by Dustin M. Hoffman

“And what’s the confession?” McLean asked, changing the subject and putting his tumbler on the black metal table.

Winkowski raised his bushy graying eyebrows as though it was already apparent. “That I think she’s an idiot and I don’t fucking care.”

McLean was hoping for something juicier, an affair or cross-dressing or at least tax evasion. The daughter thing wasn’t anything new after listening to an entire meal of complaints dished out in his friend’s businessman voice: Winkowski’s wife blamed him for “screwing this girl up by not hugging her liberally enough,” “the queen,” Winkowski’s pejorative for his daughter’s gay therapist, said the girl was “an ‘ideal candidate’ for a nervous goddam breakdown,” and if she has one she’ll never be the same—but if she makes it through her early twenties without one, “he says her brain chemistry changes and everything should be fine.”

McLean’s own confession, he thought, stubbing his cigarette out in the ashtray and pulling a fresh one from the pack, regarded being too old to happily masturbate in a studio apartment with no hot water. Just a glee-free tool to fashion sleep.

“Look,” Winkowski leaned his elbows on the table and brought the conversation back to its crux. “When I’m faced with a decision like this in the office, I powwow with my lawyer about worst-case scenarios. The worst-case scenario for us right here is she gets expelled. Which’ll happen anyway. And your academic name gets smeared. Which it already is. This is an arbitrage opportunity for you.”

It wasn’t the first time Winkowski offered him money on this patio. The last time wasn’t for any task, just a gift to offset the costs of losing house, job and family. McLean had been too prideful to accept it. Now his old friend was back to ask a favor—the Italian suit begging the aging juice-stained blue jeans and pseudo-seventies tawdry tawny tee-shirt with The Dragon Diner scrawled across the chest above a smiling white serpent (short sleeves giving way to graying arm hair) for the one thing that couldn’t be safely bought from anyone else. It was hard to play too dignified to take it—to let his ethical vanity stop him from helping both of them—after he hadn’t been dignified enough to forsake the cliché of risking his wife and livelihood to pop his poignant, pungent peeper six and a quarter lovely lonely inches into a starry-eyed undergrad.

Winkowski raised his hand and snapped at the pretty Asian waitress, to ask for the check. McLean hated when his tables snapped at him.

He politely declined the ride home, mentioning he liked the chilly November air, and walked thirty-nine blocks on the sore ankles of a middle-aged waiter. His thoughts fell to the dysfunctional etymological family of humus. Latin for “earth,” ancestor of humilis (“low”), and the sculpting medium of those complicated prideful “humans.” But when you’ve been inhumane and inhumed your pecker in the wrong humid humidor, falling low in social standing from an assistant professor and published author to an unemployed pariah, you are humiliated, cultivating your humility, leaving you grounded. It liberates you to do things like live in your car until you find an apartment after your wife kicks you out, frees you to take jobs like waiting tables in a chintzy diner at forty-three years old. The irony emerges: humility immunizes against humiliation. Monasteries were right to advocate it—truly humble people, not as economical or social euphemisms for impoverished but simply humble, are the freest on earth. Free to climb to the zeniths of Gehennam. Free to take money for plagiarizing.

It wasn’t really so different, he thought climbing three flights of worn gray carpet and fishing in the stagnant hallway for keys to the worn teal door with the silver plastic adhesive numbers 1066, than ghostwriting for a celebrity.

§

He pressed the control button and the e key, sending the curser to the center of the page, and typed:

DELICIOUS SUPERSTITION

By

He reached for his pack, the little logo of a silhouetted Indian Chief smoking a peace pipe, and typed:

Lori Winkowski

“So,” he said aloud to himself, lighting the cigarette, “this is happening.”

The angels were inherently, the keys pattered softly under his fingers, invisible. They came, ordered—concise and organized—then ate as he jotted copious notes, shorthand modifiers of that and substitutions for this, for the humans—invisibly as he apologized (in English to the picky, generally condescending customer, then Spanish to the kitchen) if he missed a detail, invisibly as he practiced that obsequy of optimism, obsequiousness, to spoiled children of all ages on family dinners and dates and business lunches—and then, barely noticed, were gone with a 25% tip on the table.

Two proofreads of the paragraph later he stubbed out his cigarette and lit another, smoke scraping down his raw throat.

To even glimpse the angels eating, he learned, you first have to understand the subspecies of “Please”. The first, the easiest to recognize, is the Horrible Please—it’s easier to see evil Pleases than decent ones. He learned to recognize the Perfunctory Pleases tacked onto the ends of demands. He learned the Impatient Please. Then came The Substitution For “Yes” Please. When you can identify please species like a shirpa, you can, by elimination, begin glimpsing angels.

He stopped, glanced at the paragraph and, remembering a plant he’d wanted to use, wrote in brackets and capitals: [WORK IN MOTIF OF TERMITES EATING OUR BUILDINGS TO CREATE THEIR OWN, PEOPLE DO THIS ALSO WITH MOUTHS …HAVE THE DINER BEAMS BE INFESTED WITH TERMITES…PLAY ON THE WORD TENERAL.]

He wondered what species of please Layla would use if she came in, if he took her order, standing attentive at her table. And she’d have no clue in her child’s mind, ordering that stupid food.

She wouldn’t notice him if they met for the first time now. All the glances he ignored as a relatively dark haired professor from the baccalaureate neophytes of adult life dissipated when he started serving the same demographic as a graying waiter. Back then they’d loved him more that he was a critically scorned elitist. Now they seemed to smell his sore feet, the child support he paid for the kids he wasn’t allowed to see. The students’ attraction wasn’t to him but to things he’d possessed: job, family—things they didn’t want to keep but simply to destroy in self-affirmational play like kittens practicing hunting skills on tortured grasshoppers or middle school lovers wistfully dismembering horticultural sex organs futilely asking if “he loves me not.”

As a professor, he had loved Layla not, but she won anyhow. He’d laughed with the rest of the class when she half-jokingly declared herself an Übermench, but now wondered if she was simply one of another sort.

Layla…

The rough draft was six thousand words that he whittled down over a week to the necessary three. He swayed gently in his chair on his last rewrite of the second half of the last sentence…

…that Neitzche, Gandhi, Christ, anyone who grappled with and controlled the Self in any capacity faces the paradox that it is the very arrogance of the Self that drives any self-improvement based battle against it—that we are purified not from but by our sins—and that the famous conscious transducers of their own energy were so spiritually teneral, so un-Übermench, that they fell into philosophical incarnations of adolescent megalomania, not realizing an addiction to the selfless Self is the basest of addictions and the base of all others—Christ wasn’t a termite worker with great plastering saliva, McLean drew hard on the butt of his cigarette, it crumpled from the heat, softening in his lips, he’s a soldier with mandibles so unwieldy he must be fed by others’ devotion to survive, who committed autothysis for the mud, for the mortar and brick, for the steel and glass of the termitaria.

He stubbed it out, leaned back in the rocking chair at his desk, and lit a new one luxuriously. The story was a perfect undergrad assignment—filled with emotional gravitas and misguided assumptions of original intellectual discoveries. As the smoke issued in his breath he imagined himself a vicious dragon with a stolen maiden in stash and scutes the garish red of his first girlfriend’s lipstick.

§

“What?” he wiped his face with his free hand, sitting down on his daybed.

“C minus,” Winkowski’s voice fought across the line against the airport cacophony behind it.

He reached for the blue pack. “What did he write?”

“‘Lacks plot, structure, and meaningful conflict. Bogged down in poetry and philosophy.’”

McLean nodded, looking down at his mismatched socks. “How is Communism and Christianity,” he lit up, “incestuously copulating in…in violent passion…to bear a hedonistic, nihilistic, ethical egoism influenced incarnation of Liberation Theology…no plot and no conflict?”

“Well Brian,” Winkowski’s aggressive sigh was audible over the airport din, “I guess he just didn’t get that out of a story about a waiter not liking his tables.”

“Well then he’s a fucking idiot who shouldn’t be teaching, and I—”

“I’m sure he’s an idiot with no business…breathing…but I ran the numbers and she needs this last grade to be at least an A- to get a D in the class.”

After an apologetic silence, McLean said, “That teacher’s a fucking asshole.”

“I need her to pass this class,” Winkowski replied more calmly. “Brian, I love you like a brother, but this is why you are cynical and I am not. Because I don’t care if he’s an asshole or understands literature. He’s nothing to me. He’s some stupid loser who doesn’t know his ass from his elbow and we need to figure out what he wants to hear and we need to tell it to him to—” the reception was lost for a second, “—and manipulate him into letting us steal this grade from him. Telling people what they want to hear to get them to do what you want isn’t belittling yourself or respecting them. It’s a real-world Jedi mind trick and the most belittling thing you can do to them.”

“By letting this asshole control my writing.”

“It’s Lori’s writing,” Winkowski said. “And yes.”

§

ALMOST HUMAN

By

Lori Winkowski

Leaning back in his rocking chair, McLean decided “meaningful conflict,” meant “obvious conflict,” and decided to write as a cuckold—opening the story as a letter to a debauched wife who’s left the protagonist for a younger more successful wunderkind. He leaned in.

Dear Bitch,

I wonder if it’s possible to extract the ingredients of age and status from love, distilling it to its purest form.

Is there a purest form? Maybe age is the oxygen that combines with the hydrogen of social standing to form the drinkable molecule—maybe the love we drank was no more than the sum of our private parts.

Maybe it doesn’t exist at all and the elemental analogy is elementally elementary. My childhood pastor told me when I first questioned God, “But you believe in Love even though you never see it, just by feeling it.”

Looking back, I think—“Good point!” If God Almighty doesn’t deserve my unfounded faith, why love? So thank you for showing me that love is the current myth—Zeus’ new chariot rolling over the clouds, prompting incorrect discernments of thunder, the eminent empirical mirage, the new deity for a scientific exposé—an energized biochemical reaction, the product of genetic variants that survived for reproductive value. A true agnostic must doubt not only God but the existence of supra-biochemical love.

So you’re leaving me. Have already left. How realist! Complexly challenging the primary-colored fairy tale endings, finding the beauty in grainy city light—the tumor that would have killed Majnun if a suicidal knife didn’t do it first. I’m for Majnun. I’m for a good story being an intentionally simple thing, without the condescending fellaheen stigmas of the word. I loved you like Majnun might have, a few of us are still out there, rendering vulgar the realist assumptions about complex and nuanced people being necessarily richer from their texture, and simple people being mere romanticist or patriotic fantasies. There is nothing necessarily quaint or simpleton about simplicity.

But McLean knew the vast majority of people aren’t simple, and truly simple people make for seemingly oversimplified representations (when consumed, he reflected, by complex, nuanced assholes like me). So he textured and layered his “meaningful conflict,” structured it and molded a pompous unreliable narrator. He left the vestiges of prehistoric art, of fairy tales and cave paintings that rebel through happy endings against reality itself, to pathetically directed chick flicks and action movies.

…my ancient love made fragile by its own rigidity. And I become another cliché hero who heroically ignores his own heroic nature to achieve a meaningful end.

Meanwhile, Winkowski’s first payment had been used to install an electric wall-mounted heater to the tub faucet (to hell with the building manager), and McLean was drawing himself a bath.

§

His hard-soled dress shoes echoed in the old building. His ankles hurt from working a double at the diner the day before but he’d decided to dress professionally for the occasion. There were no benches in the hallway and as he paced they ached with each reverberating step. He smiled to himself—such a healthy reminder that you are going to die: the aching whispers of your own wraith that you’re disintegrating while alive. Enough ankle pain and he could transcend—watch himself pace that hallway like watching a movie—laughing at the simple stakes his benign little character battled for, raged over, craved, despised.

Winkowski would kill him if he knew he was here but McLean couldn’t help it. He knew that teacher wouldn’t give him an A. Not because the paper didn’t deserve it (although, he reflected, it didn’t, because the student hadn’t written it) but because the teacher was an asshole. He had learned the equation from his tables: very rarely is there a table that will run you around and then tip you for it. Tables either run you around and tip shit—fifteen percent—are averagely polite and tip about eighteen to twenty-two, or are super polite and tip twenty-five or more. It’s not the consumer you work hardest for who rewards you—it’s the one you barely have to work for. This guy, he guessed, was a run-you-around fifteen-percenter. So they should expect a B-. Fine. That’s life. But being here he could go in and, as the student’s “tutor,” inquire as to why, hopefully sweet-talking some extra points towards an A- or an extra credit option.

Fifteen percent, he looked out the window on the university lawn. That dumb fucking kid. And he isn’t even the bad guy. We’re the bad guys. He’s the comic relief. Back to pacing. Lucky for us there’s no good guy. It’s some sardonic anti-romantic comedy.

The class poured into the hallway, Lori among them. Lori—who announced in her chubby movements that she hated her own body, who would have been the heighth of fertile beauty only a hundred years ago, and for hundreds of years before that, plump curves and blue eyes, the whole package now tragically dated and oversimplified as fat.

“Lori!”

She looked up, startled. “Uncle Bria—”

He snatched the paper from her hand.

D-.

Under his breath, in a quiet and professional tone matching his suit, he meditated aloud: “That little fuckface.”

The door opened and an Asian kid who was about thirty, the sleeves of his white collared shirt rolled up over tattooed arms, rushing out with a stack of papers in one hand, froze. “Dr. McLean!”

The nemesis had addressed him by name, had recognized him, but didn’t look familiar. Through a nervous smile, the kid went on: “It’s so good to meet you. I’m a critical fan of The Tumultuous Dessert.”

“Thanks.”

The gentle recedes of the kid’s hairline glistened as he told McLean he would love to exchange email addresses, maybe meet for lunch sometime.

“No thanks.”

The kid said he understood. Completely. That McLean must be a very busy man. “But good to meet you face to face at least. A true honor.”

§

When the echoes of McLean’s shoes down the empty hall died and the sidewalk began, he stopped and lit a cigarette. His anger at the kid’s urbane aggression molted from his guilt. And, starting the long walk home, he descended—past the grass and subterranean plumbing to the realm of poetry. Philosophy. And the teneral freedom of defeat.

This story first appeared in MAKE #8, “This Everyday.”

Caru Cardoc was raised in Chicago by a Welsh mother. He studied English at the University of Iowa, paying his way by, among other things, washing the pseudo-soups of ketchup, ice cream, and soda (concocted in playful ignorance by his less money-strapped classmates) from dirty plates in the dormitory cafeteria. He is currently an unapologetic waiter in the city of his youth. Caru’s work has been included in Storyglossia, Word Catalyst, and Jersey Devil Press.

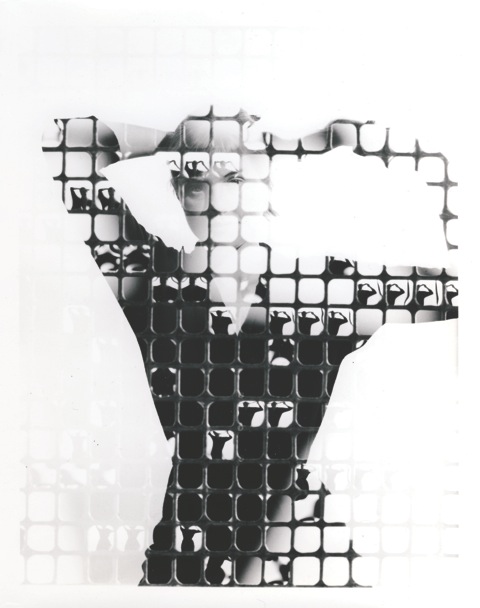

Image: Kenneth Josephson, “Girl Combing Hair,” Chicago, 1960, Silver Print.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig