hopes—now fading—that there must be a God somewhere. It is ultimately the confrontation with the death of God, I suspect, that motivates the fundamentally bleak politics of the novel. |

Patrick Fessenbecker is a professor in the Program for Cultures, Civilizations, and Ideas at Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey. He completed his Ph.D. in English at Johns Hopkins University in 2014, and is currently working on “Novels and Ideas,” a book manuscript based on his dissertation. His essays have appeared in New Literary History, Nineteenth-Century Literature, and Studies in English Literature, and he has written reviews for Review 19, Modern Language Notes, and The Journal of Literary Theory.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig