by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Anchor Books, 2011 | 336 pages

In the last mass extinction the Earth had seen, an asteroid collision blanketed the Earth in darkness and toxic fumes. First to fall were the prehistoric behemoths, their armor plating and fanged arsenals unexpectedly ineffectual against the suffocating darkness. Those that survived were not the apex predators – not the titanic dinosaurs nor the well-adapted pterosaurs – but instead the small and the meek, the scurriers and the burrowers. It was they who outlasted and outlived.

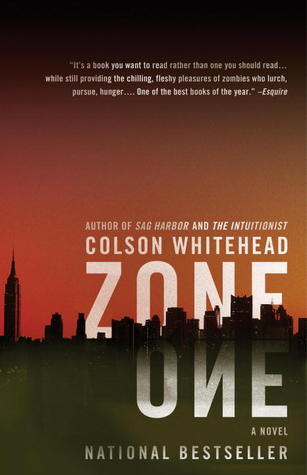

Colson Whitehead’s Zone One imagines a subsequent descent of darkness upon the world, this time that of a zombie plague that nearly extinguishes the global population. Like those who once found an Earth littered with the bodies of their reptilian brethren, Zone One’s survivors emerge from their bunkers to find toppled ruins haunted by “stragglers.” These are not, however, your run-of-the-mill zombies, but rather, inanimate tableaus of their former selves, frozen into upright comas. Unlike “skels,” their ravenous, ghoulish kin that were quickly hunted down and eliminated early into the outbreak, stragglers are as harmless as they are pathetic – locked in the interminable banality of riding in a bus without wheels or standing next to a copy machine long since broken.

In this way and others Colson Whitehead’s novel upends the traditional zombie tale. Its story spans three days, interrupted sporadically by fragmented flashback sequences to various, seemingly unrelated, characters and scenes. There is, in other words, no extended characterization, no deliberation of action, and sparse exposition of plot or events. For one, we never do find out what causes the plague. Whereas prototypical zombie plague survivors brandish high-powered weaponry in a glory-bound quest for headshots, Zone One’s survivors do not face the imminent threat of death, but rather the tedious business of existence. There is neither danger nor acclaim in bagging a straggler. Only paperwork.

The hub of the reconstruction process, is, of all places, Buffalo, whose retrenched bureaucracy trivializes past horrors and loss while dubbing their ragged enclaves with names like “Happy Acres” or “Babbling Brooks” that belie the camps’ grim encasement of barbed wire and manned turrets (to repel the occasional skel). The majority of Zone One’s action, however, takes place in downtown Manhattan, where Buffalo has sent in teams of citizen-turned-warriors to comb through the ruins and eliminate the remaining stragglers.

In one of these teams we find the novel’s protagonist, Mark Spitz (never just Mark), who possesses neither heroic strength nor exceptional cunning, but a persistent aptitude for the mundane. Sheer ordinariness turns out to be his salvation; being exactly in the middle of the pack delivers him from the rashness of the audacious and the ill-timing of the belated. A self-described “B” student in school and indeed very much throughout life, Mark Spitz finds the transition between pre- and post-apocalypse surprisingly smooth, his past life as an office lackey seamlessly segueing into his new role in his “sweeper unit.” He has, as he admits, a penchant for following orders.

Despite the ease of actually killing the stragglers, the bureaucratic process that killing entails turns out to be no cakewalk. In addition to filing incident reports, Buffalo demands that Mark Spitz log demographic data, including the ages of the undead and the number of the floor on which they were found. In a world literally covered in undead, where every corner, alley or buildings stages an “incident,” filing these reports is a descent into the inane. Zone One is, to this extent, an Orwellian dystopia of an all-reaching government fixated on bureaucratic control.

Whitehead’s is a subtle allegory that suggests, in a very real sense, not much has changed since before the plague. The humdrum of suburban life, the predictability of career paths, the rows of office cubicles, the preponderance of “judiciously apportioned 401(k)s”… all persist in the post-apocalyptic world of Zone One. While the survivors are beset by establishment monotony, it is also inscribed literally onto the bodies of the nameless undead, who, like the yuppies produced by professional uniformity and the culture industry, are mindless consumers – this time of flesh, not products. The concrete and barbed wire barrier that separates the survivors from the undead is in fact nearly the only thing that separates them – everyone in Zone One, whether a capitalist drone or the living dead, seems submerged in the same ennui.

Not Mark Spitz, however. Long before the plague, Mark Spitz seems to have intuited, without conscious analysis, the world’s profound indifference. If there is a “heroic” element to his character, it is here, in the depth of his intuition of the changed nature of the world, as well as in the maturity of his acceptance of it. He does not, for example, become suicidal, nor is he possessed by Hamlet’s sense of existential inaction. Instead, like Melville’s Bartleby, he registers it, and simply persists.

Structurally we are led to pin our hopes on him: he is our protagonist, our survivor, and the vehicle by which we navigate the post-apocalyptic landscape. And we do, though he refutes exemplarity and exceptionalism at every turn. His secret? Living in a keyhole temporality of the present moment, never thinking of the past or future. It is tempting to imagine Mark Spitz bobbing like a cork in Zone One’s sea of undead, ebbing and flowing, enduring without trying. Things seem to just happen to Mark Spitz, regardless of his intention. For his part, Mark Spitz refuses center stage and attempts to recede into the ordinary by averring repeatedly that he “was their typical, he was their most, he was their average.” The reader closes the novel with no knowledge about him as an individual – not even a real name.

Mark Spitz’s steady refusal of generic responsibilities could have made him a misanthropic protagonist – difficult to relate to and difficult to follow. However, from a broader perspective of literary innovation, Colson Whitehead’s anti-characterization of Mark Spitz introduces a masterful critique of the rhetoric of heroic exceptionalism undergirding the zombie survival genre by reminding us of the crushing existential despair of the post-apocalyptic world (and perhaps in ways our own as well). The OED defines an apocalypse as “irreversible damage to human society” – essentially, an event that no one survives. Zone One resurrects the tautology inherent in the phrase “apocalypse survivor” by examining the paradoxical state of this survival – not as glamorized rusticity or as militaristic fantasy, but as the agonizing continuation of the quotidian, where the mechanization of life finds unfaltering convergence with mechanization in death.

In the end, Colson Whitehead’s novel is a subtle, cerebral, and engaging work that considers the posthuman, not in terms of the liberative potential of Donna Haraway’s cyborg, but as what UC Davis English Professor Sarah Juliet Lauro has also identified in the figure of the impassive zombie. Individuals do not survive, but systems do. Zone One suggests, through an unrelenting but fitting strain of dark humor, that the individual under capitalism has always been undead.

Allen Zhang is an English PhD candidate at UCLA. His research is primarily focused on monsters in nineteenth- and twentieth-century literature. He was the recipient of the Arthur Feinstein award for his work on Chicana poet Gloria Anzaldúa at Dartmouth College, where he received his BA in English.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig