by Alessandra Stamper

Before I tell you anything more about the boy and the girl, could you remind me of what I’ve told you already? Have I told you about the man with the tar beneath his feathers, and how the man’s black hat now hurts his head when he wears it? That hat, though a full ten gallons, is made of the softest, lightest felt I’ve ever brushed my fingers against, so that should tell you something. It should tell you how painful it is to carry those white feathers on his flesh, so painful that even a hat as light as a feather weighs heavily on his tender head. I’m not making excuses for him. I’m just saying there are things to be considered before coming to conclusions.

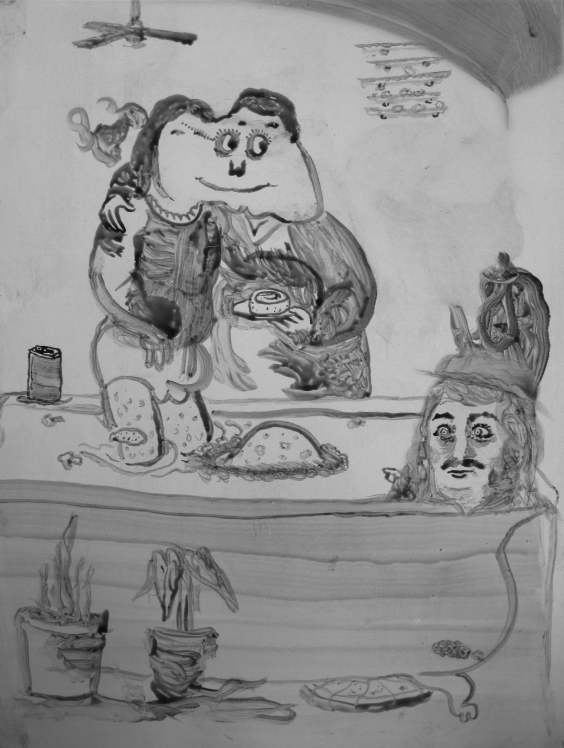

Did I tell you that the boy and the girl are in a bathtub? And when I tell you that, do you picture the children naked, even though they aren’t naked at all? And if you do picture them naked even when they aren’t naked, do you realize that makes you no better than the man in the hat? Nakedness, especially the nakedness of children, is morally objectionable in all circumstances. How does it feel to be judged for the terrible things you imagine? I bet it doesn’t feel good at all.

The boy wears the girl’s dress and the girl wears the boy’s suit. I’m kidding, of course, but I bet you enjoyed picturing that too. No, the boy wears what is normal for boys to wear and the girl wears what is normal for girls to wear, so these children absolutely do not deserve the awful consequences that befall them in this story, and if you have any sense at all, if you have an ounce of dignity or respect for yourself, you’ll stopper your ears while you still have a chance to be mistaken, while you still have a chance to hope for everything to turn out exactly like nothing ever really does in real life.

Are you still there? Of course you are. You’re gluttons for punishment.

They call the boy Teddy because he has big ears and thick brown hair (and his name is Theodore), and they call the girl Stitch (for reasons that will become clear in a moment). Teddy is a student at a school where rich parents abandon their boys to be taught esoteric equations and histories skewed for the purposes of promoting a national vanity. These boys often eventually trade their school uniforms for military ones, then eventually trade their military garb for business suits. But now, still only a teenage boy, Teddy always wears striped sweaters of cashmere, a tiny blue teddy bear sewn onto each pocket and handkerchief (a junior approximation of his father’s style—his father’s name is Leonard, his nickname Leo, and his pockets are adorned with little lions mid-stride). His mother does all the embroidery with all the spare time she has now that her son is away at boarding school. She wraps his sweaters and button-downs in butcher paper and twine, and takes them to the post office herself. She makes a day of it, this venture off the estate. She has afternoon tea in the back of an antique shop, and she browses for brittle sheets of vintage music that she’s been using to paper the walls of the piano parlor. But now that Teddy’s off at school, the piano’s never played. It makes no sense to pay the maid to dust seventeen rooms when only half so many are used in Teddy’s absence. If I sell the piano, she ponders as she riffles through a lackluster array of faded sheet music stacked in a washtub in the antique shop, then the maid couldn’t possibly expect full pay. And papering the walls in this manner is juvenile, tacky, she concludes, recalling her girlhood before she married well. She’d had an inclination to tape to her bedroom wall, above her headboard, pictures of movie stars torn from magazines.

Stitch, meanwhile, is a ward of Rothgutt’s, an institutional home for motherless girls. Teddy doesn’t know Stitch’s real name, and neither does she. She may have never had one, arriving as she did on the doorstep of the orphanage with not a stitch of clothing on beneath her scratchy blanket, no garment with her name sewn in.

So yes, that’s why the nuns named her Stitch, but years later, in her teens, her name came to fit even more exceptionally. And this late, dark afternoon I’m describing, this desperate nightmare shared between Teddy and his forbidden love, Stitch shows him her stitches. Teddy has never noticed them beneath her bangs until she begins to unstitch the stitches in a way that doesn’t seem obscene to him at all. The girl takes a needle from the pocket of her smock and threads the eye of it through a bit of the stitching that has come loose just above her left eyebrow, and she begins to unsew, undo, working the needle in and out of her flesh without the slightest flinch of pain. The skin of her forehead parts, curling, puckering like lips for a kiss. The girl leans forward, lifting her bangs with her left hand, and lifting the boy’s left hand with her right one. She points his pointer finger and brings his hand to the opening in her head.

Teddy loves Stitch and Stitch loves Teddy, but they can only see each other in secret, stealing off in the middle of each night to a rotting hotel on a vanished beach. The Grand Façade is all fallen cupolas and turrets, having housed vacationing dignitaries and socialites until the water of the lake shrunk to a puddle one apocalyptic season of drought. But there are still the remnants of elegance: stone mermaids frolicking with crumbling fins in a dry fountain, a crystal chandelier shaped like an octopus having long since crashed to the dancehall floor. Stepping through the hotel’s moldy corridors, Teddy and Stitch had felt like aquanauts visiting a ship sunk to the bottom of the sea. When Teddy stopped in the chapel to tickle out a tune on the piano’s grinning mouth of missing teeth, the echo and the discord, so muffled and ghostly, had the thump of music heard through waterlogged ears. In the bent, dusty rays of the setting sun, light reflected off some water somewhere and danced and waved across walls papered with a nautical print of yachts and lighthouses.

“The honeymoon suite,” Teddy said, gesturing through the door to a room mostly gone. Was he beckoning her toward her suicide, Stitch had wondered (but she wondered it without even a tinge of concern; actually, her pulse quickened with morbid delight over the romantic finality of such an invitation). The floor had fallen away, a heart-shaped bed far below, hanging from the rafters of the ceiling of the first floor, dangling, like in the ribcage of a giant wood skeleton. Teddy took Stitch’s hand and they tiptoed in a tandem live-wire act across the remaining wood planks to the bathroom, and to the tub, with its rusted faucets shaped like spitting seahorses.

Yes, they’d heard of the dangers of desolate places—especially with the man in the hat on the loose. But what seemed more urgently dangerous was to be too long apart. When you’re so young, and so in love, the only fear worth anything is the fear of love fading too soon.

Teddy knows that under normal circumstances he’d be punished if caught with his finger in an orphaned girl’s head—he’d likely get no cake with supper, but considering that it was the pink frosting of the angel food that had poisoned the Japanese triplets at school—did you know that getting sugar in your veins is fatal?—then supper without cake really didn’t seem like much of a punishment at all. Teddy is surprised to find that Stitch has no skull, and his finger slips easily into the live jellyfish that keeps her boneless head from collapsing in on itself. His knuckle rubs against more stitching when it reaches her brain.

“Surgical floss,” Stitch explains. “From when my real brain and my dream brain drifted apart. That was why I was crying myself awake every midnight.” Stitch’s mournful wail could not be contained by the nuns, not even with her windows shut and shuttered, and quilts piled atop her writhing body. Her crying had unsettled the villagers. They took a collection in order to fund a diagnosis and a treatment so they could finally sleep at night. The sister witches at the voodoo shop, however, took a more malignant approach, peddling devices and concoctions designed to sicken evil presences. For years, the witches had made a pretty penny off the paranoia of the lost lake, promoting the mythology of sea creatures taking human form and walking among us in lawless violation of our cosmic serenity.

“Did they do it?” Teddy asks. “The doctors? Did they reconnect?”

“Oh no, not at all,” Stitch says, sighing, although she knows she shouldn’t be such a sourpuss (although she knows such sourness makes her more tragically beautiful to a boy like Teddy). The floss had worked for a few days, and she’d had a few nights of blissful sleep. In her nightly terrors, stairs collapsed beneath her feet, but for a few days after the reconnection, the stairs became department-store escalators, shuttling her to the doll department.

The girl’s doctor hadn’t known what he was doing with the surgical floss because he wasn’t really a doctor. He’d been only pretending for the nuns. His was a sickness—a compulsive desire to help people, even if he couldn’t offer much help at all.

Before Teddy can assist Stitch with stitching her head all the way back shut, the bathtub’s claws unclench, and the tub rises from its perch and it rocks as it drifts up to bump the heads of the boy and the girl against the ceiling. But that’s not what breaks their little necks. They live a bit longer in this story. If you keep listening, you risk growing more attached to them. And what’s not to love? Those few days that that little girl had had no night terrors, she’d been the sweetest thing on two skinny legs. Her wrinkles had smoothed away, her hair had grown over the spots of her head she’d rubbed raw in her sleep. She looked like the cartoon in that machine that you stick a nickel in to watch, that you wind with a crank to make the cartoon girl get smacked with a frying pan. But it’s not as bad as it sounds, because only then does the cartoon girl get to see birds.

Oh, and the boy! I’ve always been partial to boys, especially the ones who are most like girls, and this one, this boy, he had eyelashes so long and so soft I used to secretly clip them with fingernail clippers as he slept, and I fashioned them into fake eyelashes that I wore to all the best parties, back when I used to get invited to them. The boy’s eyelashes looked so beautiful on me I couldn’t stop looking in the mirror, and for several wrenching weeks I thought I was falling in love with the boy, even though I knew it was just my lost youth I was missing. This is how fairy-tale witches are born, you know. They have, as their biology, our darkest moments. They’re so inhumane because we’ve invested them with our own human nature.

One good thing does happen to Teddy and Stitch in the tub. They stop bumping their heads against the ceiling. The ceiling turns into moonlight and they float past, the bathroom vanishing behind them, even the mirrors. They don’t fear the loss of the room because to them it seems the worst is over, but I guess that’s the way of the brain in crisis. It soothes itself with deception. How would we live with ourselves otherwise?

The bathtub sails past all the children the man in the hat killed this terrible summer, and although the children—rich and poor alike (the man in the hat had not discriminated in his blood thirst)—swim up to the tub with vigor, they are nonetheless lifeless corpses. Even the slutty twin teenyboppers who wear perfume they bought from a vending machine on the wall of a truck stop ladies room, even they can’t help the boy and the girl, despite the fact that they must’ve known everything worth knowing when they’d been alive. The twins’ pockets are full of rubbers they would never attach to a boy’s thing—they had just bought them at the truck stop to seem sophisticated. Those girls should never have snuck out, not even for one night.

“I always did like you the best of all,” Stitch tells every single ghost, one after the other, as they swim up like porpoises. Of course, the girl can’t have liked everyone best, but the lie doesn’t feel like a lie since the lie can comfort more than the truth can at this particular moment. The truth, at this moment, feels jagged like glass that has already cut to the bone. But lies, lies! Those come from the dream side of her unconnected brain. If you lived on that side all the time, then the real side of your brain would be the dream side, wouldn’t it? Then the fiction would be the truth, and the truth would be the fiction. But I’d advise you not to carry that moral too far, or you’ll damage your logic and become capable of things you don’t want to be capable of—just ask the man in the hat, which I know you won’t do, because you don’t think you and him have anything to say to each other.

The boy, whose eyelashes have grown back, flutters them at everyone within fluttering distance, and although I myself would’ve completely buckled under at the sight of it, no one that matters notices at all. Teddy, as if sensing the end of this story is near, gives the girl the cough drop he’s been secretly saving in his pocket for later, saving for when the girl looked away and he could sneak it into his mouth without explanation, and tuck it behind his teeth, and let it melt away numbing his tongue until the cough drop was a tragic sliver that cut his gums with its edges.

As if they’ve heard their own story before, Teddy and Stitch know what all the machinery ahead will do to them. They can’t stop the flow of the tub along the waves of the victims of the man in the hat, and they know their soft flesh will not inflict any damage on the cogs of the contraption that seems designed solely to do them in, deep down in the hotel’s furnace room. So they make peace with the machine’s intentions. They kiss each other, and memorize the feel of the softness of their lips and the wetness of their tongues so they can think of it later and bring it to mind when they need it. The whistling of the steam of the machine grows louder and louder, so loud that they don’t even realize that they are screaming with fright. If you want, it’s a happy ending, because they go to their deaths thinking they are silent and stoic and brave. Just before the cog catches the cuff of his pants, the boy thinks he is whispering. He thinks he whispers in the girl’s ear that things in the morning are never as bad as they seem in the middle of the night.

Timothy Schaffert is the author of five novels, most recently The Swan Gondola (Riverhead/Penguin). His work has been a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers pick, and an Oprah.com Book of the Week. He was also the editor of You Will Never See Any God: Stories by Ervin D. Krause.

Geoffrey Hamerlinck occasionally edits the obscuro comix newsletter, The White Buffalo Gazette. He occasionally teaches drawing and printmaking at St. Cloud State University, and Ox-Bow School of Art and Artists’ Residency. Occasionally he works at a grocery store and occasionally flips out at customers. Occasionally he draws, paints, prints, makes comics, animates, even makes clay sculptures. Most of the time he is not doing any of these things.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig