Today I am in the Illinois Department of Human Services building in Chicago’s South Loop. It looks like an old Mosque. On the left wall, there is an enormous mosaic panel of two coconut trees growing out of sand. There is a sea of us—rows of black plastic chairs filled with people, mostly black, in heavy winter coats, mostly black. I am white.

I take a number, a piece of paper with a number written on it in black marker: 9. We are not on time. They don’t take appointments. Not in any way that you might conceive of “appointments.” Sometimes, if you happen to get a hold of someone on the phone, they might send you something in the mail, saying you have an appointment at ten. Then you walk in at ten and you take a number and wait, just like anyone else who happens to walk in the door at ten.

I am here because I lost my job and haven’t been able to work. My brain lets me type things for brief times. And because I have been writing my entire life, I can write, but it is not like “writing-writing.” It is like playing music by ear. It is like speaking to ghosts in a trance state.

People might say, “But you write such a coherent/cohesive email.”

But I can play music by ear. I can hold it together, words of this and that, for a moment or a minute, especially if I am writing friends or friends of friends. We make shortcuts and talk poetry style. I don’t even announce myself properly. I just type, Elisa, what’s the word for x. And how’s John. And you of course. Shoot—yeah, I loop backward. You first, John next, but still, or maybe, whatever, she forgives me, she gets intention. Everybody’s important. The question is important.

I am here with my husband. He goes everywhere with me, like my bigger, slower shadow. He wants to be sure I don’t fall into a state where I start crying or clanging.

***

There is a name for what I do lately: clang. See? Name/clang/lately/dang. It’s called the “clang association” in medicalese. Doctors/namers think of everything.

In some states of schizophrenia or mania, you get stuck—you hear sounds, symbols, rhythms, you start rhyming. If you are especially word-oriented, you might start rapping. I am and have and do.

I see a design that is especially beautiful and functional, like shoes that look like legwarmers and sneakers and flip-flops at the same time. And I say to the tall black girl in the elevator at Whole Foods, “Look at your shoes! Oh my god! Good for you!” Shoes/you/you/shoes/Whole Foods, and she laughs, saying “Thank you!” with such joy and pride that I know she means it.

I see a five-year-old child so self-confident, she makes it look so easy, my eyes burn with tears and admiration. She holds the cell phone to her ear and says, “Okay Daddy, Okay Daddy, Okay. Okay Daddy.” Clip. Snap! Snaps the phone shut, does a head swivel to her grandma, like, done, so easy, and I turn to the grandma, in tears, and say, “She’s so cute, she owns the whole phone company, no?”

I add the “no” because I think she speaks Spanish, but also because it goes better with whooooole and phooooone. I drop the s, I repeat it, and drag it out. “She own the wholeeeee phoooooone company.”

The grandmother laughs, and her own eyes are glistening at the privilege of holding this child in her arms. We bond. It is the Salvation Army and we are walking through the aisles of clothes, color coded—brown, grey, black, light brown. Is there a color of clothes that rhymes with Moses?

You would think people would be mean to the mentally ill—there are stories—but in this political climate, they find me a relief. They shower me with like-minded sentiment. They know I mean well, and they will take it in whatever form.

***

To come to this appointment at the Illinois Department of Human Services, I had to first gather medical notes from past hospitalizations, two in the past four months. The notes itself are a form of poetry.

Patient claims she has painted herself white.

Patient insists that she is all knowing of light, time, and space.

I am just a normal person, really. I have twin daughters and a husband. My husband is a painter, a real one, but for the past thirteen years, he has been mostly a caretaker. I have been mostly a moneymaker. Maker/taker/baker. I forgot: my daughter Laith—faith, waif—she compulsively bakes. I forgot to tell you that, and she’s very good with cakes/bakes/cakes. Rhymes allow us to remember and consume the things that would have been otherwise uncovered unbaked unmade.

See, my other daughter Issa is disabled. These are fake names. They are the names I would have named my twins if they were boys. They almost died, but they lived. I almost died sometimes, and I lived, too. And now I am disabled, and I have come to this very room to prove it. To bring in my tome of disordered thinking, and say to the social service worker: I am messed up, and in two weeks, I will be homeless. We will stay at my friends Chuck and Angie’s or we will stay with my father-in-law, or we will stay with my parents, or we will stay on the floor in my husband’s studio. We don’t want to think about the other options.

My father says to me, “How do you see this story ending?”

It clangs, the storeeeey and the endiiiiiiing.

I say, “Do you mean like with a whole cast of characters and everything? Do you mean like in chronological order or what? Like a hero’s journey? I mean, I’m not sure what you mean, Dad, how detailed you want me to get.”

He says, “I just mean, how do you see this playing out?”

I am so relieved to be relieved of the detail of story, I almost sigh.

I say, “Oh, I think in the end, everybody is really nice. I am optimistic. I think it will be great.”

My dad looks unsatisfied by the brevity of my story and perhaps the slant of it. But at least I did my best. I am a poet, and I try to keep things short and understandable, although it doesn’t always work out that way.

***

I am still waiting. When you come at ten to the Illinois Department of Human Services, you will wait until they call your number. Once they call it, that doesn’t mean they will see you. It means that your name gets put into another queue, and if they don’t run out of time, they will see you by the end of the day. Of course, they don’t see anybody from twelve to one—that’s lunch—and if you wait in the queue until longer than two in the afternoon, they send you home because there’s no chance you’ll be seen that day. It’s tricky. It’s the government. You can put up mosaic coconut trees but there’s no hiding it.

The woman we finally see is named Sara, like my sister but without the h. She has taken the S.W.E.A.T. Pledge—Skill and Work Ethic Aren’t Taboo. She has proof—a sign on the wall of her office. Among the many tenets of the Sweat Pledge is the first: I believe that I have won the greatest lottery of all time. I am alive. I walk the Earth. I live in America. Above all things, I am grateful.

The second tenet (which I can now type because she is taking my tome and making copies of it at the copy machine) is this: I believe that I am entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Nothing more. I also understand that “happiness” and the “pursuit of happiness” are not the same thing.

Taped to her wall Sara has a printout, a picture of a boy, probably five years old, who I assume is her son. He is squeezing his cheeks together like he has just eaten a lemon. On the side of her metal desk are pink plastic letters—a message, arranged (I assume) by her assumed son: IUWOM. I laugh. This is how language feels to me. It makes sense when it shouldn’t and doesn’t make sense when it should. Either way, it gets felt in waves and words and rhythms and color.

What would happen if we were all like Sara. She remembers us from last time. I have put all my hopes into Sara because she must love her son, which means she might have a feeling almost like love toward me because I have daughters and one is severely disabled—autistic, cerebral palsy, hydrocephalus, a corresponding VP shunt, optical nerve atrophy, gaze apraxia, and periventricular leukomalacia, a form of white-matter brain injury.

I feel almost normal around her (both my daughter and Sara). Then I start to worry. What if Sara thinks I’m too normal?

***

At the doctor’s office yesterday, I worried about the same thing. I needed Dr. Segar to fill out forms for my application for disability. I watched her check the boxes describing my mental function—mild, moderate, mild, moderate, moderate. I almost cried. The insufficiency of mild, the checkbox. Why don’t they have a picture of fried eggs that you can check?

I said, “I have trouble, you know, delusions, I have grandiose thoughts.”

She said, “Like what?”

I hesitated. “Like if I wanted, I could talk to movie stars. Ugh.”

She laughed, “At least you have insight.”

I said, “That’s the worst thing I have. I wish I was completely blind.”

I realized, as soon as I said it, that it was not true. I realized that for me, not knowing is worse than knowing because not knowing strikes fear in me that is impossible to render on the page.

I said, “You probably don’t know this…”

The doctor continued to fill out the paperwork.

I stopped and started again, trying to sound more accurate and less condescending. I said, “You probably know this because you are a doctor. But do you know that during manic stages, you have no idea what you say?” I meant “me,” but I left it in second person because I have read research that says that people understand and retain information 80 percent better if told in second person.

I said, “Like it is completely unavailable to you, whatever you say or do within that window of time?”

I wanted to communicate my fear, but it did not render with the proper amount of emotion in the air.

She nodded, and said, “Hmm, yes,” and the nod and the yes should have felt satisfying but it felt like everything feels now—far away and not enough to communicate the intensity I desire to feel in my head, my bones. It felt like a mild checkbox instead of a plate of hot fried eggs in my face.

When she left the room, I cried. To myself, to my jury of invisible and doubting peers, I said, Listen, you don’t understand. This is not laziness. I love working. The year before last I made 125 thousand dollars as a writer and designer. But now I am crazy and I can’t put two sentences together. I swear to God, I don’t even care how normal I sound. I can’t. I think people are coming after me, and I don’t know why kids have to carry dolls around with them. They have legs that dangle and they freak me out. Why do they all do that?

***

Sara comes back from copying all my medical forms and records. I was hesitant to even give them to Sara, they seemed so heavy and mostly unnecessary, but she convinced me because she said, “Listen, people come in with entire boxes.”

She sings into the air, “Sorry, Trees!” and hands my paperwork, heavy and mostly unnecessary, back to me.

She tells us we did a great job with the paperwork. We are approved.

We cannot believe it. It is hard and hard and hard, and impossible, and 400 pages and hours later, someone like Sara just walks in and says, “Great job. Approved. Check your card tomorrow. The money will show up. $465 a month, family of four, the maximum.”

Emergency financial assistance: received.

We thank Sara. We thank her again. I rush out of Sara’s office before I start to weep.

A little girl runs past me. She is so determined and so self-confident, like the Salvation Army girl on the phone with her daddy. She burns up the carpet like she is running the race of her life that she knows she will win. She can feel victory all the way up to her hot flashing eyes.

My husband laughs and says, “She got right past that security guard, didn’t she?”

I nod because I cannot speak. I am crying. I am so thankful for Sara and for children. I am so thankful for grandmas and fashion plates who laugh with me when I am rapping about their clothes and their grandkids and their life and mine.

I feel the Sweat Pledge in my body. I stand up straighter with the recognition that I too will live again. It may take some time.

I believe that I have won the greatest lottery of all time. I am alive. I walk the Earth. I live in America. Above all things, I am grateful.

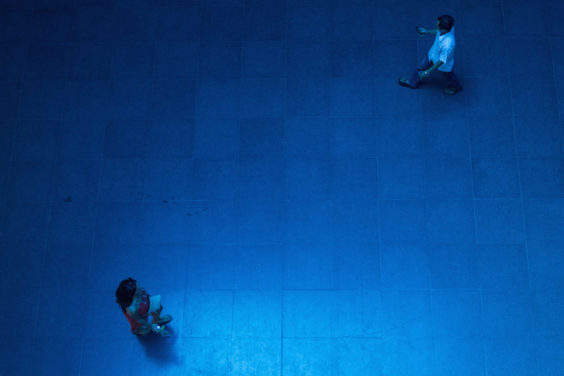

Image courtesy of Harrison Henry Martin.

Liz Hildreth is a writer and poet who lives in northwest Indiana.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig