by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Knopf, 2010 | 320 pages

Tom McCarthy’s debut Remainder (2005) was an original contribution to a fascinating novelistic tradition—let’s call it the allegory of control—in which all the formal resources of narrative voice are marshaled in the representation of some anti-hero’s obsessive attempts to manage his environment. John Fowles’s The Collector is a classic instance of the genre in its tragic mode; we might think of Beckett’s Molloy, with its eponymous hero’s compulsive stone-counting, as an example of its comic. Remainder is narrated by a trauma victim who, after being awarded eight-and-a-half million pounds in a settlement, spends his money attempting to re-create, down to the last detail, events that have already happened. When, for example, a neighborhood drug-dealer is gunned down in a gang t urf-war, our narrator arranges for a 24/7 re-enactment of the shooting, to be performed whether he’s watching or not. The thoroughness and spooky precision with which McCarthy depicts this narrator’s obsessions made the short Remainder an effective and highly unsettling read.

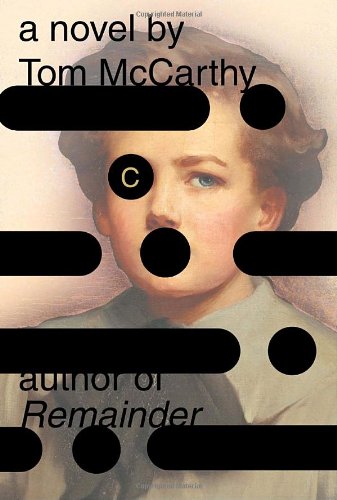

McCarthy - a conceptual artist and author of Tintin and the Secret of Literature, a post-structuralist study of Georges Remi's Tintin comics - followed up Remainder with a very different kind of novel. C is an historical Bildungsroman, set in the first thirty years or so of the twentieth century. It follows the life of one Serge Carrafax, the son of an eccentric Englishman who runs a school for the deaf and experiments with early communications technology. Serge’s childhood is marked above all by the presence of his precocious and eventually suicidal sister Sophie, who spends her adolescence performing brilliant amateur chemistry experiments. When the Great War breaks out, Serge becomes a fighter pilot; after the war, he takes loads of drugs and joins the London demimonde, eventually gets clean, and assists a British colonial team in Egypt scouting for radio-tower locations.

Networks—technological, linguistic, symbolic—are scattered profligately across C, hinting at but refusing to disclose a grander unifying structure. Our necessarily partial comprehension of the systems that structure C’s modern lifeworld gives rise to a very recognizable brand of literary paranoia. The letter “c” reappears with a persistent regularity meant, perhaps, to be eerie, though the effect is rather comical than sinister. This is a Big Postmodern Novel About Systems—C, after all, rhymes with Pynchon’s V.—and its principal virtue may lie in how clearly it delineates the generic calcification of the type of fiction the scholar Mark McGurl has referred to as “techno-modernism.” Pynchon remains the living master of this particular postmodern idiom, with Delillo its important minor practitioner.There’s something disappointingly derivative about McCarthy’s version of the network-novel; often, C reads like a collegiate parody of Underworld. Consider, for example, this unfortunate description of Serge passing wind: “He lets a fart slip from his buttocks, and waits for its vapour to reach his nostrils: it, too, carries signals, odour-messages from distant, unseen bowels.”

It’s entirely possible that this is meant to be funny. C abounds in semi-parodic allusions: to The Magic Mountain, Stan Brahkage’s film Mothlight, Renoir’s The Grand Illusion, Freudian and Derridean theory, the literary experiments of Raymond Roussel, and doubtless many more I’ve missed. But C is less than the sum of its allusive parts; it fails sufficiently to stake out a fictional idiom of its own.

This failure has to do, I think, with a pervasive sloppiness of style that—at least for this reader—was difficult to get beyond. The sections of the novel dealing with Serge’s childhood often achieve an inspired weirdness, and McCarthy has real gifts as a stylist, though even in its best moments C can seem, at a sentence-by-sentence level, to have been dashed off a bit quickly. Here, for instance, is Serge’s discovery of Sophie’s self-poisoning: “It’s only as Serge turns away that he registers, like an after-impression, the flecks of brine that cover Sophie’s lips like bubbles blown by a departed insect.” Those bubbles are great—sinister and sickening, and sad too—but why the double “like”? Like an after-impression, like bubbles blown….the repetition is awkward, and the simile, anyway, imprecise—surely this delayed registration is an “after-impression,” not merely like one. This may seem like quibbling, but one feels that McCarthy, in spite of his better self, generates sentences in C whose syntactic awkwardness approaches unreadability. Here’s one: “The lower section of this board’s become so crowded that it’s half-occluded: the morning’s light vapour blanket’s thickened to an opaque shawl.” Why in the world are these nested possessives necessary? The sentence annoys, exasperates. Similar lines are, unfortunately, by no means unusual in this novel, and can actually induce headache. I, for one, badly miss the near-Beckettian minimalism of Remainder.

Len Gutkin lives in New Haven, CT, where he is studying for his PhD at Yale.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig