|

Now winter nights enlarge |

On the evening of the Groundhog’s Day snowstorm, I holed up in my third floor flat, whose 16-square-foot window looks north over neighborhood rooftops and church steeples. As the afternoon grayed, and the wind began to bang against the glass, and lightning turned the blizzard blue, the first stanza of Thomas Campion’s poem came to mind. It’s ominous, vaguely fantastic, and perfectly suited to a night watching that tremendous storm.

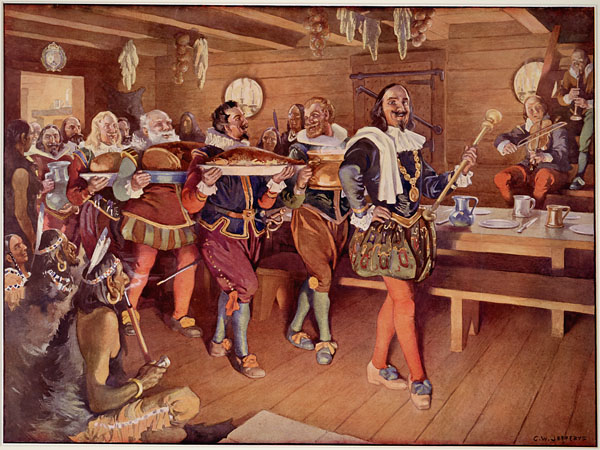

North America's first Social Club, the Order of Good Cheer-- founded as a way through the Canadian winter I looked up the rest of poem the next morning, and found that this quatrain followed the first: Let now the chimneys blaze Campion hints at an aspect of the winter season often overlooked by those Facebook posts from our gloating acquaintances in California and Florida. But how honest is he being with us, and are we being with ourselves? Does winter really come smiling with such a convivial face? On late afternoons in November, as I prepare to make my way from the office to the bus, we begin to marvel that the evening now ensues at such an early hour. As the sun begins to set behind a dirty cloth of cloud, I wonder if it had been really out at all, if the sky weren’t simply moving from pale grey to cobalt grey. The blackening trees remain staid throughout the afternoon and from my windows I join the leafless bowers in peering over the lonely, occasional pair of trousers that flap swiftly to the el, or bus, or car. It’s at times like these then that we ourselves feel becalmed and isolated, deserted by both our celestial deity and our companion city. |

In Watermark, his rumination on Venetian winters, Joseph Brodsky wrote that, “winter is an abstract season: it is low on colors, even in Italy, and big on the imperatives of cold and brief daylight.” The dwindling daylight does deliver us imperatives, but more interestingly, I think, is how demanding winter darkness drives us into a peculiar insanity. There are plenty of colors in our sunless winters, but they are often colors of our mind. We retreat into dreams, paranoia and delusions. Campion puts a romantic spin on nights spent drunk in the dark, but lonely people flush with vitality aren’t always as he suggests. Winter sends old men, weary from the sunless days, home to blunder across the kitchen table, spilling platters of food on the floor; it prods cocksure dudes to stomp proudly out of bars before stumbling shoulder-first into streetlamps and off the curb to burp out curses at passing cars; it entices the pale breasted, uxorious, and drunk-eyed to smirk and lift their sweat-scented knit tops in the bar back booth for some slobbering nitwit. As the winter comes in, as the days get squat, we become hermits of sorts, paunchy and harsh, panicked at the shortness of the days, stuck in our rooms, dug into books, chipping paint off the walls, cleaning and re-cleaning under the mattresses, packed in and restless, ready for hasty proclamations and irrational acts. The rest of the season we stay buried, living off what our memories and imaginations provide. During these winter hours, when we pile things around us, our homes become both harbor from the darkness and somehow a deep surreal pool filled with water both magic and plain. Our hibernal homes, our December apartments, become as Neruda called them, our “cosmic head of dreams… when all was moon or stone or darkness, when light was still unborn.” Even the cynic Machiavelli noted, with a Campion-esque romanticism, the surreal space that exists in our hermits’ harbor-homes in the winter: “When evening comes, I return home and go into my study. On the threshold I strip off my muddy, sweaty, workday clothes, and put on the robes of court and palace, and in this graver dress I enter the antique courts of the ancients and am welcomed by them, and there I taste the food that alone is mind, for which I was born. There I make bold to speak to them and ask the motives for their actions, and they, in their humanity, reply to me. And for the course of four hours I forget the world, remember no vexations, fear poverty no more, tremble no more at death: I pass into their world.” When the shoveled-up drifts that flank these days melt, when the grayscale sky is edited away, when that pattern of night, dun, night runs out, our panicked, lonely winter dreams will seem antirational. But when your only illumination is the dusty yellow light of kitchens that smell of twenty penned-in dinners, when the drippy, goofy drool-drivel of pissed-out tavern swivel-stool chatter is all the company you’ve got to sustain you for weeks on end, when the odd-heard songs played in dank basements set the melodrama for the unconscious, our dense dance rude inevitably ensues and can, within that reverie, be excused. Our waltz of curses, spit, rare randy moments, hopeless gestures, becomes comprehensible inside these illusions. And so our ridiculously exaggerated stage gestures seem to cohere entirely within winter’s dreamed drama. For the most part our world in winter is one of grey starkness, harshly real. And we flee from it when we can– usually into our homes and ourselves. We stir. We dream. We drink. We argue over nothing. We brood. We wish it weren’t so cold, but mostly so dark. This is important. As Frank O’Hara said, “it’s true that fresh air is good for the body, but what about the soul, that grows in darkness.” In the deepening months at the start of the year, the sky gets greyer, the north wind grows brisker, the moon rises somewhere unseen behind the clouds. |

|

These deep blizzards make our winter dreams communal, and thus humanize them. The sordid passages are deleted somehow and we are left only with wonder. Jerry Sullivan the wildlife columnist wrote in a 1984 issue of The Chicago Reader of the ice fishermen in Chicago’s harbors. Sullivan focused on the absurdity of the act: the harvested fish are tiny, and they are hibernating and so don’t fight much, and there is very little sport in awling out a hole at random to reach the unseen water. But ice fishing’s communal absurdity, Sullivan points out, it invites others into those dreams winter makes us harbor: “So you don’t catch many fish. And those you get are very small. And even the occasional big one is too cold to fight. And the winds howl across the open ice. But the air is certainly fresh. You can kibitz with your friends or talk to your daughter with very few interruptions from hungry fish. Your ostensible occupation is respectable. If anyone asks, you can say you are fishing. You don’t have to admit that you are standing around in the subzero windchill just to be sociable. “And you can stare at the skyline. If you are properly dressed, you can feel the cozy inexpressible joy of one who is warm in a cold place. And you can dream about how good it will be when the ice is gone.” The unforgiving Midwestern winter doesn’t bestow us “character”, as so often suggested by transplants to the coasts and the south. In fact, winter’s magic is that it erodes our character, our sense of self. Winter incubates our dreams, allows us to indulge in fantasies that arise from our minds and this stark, unforgiving, snow blind world. “One must have a mind of winter,” Wallace Stevens said, to behold “the junipers rough in the distant glitter of the January sun… and not to think of any misery in the sound of the wind… nothing himself, to behold the nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.” When you live here, when you are weaned on these winters, you don’t bemoan the despair of the winter, you find instead that communal dream– terrible and dark and fantastic. Snowbound, you revel in the dream; you allow your days to be written over by your lusting aspirations, your violent reverie, and your communal awe. With everyone, you are warmed by the distant glitter of the January sun, the glare of light off the downtown skyline. You can feel the cozy inexpressible joy of one who is warm in a cold place. |

|

| Back to The Silver-Colored Yesterday Home Page. |

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig